The Market for Sports Broadcast Rights

advertisement

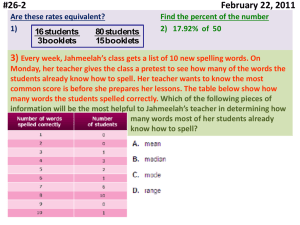

The Market for Sports Broadcast Rights 1 Here I present a diagram from the text in a slightly different way than the author. Media providers who broadcast games and broadcast advertising during the game. Sell rights to games Sports Teams and Leagues Get paid Rights Fees So, teams and leagues sell games to TV and Radio (and now even internet sources) and these media providers sell ad time to people who want to sell a product. Sell rights to Ad Slots (Time slots during game.) Get paid Slot Fees Organizations who want to buy advertising time – Advertisers 2 Advertising When firms buy advertising there could be an impact on 1) Folks who have not bought before – new buyers – start-up consumers, and 2) Existing customers. The author points out that there is unclear evidence that advertising leads to start-up consumption. Advertising may create brand loyalty by keeping existing customers informed about the product and any updates that occur. Note that the target demographic group is the group most likely to care about the product. 3 Advertising Advertising reach refers to how many of the intended demographic group see the ad. A “rating point” in TV means about 954,000 viewing homes. Tables 3.1 through 3.5 show different aspects of advertising. Some of this is that football generates most ad revenue and car and beer companies buy the most air time. 4 Broadcast Rights In the US it is usually the case that the national broadcast rights are handled by the league and individual teams handle local broadcast rights. The broadcast rights are typically sold in an auction setting where different media providers submit bids to be reviewed by team or league. The rights to broadcast might be for several years. For the TV and Radio companies, buying the right to broadcast games is an expense. Why do this? The quick answer is then revenues can be generated from selling ad slots during the game. Good economics would suggest if ad sales are more than expense for rights, then money can be made! 5 MR and MRP In economics terms like marginal revenue and marginal revenue product are used. Marginal revenue is used when the concept is about how the selling of an additional unit of output changes total revenue. Marginal revenue product is used when the concept is about how the “hiring” an additional unit of an input will change total revenue. (Note that both selling more output and hiring more inputs have costs, but in MR and MRP we focus on just the revenue side.) 6 Marginal Revenue Product of Broadcast Rights Media providers have as an output their TV shows. Broadcast rights are an input to be bought. The MRP of broadcast rights include the revenue from the sale of ad slots. But there is more to the MRP concept here. The author says there are spillover values to be had as well and these should be considered part of the MRP of broadcast rights. These include 1) The value of the network airing ads for its other shows during the game, 2) The sequencing value that occurs when folks who watch the game get hooked on the network and watch shows before the game and shows after the game, and 3) The fact that local affiliates of the national station get to sell 7 local ad slots and generate revenue. The Winner’s Curse The value to airing games to the media providers is the slot fees and spillover value. The cost is the auction bid (which turns out to be what the winner pays in get the broadcast rights. The value of having the broadcast rights is an uncertain future amount. The bid has to be made in advance. When you consider that several bidders will be involved it might be the case that the “average” bid will reflect the true value of broadcast rights, the winning bid would be above the true value. The curse is then the idea that the media provider who wins the bid has then paid too much. 8 Media provider buys and owns sports team There is an old rule of thumb in economics about firms and it goes something like this: Do something yourself as a firm when it can be done more profitably inside the firm than buying if from another. Some firms, for example, do the payroll inside the firm, while others find it more profitable to have an outside group do this. Potential gain to a media provider from owning a team instead of just buying right: 1) Gain local broadcast rights (the national broadcast rights don’t change in value just because media provider owns them), 2) Production efficiency may occur, 3) Possible tax efficiencies may result, and 4) Owning the team can be fun! The downsides to having media owned teams may include: 1) Media owned teams could have more money to buy talent and thus competitive imbalance on the playing field, and fans might not like “absentee” media owner because there is no one to complain to or plead to for better 9 team. Strategy Why would a beer company, for example, buy a slot of time on TV during a game? Of course it is thought the ad time will generate more sales – ad time has a marginal revenue product. A basic rule to follow: buy more ad time as long as the marginal revenue product is at least as great as the cost of the ad time. The basic rule here is fine, but there is an added element. This added element is that the outcome of ones own decision is not only influenced by their own action, but by the action of others. A non-economic example would be the game rock, paper, scissors. You winning depend not only on what you do, but also what the other player does. If Miller Beer thinks about buying ad time its impact will also depend on how much Bud Beer buys ad time. In this type of situation econ folks turn to Game Theory as a way to understand how firms might act. 10 Strategy Here is a story. Say Bud and Miller each are considering buying ad time during the next “super” game. The idea is they might get new customers and keep their product on the mind of their existing customers. Now, if neither buys ad time there is no expense and likely no real change in customer base. If both buy ad time it is likely their impacts cancel out and they are really just buying ad time to no affect. But, if one buys ad time and the other does not, then the buyer will gain market share and the non-buyer will lose out. In a situation such as this we turn to game theory in economics. 11 Game Theory Here we study a method for thinking about oligopoly situations. As we consider some terminology, we will see the simultaneous move, one shot game. 12 Simultaneous Move, One Shot Games We will again assume there are only two decision makers. For now we assume both have to make their decisions at the same time. This is a simultaneous move game. The main point about a simultaneous move game is that although I may know all the information about what the other guy might do, I do not actually see what is done before I do my thing. Games could be sequential, where one player follows the other. Some games have only one decision by each player involved. Other games involve repeated rounds of play. Here we focus on the one shot games. 13 Normal Form In the normal form of a game, information about the options of each player is presented in a matrix. The “row” player’s options are described in each row and the payoff is the first number in each cell. The “column” player’s options are described in each column and the payoff is the second number in each cell. Since we have a simultaneous move game each player will choose its options without knowing what the other player will choose. But the choice of the other player may be anticipated. Let’s check out an example on the next few screens. 14 Row Player up down Column player left a, A b, B right c, C d, D Let’s make sure we understand this table. Here we have two players: the Row Player and the Column Player (Miller and Bud, if you want). This is a generic game for now and all the Row Player can do is choose up or down (in rock, scissors, paper you can choose one of the three, but for the Row Player here the choice is up or down.) The Column Player can only choose left of right. Now, let’s say the row player picks up and the column player picks left. 15 Row Player up down Column player left a, A b, B right c, C d, D Now, let’s say the row player picks up and the column player picks left just as an example to see what each would get. If the game ended at up, left, the row player would get “a” and the column player would get “A.” Note all these letters usually are dollar amounts for us and can be negative amounts. But, sometimes the letters represent other concepts besides dollars. As an example the numbers could represent jail time. 16 Row Player up down Column player left a, A b, B right c, C d, D If the game ended at down, right, the row player would get “d” and the column player would get “D.” Caution: If as ROW Player you pick down thinking you get “b” remember that what you get is also influenced by Column Player. So, you could actually get “d” if the Column Player picks right. Next we want to think about how each player should decide what strategy to pick. 17 Row player should think this way: (As the row player) I do not know what the column player will do. But, I can look at each option of the column player, one strategy at a time. If the column player picks left my choices are up a down b As the row player I would pick the option that has the highest value: pick up if a > b, or pick down if a < b. If the column player picks right my choices are up c down d As the row player I would pick the option that has the highest value: pick up if c > d, or pick down if c < d. 18 For the row player the choice of strategy is up or down. A strategy is called a dominant strategy for a player if it has a higher payoff no matter what the other player chooses. So, up would be a dominant strategy for the row player if both a > b and c > d. Down would be a dominant strategy for the row player if both a < b and c < d. 19 Example Row Player up down column player left 10, 20 -10, 7 right 15, 8 10, 10 The row player will think in the following way(look at each column). If column man picks left I can have 10 if I go up and –10 if I go down. So I will go up. If column man goes right I can have 15 if I go up and 10 if go down. So I will go up. In this example the row player sees it is best to go up no matter what the column player is doing. In this sense we say “up” is a dominant strategy for the row player. 20 Example Row Player up down column player left 10, 20 -10, 7 right 15, 8 10, 10 This is the same slide as before, but I show in each column what the ROW player will look at. If the highest value in each column is in the same row – the person has a dominant strategy. Again, up is a dominant strategy here for the row player. 21 Column player should think this way: (As the column player) I do not know what the row player will do. But, I can look at each option of the row player, one strategy at a time. If the row player picks up my choices are left right A C As the column player I would pick the option that has the highest value: pick left if A > C, or pick right if A < C. If the row player picks down my choices are left right B D As the column player I would pick the option that has the highest value: pick left if B > D, or pick right if B < D. 22 For the column player the choice of strategy is left or right. A strategy is called a dominant strategy for a player if it has a higher payoff no matter what the other player chooses. So, left would be a dominant strategy for the column player if both A > C and B > D. Right would be a dominant strategy for the column player if both A < C and B < D. 23 Example Row Player up down column player left 10, 20 -10, 7 right 15, 8 10, 10 The column player will think in the following way(look at each row). If row man picks up I can have 20 if I go left and 8 if I go right. So I will go left. If row man goes down I can have 7 if I go left and 10 if go right. So I will go right. In this example the column player does not have a dominant strategy. What to do? If the other player has a dominant strategy, assume he will play it and then do the best you can. Column player should go left. 24 Example Row Player up down column player left 10, 20 -10, 7 right 15, 8 10, 10 This is the same slide as before, but the column player looks at his possibilities in each row. 25 Nash Equilibrium A set of choices by the players would be considered a Nash equilibrium if each player would NOT want to change their choice given the choice of the other player. The choices up and left represents a Nash equilibrium because neither would choose to change given the choice of the other. The row player says – if the column player will be at left, then it is best for me to stay at up. The column player says - if the row player will be at up, then it is best for me to stay at left. 26 Let’s pick a different cell than up, left to see why another cell might not be a Nash equilibrium. Let’s look at up, right. The row player says - if the column player is at right then I want to stay at up (Nash Equilibrium may still be in the running). The column player says – if the row player is up, then I want to change from right to left. Because the column player wants to change, the cell considered is not a Nash Equilibrium. Note: You look for dominant strategies before the game is played and you see if you have a Nash equilibrium after the game is played. 27 Applications Here we look at several applications. We will see a classic example of a dilemma that can arise in such games. 28 Pricing Example Row Player low price high price column player low price high price 0, 0 50, -10 -10, 50 10, 10 The numbers in the matrix represent profit. The row player has a dominant strategy of a low price (0 is better than -10 and 50 is better than 10) and the column player has a dominant strategy of a low price as well (similar numbers). And, low low is a Nash equilibrium. A dilemma that arises here is that both could be better off if they both went with a high price. 29 Prisoner Dilemma Games The game we just saw has the characteristic that has come to be known as the prisoners’ dilemma. When the players act separately (competitively) the outcome is worse than if they cooperated. 30 Don’t be taken advantage of In the pricing example each might be tempted to get together and both charge the high price and both do better than the low price strategy. The problem of the high, high solution is that it is not a Nash equilibrium and thus each would have the incentive to change to the low price strategy. Your stockholders would not want you to be taken advantage of by a double crosser. Don’t collude here, for it is not likely to pay off. Let’s see why. Say you are the row player and you agree (illegally) to set prices high with the column player. After you finish the meeting you will note 1) if you as the row player see the column stay at a high price the it is better for you to have a low price (this is part of why high, high is not a Nash equilibrium), and 2) perhaps more importantly you will note the column player also has the incentive to switch to low (this is the other part of high, high not being a Nash equilibrium). So, if you stay at high you will look bad! 31 Advertising Example back on slide 11 Firm 1 increase ad buying don’t buy firm 2 Increase ad buy $10, $10 $8, $17 Don’t buy $17, $8 $15, $15 Firm 1 has a dominant strategy of increasing ad buying ($10 million is better than $8 and $17 is better than $15) and firm 2 has a dominant strategy of a increasing ad buying as well (similar numbers). So, both players will do the dominant strategy of increasing ad buying and this solution is a Nash equilibrium. A dilemma –an advertising dilemma - that arises here is that both could be better off if they both went with not buying the ads. But, neither wants to be taken advantage of and the advertising escalation occurs. 32 Tacit Cooperation Each firm here is thought to understand the situation of noncooperation and a resulting dilemma. A way to get around the dilemma is to recognize that often the situation plays out many times. Because of this firms can try a pattern of action. For example firm 1 might not advertise one time and let the other get the ad, but then the next time it would do the advertising. Each firm would see they could trade off each time and continue to follow this pattern as long as the other follows the pattern as well. If each buys ads all the time the payoff is $10 each period. But if each buys ads every other time (and opposite of each other) then the pattern or payoffs will be $8, $17, $8, $17,…. 33 Outside Intervention Another way around the dilemma is to perhaps have an outside intervention in the form of a government ban. If the government can be convinced, a ban on ads would help the firms get out of the advertising dilemma. BUT, let’s recognize this outside intervention could be a problem as well. New companies who want to get into the market would not have the advertising to introduce its product to the buying public. This might mean we have a lack of entry of new firms in the market. You and I know that sometimes new firms bring bettor or more interesting products. 34 Sponsorship as Advertising Many companies that regularly advertise their products are also now buying naming rights on stadiums in team sports and also sponsor events in sports like golf. These sponsorships happen for the same reasons as we saw before, namely, buy sponsorship when it ads to the bottom line! For some teams the money from these naming rights adds significant cash to the team. 35