A case study for Tele-Immersion communication

applications: From 3D capturing to rendering

Dimitrios Alexiadis, Alexandros Doumanoglou, Dimitrios Zarpalas, Petros Daras

Information Technologies Institute, Centre for Research and Technology - Hellas

Introduction – Problem Definition

Tele-Immersion (TI) technology aims to enable

geographically-distributed users to communicate

and interact inside a shared virtual world, as if they

were physically there [1].

Key technology aspects:

1) Capturing and reconstruction of (3D) data,

2) (3D) data compression and transmission,

3) Free-view-point (FVP) rendering

Substantial factors for user’s immersion:

1) Quality of (3D) generated and presented content,

2) Data exchange rates between remote sites,

3) Wide navigation range (full 360o 3D coverage)

3D Data representations [2]:

a) (Multi-view) Image-based modeling,

b) (Multi-view) Video+Depth,

c) 3D geometry-based representations

Contribution: We propose and study in detail a 3D

geometry representation-based TI pipeline, as a

reference for people working in the field.

The reasons for selecting 3D geometry-based

representations are: (a) Straightforward realization

of scene structuring and navigation functionalities

(e.g. collision detection); b) Wide range of FVP

coverage with relatively few cameras; c) Less

computational and network load for multi-party

systems; d) Potential benefit from the capabilities of

future rendering systems (holography-like).

Related work: [1] Multiple stereo rigs and view

synthesis at the receiver side; [3] Multiple Kinects,

but without studying compression/transmission;

[4]: Multiple Kinects, but compression is for the

specific reconstruction method[5]; [6]: Based on

image representations.

Tele-Immersion Platform

Systems overview

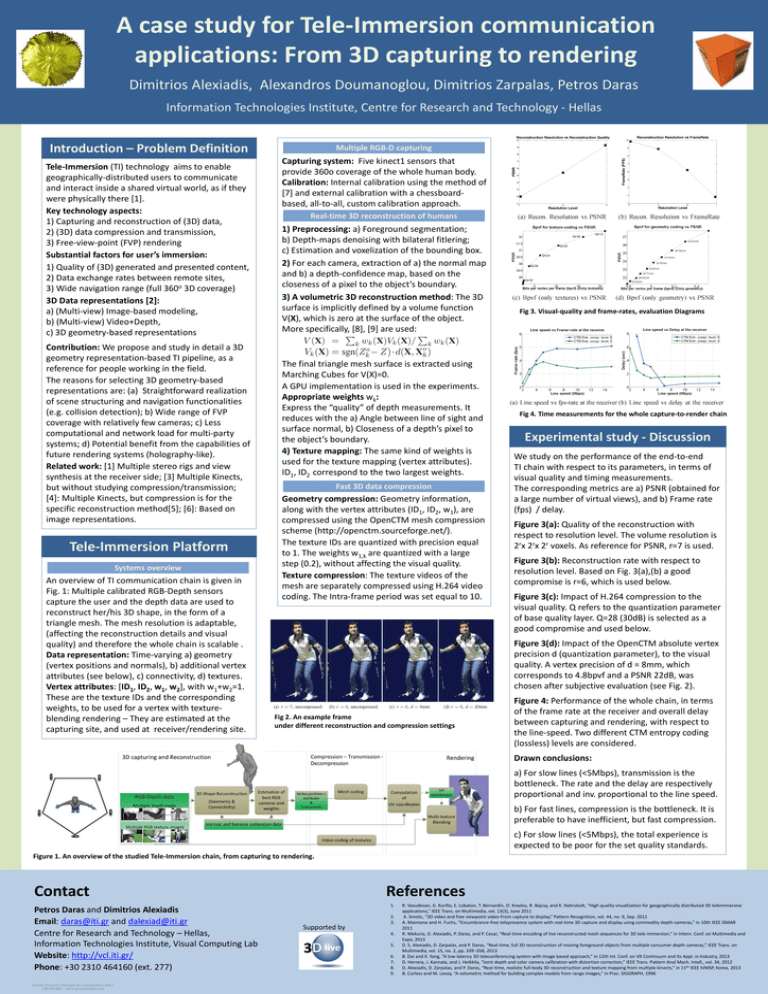

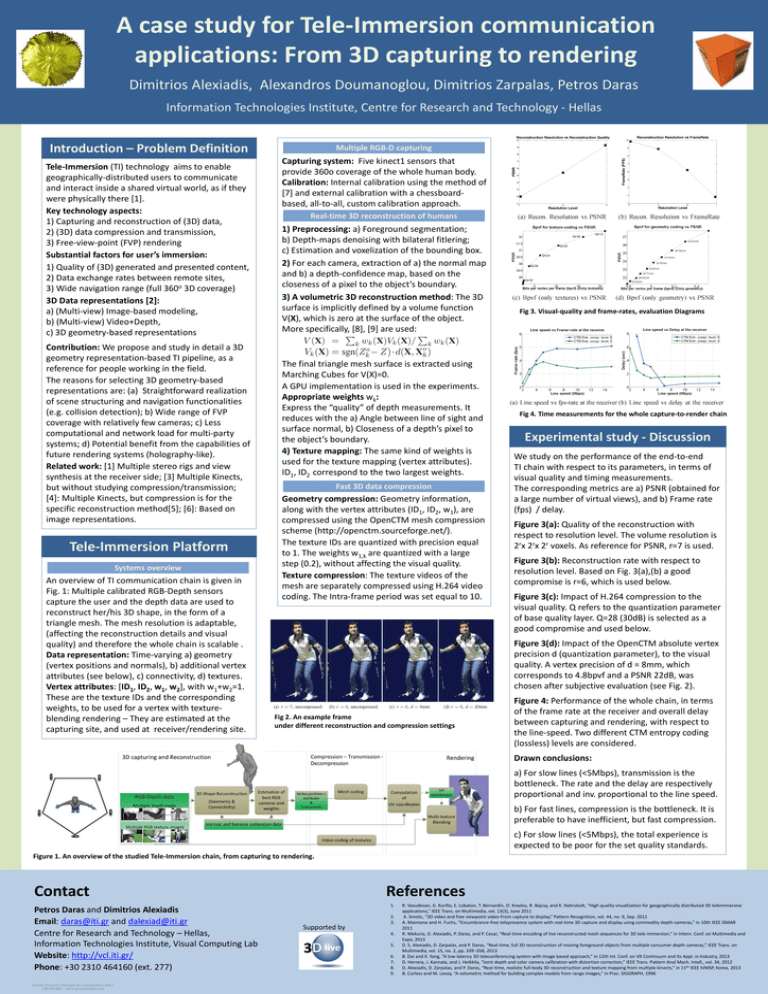

An overview of TI communication chain is given in

Fig. 1: Multiple calibrated RGB-Depth sensors

capture the user and the depth data are used to

reconstruct her/his 3D shape, in the form of a

triangle mesh. The mesh resolution is adaptable,

(affecting the reconstruction details and visual

quality) and therefore the whole chain is scalable .

Data representation: Time-varying a) geometry

(vertex positions and normals), b) additional vertex

attributes (see below), c) connectivity, d) textures.

Vertex attributes: [ID1, ID2, w1, w2], with w1+w2=1.

These are the texture IDs and the corresponding

weights, to be used for a vertex with textureblending rendering – They are estimated at the

capturing site, and used at receiver/rendering site.

Multiple RGB-D capturing

Capturing system: Five kinect1 sensors that

provide 360o coverage of the whole human body.

Calibration: Internal calibration using the method of

[7] and external calibration with a chessboardbased, all-to-all, custom calibration approach.

Real-time 3D reconstruction of humans

1) Preprocessing: a) Foreground segmentation;

b) Depth-maps denoising with bilateral fitlering;

c) Estimation and voxelization of the bounding box.

2) For each camera, extraction of a) the normal map

and b) a depth-confidence map, based on the

closeness of a pixel to the object’s boundary.

3) A volumetric 3D reconstruction method: The 3D

surface is implicitly defined by a volume function

V(X), which is zero at the surface of the object.

More specifically, [8], [9] are used:

The final triangle mesh surface is extracted using

Marching Cubes for V(X)=0.

A GPU implementation is used in the experiments.

Appropriate weights wk:

Express the “quality” of depth measurements. It

reduces with the a) Angle between line of sight and

surface normal, b) Closeness of a depth’s pixel to

the object’s boundary.

4) Texture mapping: The same kind of weights is

used for the texture mapping (vertex attributes).

ID1, ID2 correspond to the two largest weights.

Fast 3D data compression

Geometry compression: Geometry information,

along with the vertex attributes (ID1, ID2, w1), are

compressed using the OpenCTM mesh compression

scheme (http://openctm.sourceforge.net/).

The texture IDs are quantized with precision equal

to 1. The weights w1,k are quantized with a large

step (0.2), without affecting the visual quality.

Texture compression: The texture videos of the

mesh are separately compressed using H.264 video

coding. The Intra-frame period was set equal to 10.

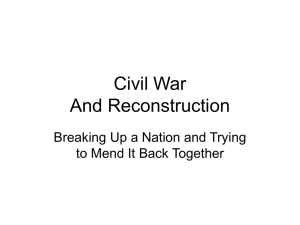

Fig 3. Visual-quality and frame-rates, evaluation Diagrams

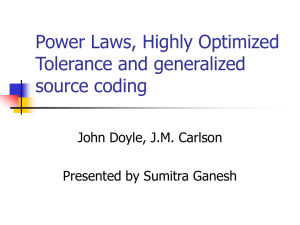

Fig 4. Time measurements for the whole capture-to-render chain

Experimental study - Discussion

We study on the performance of the end-to-end

TI chain with respect to its parameters, in terms of

visual quality and timing measurements.

The corresponding metrics are a) PSNR (obtained for

a large number of virtual views), and b) Frame rate

(fps) / delay.

Figure 3(a): Quality of the reconstruction with

respect to resolution level. The volume resolution is

2rx 2rx 2r voxels. As reference for PSNR, r=7 is used.

Figure 3(b): Reconstruction rate with respect to

resolution level. Based on Fig. 3(a),(b) a good

compromise is r=6, which is used below.

Figure 3(c): Impact of H.264 compression to the

visual quality. Q refers to the quantization parameter

of base quality layer. Q=28 (30dB) is selected as a

good compromise and used below.

Figure 3(d): Impact of the OpenCTM absolute vertex

precision d (quantization parameter), to the visual

quality. A vertex precision of d = 8mm, which

corresponds to 4.8bpvf and a PSNR 22dB, was

chosen after subjective evaluation (see Fig. 2).

Fig 2. An example frame

under different reconstruction and compression settings

Figure 4: Performance of the whole chain, in terms

of the frame rate at the receiver and overall delay

between capturing and rendering, with respect to

the line-speed. Two different CTM entropy coding

(lossless) levels are considered.

Drawn conclusions:

a) For slow lines (<5Mbps), transmission is the

bottleneck. The rate and the delay are respectively

proportional and inv. proportional to the line speed.

b) For fast lines, compression is the bottleneck. It is

preferable to have inefficient, but fast compression.

c) For slow lines (<5Mbps), the total experience is

expected to be poor for the set quality standards.

Figure 1. An overview of the studied Tele-Immersion chain, from capturing to rendering.

Contact

Petros Daras and Dimitrios Alexiadis

Email: daras@iti.gr and dalexiad@iti.gr

Centre for Research and Technology – Hellas,

Information Technologies Institute, Visual Computing Lab

Website: http://vcl.iti.gr/

Phone: +30 2310 464160 (ext. 277)

References

1.

Supported by

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

R. Vasudevan, G. Kurillo, E. Lobaton, T. Bernardin, O. Kreylos, R. Bajcsy, and K. Nahrstedt, “High quality visualization for geographically distributed 3D teleimmersive

applications,” IEEE Trans. on Multimedia, vol. 13(3), June 2011

A. Smolic, “3D video and free viewpoint video-From capture to display,” Pattern Recognition, vol. 44, no. 9, Sep. 2011

A. Maimone and H. Fuchs, “Encumbrance-free telepresence system with real-time 3D capture and display using commodity depth cameras,” in 10th IEEE ISMAR

2011

R. Mekuria, D. Alexiadis, P. Daras, and P. Cesar, “Real-time encoding of live reconstructed mesh sequences for 3D tele-immersion,” in Intern. Conf. on Multimedia and

Expo, 2013

D. S. Alexiadis, D. Zarpalas, and P. Daras, “Real-time, full 3D reconstruction of moving foreground objects from multiple consumer depth cameras,” IEEE Trans. on

Multimedia, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 339–358, 2013

B. Dai and X. Yang, “A low-latency 3D teleconferencing system with image based approach,” in 12th Int. Conf. on VR Continuum and Its Appl. in Industry, 2013

D. Herrera, J. Kannala, and J. Heikkila, “Joint depth and color camera calibration with distortion correction,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal Mach. Intell., vol. 34, 2012

D. Alexiadis, D. Zarpalas, and P. Daras, “Real-time, realistic full-body 3D reconstruction and texture mapping from multiple kinects,” in 11th IEEE IVMSP, Korea, 2013

B. Curless and M. Levoy, “A volumetric method for building complex models from range images,” in Proc. SIGGRAPH, 1996