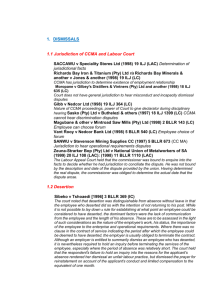

section 189a(19)

SASLAW 15

TH

ANNUAL CONFERENCE

SUBSTANTIVE FAIRNESS

SECTION 189A(19)

PRESENTED BY

PETER LE ROUX

Director

Brink Cohen le Roux Inc.

BCLR Place, 85 Central Street

Houghton, Johannesburg

Tel: (011) 242 8000

Fax: (011) 242 8001 e-mail: pleroux@bclr.com

1

1

THE ORIGIN OF SECTION 189A

To address the alleged inability/unwillingness of the Courts to interrogate the substantive fairness of operational requirement dismissals:

• The granting of a right to strike to challenge substantive unfairness.

To address the alleged inadequacy of consultation process:

• The introduction of a facilitation process.

• Requirement to engage in a meaningful consensus-seeking process.

2

2

SECTION 189A

• Only applies to “mass dismissals” or “large scale” retrenchments.

• It only applies if an employer has at least 50 employees and envisages dismissing a specified number of employees, depending on the size of the workforce.

• The result is a lengthy and complex section that has been the subject of extensive litigation and which would apply to a large number of retrenchments.

3

3

SECTION 189A(19)

“ The Labour Court must find that the employee was dismissed for a fair reason if -

(a) The dismissal was to give effect to a requirement based on the employer’s economic, technological, structural or similar needs;

(b) The dismissal was operationally justifiable on rational grounds;

(c) There was a proper consideration of alternatives; and

(d) Selection criteria were fair and objective .

”

4

4

THE PURPOSE OF SECTION 189A(19)

Introduced at the insistence of employers in order to create some certainty as to the test for fairness.

5

5

THREE ELEMENTS OF SUBSTANTIVE FAIRNESS

• Was the reason for dismissal a genuine operational requirement or merely a sham?

• Was it fair to dismiss for this operational requirement?

• The fairness of the selection criteria.

6

6

A GENUINE NEED OR A SHAM?

See for example Morestêr Bande (Pty) Ltd v National Union of

Metalworkers of SA & Another (1990) 11 ILJ 687 (LAC); Simelane &

Others v Audell Metal Products (Pty) Ltd (1987) 8 ILJ 438 (LC); SA

Mutual Life Assurance Society v Insurance & Banking Staff Association

& Others [2001] 9 BLLR 1045 (LAC) and NUMSA and Others v Genlux

Lighting (Pty) Ltd [2009] 3 BLLR 245 (LC).

7

7

FAIRNESS OF THE OPERATIONAL REQUIREMENT

DISMISSAL

The difficult issue – to what extent should the Court “second-guess” managerial decisions on the “big issues”.

8

8

ASSESSING FAIRNESS – SOME EXAMPLES

• Should a Court be able to find that it was unfair to retrench employees at a loss-making branch of its business because the costs of employing employees in this loss-making branch could easily be subsidised by other profitable branches.

• Should a Court be permitted to find that dismissals arising from a decision to close a factory, because the product produced at that factory can be imported at a cheaper price and hence sold at a greater profit, is unfair.

• Should a Court be able to decide that it is not necessary for an employer to invest in labour saving machinery, or to alter its product mix and that dismissals that flow from these decisions are accordingly unfair.

9

9

ASSESSING FAIRNESS – SOME EXAMPLES

10

• Should a decision to retrench workers on the basis that the market the employer serves has contracted be overturned by the Court because it is arguable that the market may improve in the future.

• Should a decision to build a new factory with modern production facilities justify the dismissal of long serving employees at an older, less productive, factory?

10

11 ASSESSING FAIRNESS

SA Mutual Life Assurance Society v Insurance & Banking Staff

Association & Others [2001] 9 BLLR 1045 (LC) and NUMSA and Others v

Genlux Lighting (Pty) Ltd [2009] 3 BLLR 245 (LC).

11

12

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

The dismissal must be bona fide and business-like. See Morestêr Bande

(Pty) Ltd v National Union of Metalworkers of SA & Another (1990) 11 ILJ

687 (LAC) and Seven Able CC t/a Crest Hotel v HARWU & Others (1990)

11 ILJ 504 (LAC).

12

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

The decision must be rational. See SA Clothing & Textile Workers Union v

Discreto – a Division of Trump and Springbok Holdings [1998] 12 BLLR

1228 (LAC) where the following was stated:

13

“The function of a Court in scrutinising the consultation process is not to second-guess the commercial or business efficacy of the employer’s ultimate decision (an issue on which it is, generally, not qualified to pronounce upon), but to pass judgment on whether the ultimate decision arrived at was genuine and not merely a sham (the kind of issue which

Courts are called upon to do in different settings, every day). The manner in which the Court adjudges the latter issue is to enquire whether the legal requirements for a proper consultation process has been followed and, if so

13

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

The decision must be rational. See SA Clothing & Textile Workers Union v

Discreto – a Division of Trump and Springbok Holdings [1998] 12 BLLR

1228 (LAC) where the following was stated:

14 whether the ultimate decision arrived at by the employer is operationally and commercially justifiable on rational grounds, having regard to what emerged from the consultation process. It is important to note that when determining the rationality of the employer’s ultimate decision on retrenchment, it is not the

Court’s function to decide whether it was the best decision under the circumstances, but only whether it was a rational commercial or operational decision, properly taking into account what emerged during the consultation process.

”

14

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

The decision must be reasonable. See BMD Knitting Mills (Pty) Ltd v

SACTWU [2001] 7 BLLR 705 (LAC) where the following was stated:

“[19] I have some doubt as to whether this deferential approach which is sourced in the principles of administrative review is equally applicable to a decision by an employer to dismiss employees particularly in the light of the wording of the section of the Act, namely, “the reason for dismissal is a fair reason”. The word “fair” introduces a comparator, that is a reason which must be fair to both parties affected by the decision. The starting point is whether there is a commercial rationale for the decision. But, rather than take such justification at face value, a Court is entitled to examine whether the particular decision has been taken in a manner which is also fair to the affected party, namely the employees to be retrenched. To this extent the Court is entitled to enquire as to

15

15

16

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

The decision must be reasonable. See BMD Knitting Mills (Pty) Ltd v

SACTWU [2001] 7 BLLR 705 (LAC) where the following was stated: whether a reasonable basis exists on which the decision, including the proposed manner, to dismiss for operational requirements is predicated. Viewed accordingly, the test becomes less deferential and the Court is entitled to examine the content of the reasons given by the employer, albeit that the enquiry is not directed to whether the reason offered is the one which would have been chosen by the Court. Fairness, not correctness is the mandated test.

”

16

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

A measure of last resort after all alternatives have been exhausted. See

National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa v Atlantis Diesel

Engines (Pty) Ltd (1993) 14 ILJ 642 (LAC).

17

17

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

See Chemical Workers Industrial Union & Others v Algorax (Pty) Ltd

(2003) 24 ILJ 1917 (LAC):

18

• The argument that a Court should not be critical of a solution that an employer has decided to employ because the Court will not have the business knowledge or expertise should not be taken too far.

• The Court should not hesitate to deal with an issue which requires no special expertise, skills or knowledge, but simply requires “common sense” or “logic”.

18

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

See Chemical Workers Industrial Union & Others v Algorax (Pty) Ltd

(2003) 24 ILJ 1917 (LAC):

• If the employer has chosen a solution that results in dismissals when there is an obvious and clear way in which the problems could have been addressed without employees losing their jobs, or there being fewer job losses, the Court should deal with the matter on the basis of the employer using a solution which preserves jobs, rather than which causes job losses.

• Employers can only resort to dismissals as a measure of last resort.

19

19

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

Some conclusions :

• The Courts have not utilised a single test for assessing fairness.

• Some of these tests have been formulated in differing ways.

• For a discussion see Du Toit et al Labour Relations Law : A

Comprehensive Guide, 5 th Ed 422 – et seq; and Thompson &

Benjamin South African Labour Law AA1-473 – et seq .

20

20

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

Some conclusions :

• As a result it seems that section 189A(19) did not introduce a new test for assessing fairness. It merely reflects, to a large extent, the rationality test.

• Section 189A(19) has had no impact on the development of our law. As far as can be established, there has been no LAC decision analysing it. As far as can be established there is only one Labour Court decision that analyses the section, namely SATAWU V Old Mutual Life Assurance

Company South Africa Ltd [2005] 4 BLLR 378 (LC) which seems to adopt a synthesis of the “reasonableness” and the “rationality test”.

• No distinction has been developed between ordinary retrenchments and

Section 189A retrenchments.

• The repeal of section 189A(19) will not affect our law in any way.

21

21

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

What is the correct test :

• It is tentatively suggested that the rationality test is probably the most satisfactory test.

• The last resort “test” is simply too difficult to apply. It does not sit easily with Court decisions which say that employers have the right to retrench to increase profits.

• In any event, how does one determine which of the alternatives available to an employer should have been adopted. Surely that involves some sort of rationality or reasonableness test.

• A consideration of alternatives as part of the consultation process will be relevant in deciding the question whether the decision was rational.

22

22

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

Selection criteria :

• Choosing the correct selection criteria is also an operational requirement issue.

• Nevertheless, the Courts have been willing to actively second-guess managerial decisions in this regard and, it is submitted, not really addressed the issues.

• It is time for a reconsideration.

23

23

ASSESSING FAIRNESS

• Why is last-in first-out more rational or fair than, for example, first-in firstout?

• What about bumping?

• Why can one not take into account an employee’s performance or disciplinary record as selection criteria?

24

24