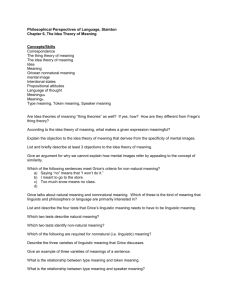

Grice on Meaning ()

advertisement

EINFÜHRUNG IN DIE THEORETISCHE PHILOSOPHIE: SPRACHPHILOSOPHIE Nathan Wildman nathan.wildman@uni-hamburg.de GRICE’S MEANING Or, meaning, (non) naturally – as God intended it to be What is a theory of meaning? Distinguishing two questions: I. The Meaning Question: For some sentence ‘S ’ in language L, what does ‘S ’ mean (in L)? II. The Foundational Question: What explains why ‘S ’ means what it does in L? Answers to I: Propositional theories assign to S a proposition as its meaning. (Russell, Frege) Verificationist theories say that to understand ‘S ’ in L is to know what empirical observations would confirm ‘S ’. (Logical Positivists, Ayer) Truth-conditional theories say that, to understand ‘S ’ in L is to know what it is for ‘S ’ to be true in L (i.e., to know the ‘truth condition’). (Quine, Davidson) But what about II? Grice’s answer: a speaker’s intentions fix the meanings of an expression! The project of reducing talk of meaning to speaker intentions (or other kinds of mental intentionality) is known as intention-based semantics. NATURAL & NON-NATURAL MEANING There are two kinds of meaning: Natural Meaning: This is the kind of meaning something has when it is a non-conventional sign for something. Non-Natural Meaning (meaningnn): This is the kind of meaning something has when it is a conventional sign for something. NATURAL & NON-NATURAL MEANING Some examples of Natural meaning : (a) Those spots on your face mean you have measles. Could be true only if the italicized sub-sentence is true, i.e. only if you really do have measles. (b) The recent budget means that we shall have a hard year. Could be true only if the italicized sub-sentence is true, i.e. only if, given our budget, next year will be difficult. NATURAL & NON-NATURAL MEANING Some examples of Meaningnn: (c) Those three rings on the bell (of the bus) mean that the bus is full. It could just as easily have been four rings! (d) The sentence ‘Snow is white’ means that snow is white. We might have used that string of symbols to have meant something else. NATURAL & NON-NATURAL MEANING Note: It isn’t quite correct to draw the distinction in terms of conventional/non-conventional signs Words can have meaningnn but not be signs. Some gestures can have meaningnn but not be conventional. The recent budget has a natural meaning but is not a sign. NATURAL & NON-NATURAL MEANING Natural Meaning: Success: ‘x means that p’ entails p (given x) Agent Independent: ‘x meant that p’ doesn’t entail ‘Someone meant that p by x’. Fact-Involving: ‘x meant that p’ can be restated as a sentence of the form ‘The fact that . . . meant . . . ’. Meaningnn : Lacks these characteristics NATURAL & NON-NATURAL MEANING Rule of thumb: It is consistent with something's having a particular non-natural meaning that what it non-naturally means is false; It is not consistent with something's having a particular natural meaning that what it naturally means is false. That is, meaningnn defies Success ANALYSING MEANINGNN In any case, the kind of meaning distinctive of linguistic expressions is non-natural meaning A quick distinction we’ll come back to later Speaker meaningnn : Speaker S means something by x. Mike means something by ‘Snow is white’ Sentence meaningnn : Speaker S means by x that Φ Mike means by ‘Snow is white’ that snow is white ANALYSING MEANINGNN Causal Analysis: For x to meannn something, x must have (roughly) a tendency to produce in an audience some attitude and a tendency, in the case of a speaker, to be produced by that attitude (dependent on an ‘elaborate process of conditioning attending the use of the sign in communication’). Grice finds two things wrong with the causal account: (1) Omits intention – what must be specified is not the effect produced, but the effect the speaker intends to produce. (2) Ignores what a particular speaker may mean on a particular occasion. ANALYSING MEANINGNN Counterexample 1. Putting on a tail coat satisfies Steven’s causal conditions by producing in an audience the attitude that one is going to a dance and by being produced by an attitude in the tail coat-wearer that he is going to a dance; but the wearer meant nothing by wearing the tail coat. Counterexample 2. To say ‘Jones is an athlete’ tends to make someone believe that it is true that ‘Jones is tall’. But the latter is not part of what is meant by the former. We cannot explain this away by invoking linguistic rules, since that is just to invoke meaningnn. ANALYSING MEANINGNN 1st proposal. S meantnn by x that P iff (1) S uttered x intending for his audience to form the belief that P. Problem: Handkerchief counterexample - If S leaves B’s handkerchief at the scene of the crime with the intention of getting the detective to believe that B did it, then my leaving the handkerchief meantnn that B was the murderer. But that’s just wrong! Solution: add clause about recognizing intention! ANALYSING MEANINGNN 2nd proposal. S meantnn by x that P iff (1) (2) S uttered x intending for his audience to form the belief that P; and S also intended that his audience recognize that’s what he intended to do. Problems: St. John: Herod didn’t meannn that St. John was dead when he brought his head to Salome Child: The child didn’t meannn that it was sick when it showed how pale she was Broken China: I didn’t meannn that daughter broke the china, when I left it out Solution: invoke difference between showing & drawing a picture ANALYSING MEANINGNN 3rd proposal. S meantnn by x that P iff (1) (2) (3) S uttered x intending for his audience to form the belief that P; and S also intended that his audience recognize that’s what he intended to do; and S also intended that his audience form the belief that P at least partly because they recognize that’s what he intended to do. Slightly shortened: A uttered x with the intention of inducing a belief by means of the recognition of this intention. MINOR OBJECTIONS? Two Quick Objections: (1) This requires an audience – can’t I soliloquize? (2) I don’t always intend to produce any beliefs in you when I utter meaningful sentences – I might tell you a proof for 2+2=4. SUMMING UP 1) Grice suggests that x meantnn something is (roughly) equivalent to somebody meantnn something by x. That takes care of Speaker meaning! 1) Finally, x meansnn that so-and-so is (roughly) equivalent to what people generally intend to meannn by uttering x. That takes care of Sentence meaning! SUMMING UP Meaningnn is to be analyzed in terms of reflexive intentions—i.e., the intention to induce a psychological state in a hearer by means of a recognition of that very intention. If Grice is right, speaker’s meaning (what a speaker intends to communicate) is a more fundamental notion than sentence meaning – sentences mean what they do because of what speakers intend to communicate by means of them; rather than, speakers mean what they do because of what the sentences they use mean. SUMMING UP As Grice later puts it, we can distinguish between: Relativized meaning, the explication of which essentially involves reference to word users or communicators Nonrelativized meaning, where no such reference is required Nonrelativized meaning is the secondary notion, capable of being reduced to, or analyzed in terms of, relativized meaning; and no corresponding analysis or reduction in the other direction is possible SOME PROBLEMS? A red traffic light meansnn stop; but who meantnn stop? Sometimes, the intended effect must be under the audience’s control. Speakers can mean anything by anything, but sentences are constrained. Some sentences almost always are used to mean something other than their literal meaning. Most sentences are never uttered at all, but are still meaningful; novel sentences have no pre-established conventions for use, and yet we still instantly find them meaningful. SOME PROBLEMS? – SEARLE‘S OBJECTION Suppose that I am an American soldier in WW II and that I am captured by Italian troops. And suppose also that I wish to get these troops to believe that I am a German officer in order to get them to release me. What I would like to do is to tell them in German or Italian that I am a German officer. But let us suppose I don’t know enough German or Italian to do that. So I … put on a show of telling them that I am a German officer by reciting those few bits of German that I know, trusting that they don’t know enough German to see through my plan. Let us suppose I know only one line of German, which I remember from a poem I had to memorize in a high school German course. Therefore I, a captured American, address my Italian captors with the following sentence: “Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühen?” SOME PROBLEMS? – SEARLE‘S OBJECTION Searle claims that the three clauses of Grice’s account of meaning are satisfied: I intend to produce a certain effect in them, namely, the effect of (i) believing that I am a German officer; and I intend to produce this effect (iii) by means of their (ii) recognition of my intention. But when I say “Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühen?” I don’t meannn ‘I’m a German Officer’ – rather, … because what the words mean is, “Knowest thou the land where the lemon trees bloom?” … Meaning is more than a matter of intention, it is also a matter of convention. [Searle, “What is a Speech Act?”] NEXT WEEK J. Austin’s ‘Performative Utterances’ A scan will be uploaded this evening We’ll discuss the practice exam a bit, but mostly just work though Austin (though I’m happy to answer any questions people have)