Labor Market Equilibrium

1

L

ABOR

M

ARKET

E

QUILIBRIUM

Hewi-Lin Chuang, Ph.D.

2010/03/25

98-101

年促進就業方案

方案目標:

促進勞動市場增加就業機會,減少失業問題,以協

助降低失業率,於 101 年達到 3.0% 之目標。

重點工作項目:

本方案定位為一補強的政策措施,協助降低失業率

,涵蓋短、中、長期的作法。

規劃主軸之六大策略:「擴大產學合作」、「強化

訓練以促進就業與預防失業」、「提升就業媒合成

功率減少摩擦性失業」、「提供工資補貼增加就業

機會」、「協助創業與自僱工作者」,以及「加強

短期促進就業措施」等。

資料來源: http://www.cepd.gov.tw/m1.aspx?sNo=0010829&ex=1&ic=0000015

2

就業市場指標

年月別

15 歲 以

上人口

勞 動 力

人數

就業 失業 勞動力參與率 失 業 率

人數 人數 平均 男 女 平均 男 女

千 人 %

92 年

93 年

94 年

95 年

96 年

17,572 10,076

17,760 10,240

17,949 10,371

9,573

9,786

9,942

18,166 10,522 10,111

503

454

428

411

57.34 67.69 47.14

57.66 67.78 47.71

57.78 67.62 48.12

57.92 67.35 48.68

4.99

4.44

4.13

3.91

5.51

4.83

4.31

4.05

4.25

3.89

3.88

3.71

18,392 10,713 10,294 419 58.25 67.24 49.44

3.91

4.05

3.72

97 年 1-9 月平均 18,594 10,835 10,405 430 58.27 67.12 49.63

3.96

4.16

3.71

就業者之行業結構

年月別

農、林、

漁、牧業

千人 %

工 業

製造業 營造業

服務業

千人 % 千人 % 千人 % 千人 %

92 年

93 年

94 年

95 年

696

642

590

7.27

6.56

5.94

3,398 35.49 2,600 27.16

3,514 35.90 2,681 27.40

3,619 36.40 2,732 27.47

701

732

791

7.32

7.48

7.96

5,480 57.24

5,631 57.54

5,733 57.67

554 5.48

3,700 36.59 2,777 27.46

829 8.20

5,857 57.92

96 年 543 5.28

3,788 36.80 2,842 27.61

846 8.22

5,962 57.92

97 年 1-9 月平均 534 5.13

3,840 36.90 2,888 27.75

848 8.15

6,032 57.97

資料來源:行政院主計處,中華民國台灣地區人力資源調查統計年報、速報。

3

失業規模指標

年月別

總計

初 次 尋 職

者 小 計

非初次尋職者

工作場所業務

緊縮或歇業

對原有工作

不滿意

季節性或 臨

時性工作 結

束

其他

千人 千人 (%) 千人 (%) 千人 (%) 千人 (%) 千人 (%) 千人 (%)

92 年 503 85 16.9 418 83.1 228 45.3 111 22.1 50 9.9 30 6.0

93 年

94 年

454

428

85 18.7 369 81.3 158 34.8 131 28.9 49 10.8 29 6.4

82 19.2 346 80.8 130 30.4 140 32.7 49 11.4 27 6.3

95 年

96 年

411

419

82 20.0 329 80.0 117 28.5 141 34.3 44 10.7 26 6.3

87 20.8 332 79.2 126 30.1 138 32.9 41 9.8 27 6.4

97 年 1-9

年月別

月 430

總 計

90 21.0 340 79.0 134 31.2 140 32.5 42 9.7 24 5.6

失業者之失業週數

年齡別 教育程度別

初次

尋職

非初次

尋職 15-24 歲 25-44 歲 45-64 歲

國中及

以下

高中 ( 職 )

大專及

以上

92 年

93 年

94 年

95 年

30.5

29.4

27.6

29.0

27.0

26.9

30.9

30.0

27.8

24.3 23.2 24.5

96 年 24.2 23.0 24.6

97 年 1-9 月 24.8

25.1

24.8

23.3

21.1

20.4

17.8

17.7

19.0

32.1

31.3

29.1

25.5

25.8

26.7

35.6

35.2

32.9

29.8

28.2

27.1

32.4

31.1

29.7

26.0

25.4

25.2

30.1

29.7

27.4

23.6

24.5

25.2

28.8

27.3

26.2

24.0

24.3

資料來源:行政院主計處,中華民國台灣地區人力資源調查統計年報、速報。

I

NTRODUCTION

Labor market equilibrium coordinates the desires of firms and workers, determining the wage and employment observed in the labor market.

Market types:

Perfect Competition

Monopsony: one buyer of labor

Monopoly: one seller of labor

These market structures generate unique labor market equilibria.

5

L

ABOR

M

ARKET

E

QUILIBRIUM

Workers prefer to work when the wage is high, and firms prefer to hire when the wage is low.

Labor market equilibrium “balance out” the conflicting desires of workers and firms and determines the wage and employment observed in the labor market.

6

1. E QUILIBRIUM IN A S INGLE C OMPETITIVE L ABOR

M ARKET

Dollars

S

The supply curve gives the total number of employeehours that agents in the economy allocate to the market at any given wage level; the demand curve gives the total number of employee-hours that firms in the market demand at that wage. Equilibrium occurs when supply equals demand, generating the competitive wage w * and employment E *.

W*

E*

D

Employment

Equilibrium in a Competitive Labor Market

Note: There is no unemployment in a competitive labor market. Persons who are not working are also not looking for work at the going wage .

7

Note: The “single wage” property of competitive equilibrium has important implications for economic performance. That is, workers of given skills have the same value of marginal product of labor in all markets. The allocation of workers to firms which equates the value of marginal product across markets is also the allocation which maximizes national income. This type of allocation is called an efficient allocation .

8

(P

ARETO

) E

FFICIENCY

Pareto efficiency exists when all possible gains from trade have been exhausted.

When the state of the world is Pareto Efficient, to improve one person’s welfare necessarily requires decreasing another person’s welfare.

In policy applications, ask whether a change can make any one better off without harming anyone else. If the answer is yes, then the proposed change is said to be

“Pareto-improving”.

9

E

QUILIBRIUM IN A

C

OMPETITIVE

L

ABOR

M

ARKET

Dollars w *

P

Q

E

L

E * E

H

S

D

0

Employment

The labor market is in equilibrium when supply equals demand; E* workers are employed at a wage of w* .

In equilibrium, all persons who are looking for work at the going wage can find a job.

The triangle P gives the producer surplus; the triangle

Q gives the worker surplus. A competitive market maximizes the gains from trade, or the

10 sum P + Q .

E

FFICIENCY

R

EVISITED

The “single wage” property of a competitive equilibrium has important implications for economic efficiency.

Recall that in a competitive equilibrium the wage equals the value of marginal product of labor. As firms and workers move to the region that provides the best opportunities, they eliminate regional wage differentials. Therefore, workers of given skills have the same value of marginal product of labor in all markets.

The allocation of workers to firms that equates the value of marginal product across markets is also the sorting that leads to an efficient allocation of labor resources. 11

2. C OMPETITIVE E QUILIBRIUM A CROSS L ABOR M ARKETS

The economy typically consists of many labor markets, even for workers who have similar skills. As long as either workers or firms are free to enter and exit labor markets, a competitive economy will be characterized by a single wage.

Dollars

S

N

Dollars

S’

N

S’

S

W

N

W*

S

S

W*

W

S

D

N

D

S

Employment Employment

Competitive Equilibrium in Two Labor Markets Linked by Migration

12

C

OMPETITIVE

E

QUILIBRIUM

A

CROSS

L

ABOR

M

ARKETS

If workers were mobile and entry and exit of workers to the labor market was free, then there would be a single wage paid to all workers.

The allocation of workers to firms equating the wage to the value of marginal product is also the allocation that maximizes national income (this is known as allocative efficiency).

The “invisible hand” process: self-interested workers and firms accomplish a social goal that no one had in mind, i.e., allocative efficiency.

13

教育別薪資差異

14

產業別就業人數-高教育者

15

產業別就業人數-低教育者

16

台灣教育別薪資差異

新台幣 ( 元 )

1995-2009 年台灣教育別受雇者每月工作收入

(2005 年 CPI 平減後 )

50000

45000

40000

35000

30000

25000

20000

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009

國中及以下 高中

(

職

)

大專及以上

17

3. THE COBWEB MODEL

Our analysis of labor market equilibrium assumes that markets adjust instantaneously to shifts in either supply or demand curves, so that wages and employment change swiftly from the old equilibrium levels to the new equilibrium level. Many labor markets, however, do not adjust so quickly to shifts in the underlying supply and demand curves.

Example: the Engineering Market

Note: The adjustment of college enrollments to changes in the returns to education is not always smooth or rapid, particularly in fields that are highly technical.

→ The inability to respond immediately to changed market conditions can cause boom-and-bust cycles in the market for highly technical workers.

18

Wage

W

1

W

3

W e

W

2

W

0

S

D

’

N

0

N

2

D

N

3

N

1

Number of Engineers

Demand increase to D’ temporary supply is N

0

→ W increase to W

1

→ W

1 wage induce increase in supply to N

→ W reduce to W

2

→ W

2

1

→ excess supply wage reduce supply to N

2

→ W increase to W

3

→ at W

3

, supply increase to N

→ excess supply → W reduces, etc.

3

19

Overtime the swings become smaller and eventually equilibrium is reached. → cobweb model.

Note: There are two key assumptions in the cobweb model:

1.

2.

It takes time to produce new engineers, so that the supply of engineers can be thought of as being perfectly inelastic in the short run.

Students are very myopic when they are considering whether to become engineers.

20

4. POLICY APPLICATION: PAYROLL

TAXES

Payroll taxes on employers are heavily used in the social insurance area. With our simple labor model, we can show that the party making the social insurance payment is not necessarily the one that bears the burden of the tax.

Tax

Real Wage

W

0

+λ

W

1

+X

W

0

W

1

S

0

D

0

Tax is a fixed dollar amount X.

D

0

→D

1 with vertical distance of X. pt. A: excess supply→ real wage↓

Employees bear part of the burden of the payroll tax in the form of lower wage rates and lower employment levels.

Note: In general, the extent to which the labor supply curve is sensitive to wages determines the proportion of the employer

D

1

E

2

E

1

E

0

Employment wages.

P

AYROLL

T

AXES AND

S

UBSIDIES

Payroll taxes assessed on employers lead to a downward, parallel shift in the labor demand curve.

The new demand curve shows a wedge between the amount the firm must pay to hire a worker and the amount that workers actually receive.

Payroll taxes increase total costs of employment, so these taxes reduce employment in the economy.

Firms and workers share the cost of payroll taxes, since the cost of hiring a worker rises and the wage received by workers declines.

Payroll taxes result in deadweight losses.

22

w

0

+ 1 w

1 w

0 w

1

1

T

HE

I

MPACT OF A

P

AYROLL

T

AX

A

SSESSED ON

W

ORKERS

S

1

Dollars

S

0

D

0

A payroll tax assessed on workers shifts the supply curve to the left

(from S

0 to S

1

). The payroll tax has the same impact on the equilibrium wage and employment regardless of who it is assessed on.

D

1

E

1

E

0

Employment

23

T

HE

I

MPACT OF A

P

AYROLL

T

AX PUT

ON

F

IRMS WITH

I

NELASTIC

S

UPPLY

Dollars w

0 w

0

– 1

E

0

S

D

0

A

B

D

0

D

1

Employment

A payroll tax assessed on the firm is shifted completely to workers when the labor supply curve is perfectly inelastic. The wage is initially w

0

. The $1 payroll tax shifts the demand curve to D

1

, and the wage falls to w

0

– 1.

24

P

AYROLL

S

UBSIDIES

An employment subsidy lowers the cost of hiring for firms.

This means payroll subsidies shift the demand curve for labor to the right (up).

Total employment will increase as the cost of hiring has fallen.

25

w

0

+ 1 w

1 w

0 w

1

– 1

T

HE

I

MPACT OF AN

E

MPLOYMENT

S

UBSIDY

S

A

B

An employment subsidy of $1 per worker hired shifts up the labor demand curve, increasing employment. The wage that workers receive rises from w

0 to w

1

. The wage that firms actually pay falls from w

0 to w

1

– 1.

D

1

D

0

E

0

E

1

Employment

26

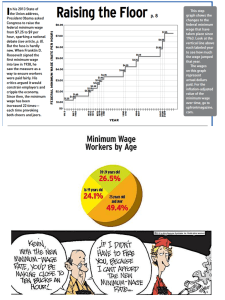

5. P OLICY A PPLICATION : T HE I MPACT OF M INIMUM W AGES

The standard economic model of the impact of minimum wages on employment is illustrated in the following figure:

Dollars

W

W*

E

E* E

S

S

D

Employment

Note: A minimum wage creates unemployment both because some previously employed workers lose their jobs, and because some workers who did not find it worthwhile to work at the competitive wage find it worthwhile to work at the higher minimum wage.

27

The Impact of the Minimum Wage on Employment

T

HE

I

MPACT OF

M

INIMUM

W

AGES ON THE

C

OVERED AND

U

NCOVERED

S

ECTORS

Dollars Dollars

S

C

S

U

(If workers migrate to

S

U covered sector) w

w * w *

S

U

(If workers migrate to uncovered sector)

E

E

C

(a) Covered Sector

D

C

Employment E

U

E

U

E

U

D

U

Employment

(b) Uncovered Sector

If the minimum wage applies only to jobs in the covered sector, the displaced workers might move to the uncovered sector, shifting the supply curve to the right and reducing the uncovered sector’s wage. If it is easy to get a minimum wage job, workers in the uncovered sector might quit their jobs and wait in the covered sector until a job opens up, shifting the supply curve in the uncovered sector to the left and raising the uncovered sector’s wage.

28

Note: In the absence of a minimum wage, the migration of workers across sectors equates the wage in the two sectors. The migration of workers when the wage in one of the markets is set at the minimum wage equates the expected wage across sectors. I.e., the free migration of workers across sectors ensure that the expected wage in the covered sector equals the for-sure wage in the uncovered sector.

29

6. N

ONCOMPETITIVE

L

ABOR

M

ARKETS

(1)

Monopsony

Because the firm is the only demander of labor in this market, it can influence the wage rate.

Monopsnoists face an upward-sloping supply curve. This is because the supply curve confronting them is the market supply curve.

Note: To expand its work force, a monopsonist must increase its wage rate, i.e., the marginal cost of hiring labor excess the wage.

30

N

ONCOMPETITIVE

L

ABOR

M

ARKETS

: M

ONOPSONY

Monopsony market exists when a firm is the only buyer of labor.

Monopsonists must increase wages to attract more workers.

Two types of monopsonist firms:

Perfectly discriminating

Nondiscriminating

31

P

ERFECTLY

D

ISCRIMINATING

M

ONOPSONIST

Discriminating monopsonists are able to hire different workers at different wages.

To maximize firm surplus (profits), a perfectly discriminating monopsonist “perfectly discriminates” by paying each worker his or her reservation wage.

32

w * w

30 w

10

T

HE

H

IRING

D

ECISION OF A

P

ERFECTLY

D

ISCRIMINATING

M

ONOPSONIST

Dollars

A

S

VMP

E

10 30 E * Employment

A perfectly discriminating monopsonist faces an upwardsloping labor supply curve and can hire different workers at different wages. Therefore the labor supply curve gives the marginal cost of hiring. Profit maximization occurs at point

A . The monopsonist hires the same number of workers as a competitive market, but each worker is paid his or her reservation wage.

33

N

ONDISRIMINATING

M

ONOPSONIST

Must pay all workers the same wage, regardless of each worker’s reservation wage.

Must raise the wage of all workers when attempting to attract more workers.

Employs fewer workers than would be employed if the market were competitive.

34

T

HE

H

IRING

D

ECISION OF A

N

ONDISCRIMINATING

M

ONOPSONIST

Dollars

VMP

M w * w

M

A

E

M

E

*

MC

E

S

VMP

E

A nondiscriminating monopsonist pays the same wage to all workers. The marginal cost of hiring exceeds the wage, and the marginal cost curve lies above the supply curve.

Profit maximization occurs at point A ; the monopsonist hires E

M workers and pays

Employment them all a wage of w

M

.

35

To maximize profits, we know that any firm should hire labor until the points at which marginal revenue product equals marginal cost.

W

C

W m

W

E m

E c

MC

L

S

MRP = MC

L

Wages are below marginal revenue product for a monopsonist.

MRP

L

W m

< W

C and E m

< E

C

36

T HE I MPACT OF THE M INIMUM W AGE ON A

N ONDISCRIMINATING M ONOPSONIST

Dollars w * w w

M

A

E

M

E

MC

E

S

VMP

E

Employment

The minimum wage may increase both wages and employment when imposed on a nondiscriminating monopsonist. A minimum wage set at w

increases employment to E

.

37

(2) Monopoly

A monopoly trying to maximize profits and facing a competitive labor market will hire workers until its marginal revenue product equals the wage rate:

MRP = (MP

L

)(MR) = W

→ (MR/P)(MP

L

) = (W/P) <1

The demand-for-labor curve for a firm that has monopoly power in the output market will lie below and to the left of the demand-for-labor curve for an otherwise identical firm that takes product prices as given.

38

M

ONOPOLY IN THE

P

RODUCT

M

ARKET

:

A R

EVIEW

Firms that have monopoly power can influence the price of the product that they sell.

Monopolist faces a downward sloped market demand curve for its output and an even lower downward sloped marginal revenue curve.

39

T

HE

O

UTPUT

D

ECISION OF A

M

ONOPOLIST

Dollars p

M p *

A q

M q *

MR

MC

D

Output

A monopolist faces a downward-sloping demand curve for her output. The marginal revenue from selling an additional unit of output is less than the price of the product. Profit maximization occurs at point A where the monopolist produces q

M units of output and sells each unit of output at a price of p

M dollars.

40

Note: The wage rates that monopolies pay are not necessarily different from competitive levels even though employment levels are. An employer with a product market monopoly may still be a very small part of the market for a particular kind of employee, and thus be a price taker in the labor market even though a price maker in the product market.

Dollars

A

W

VMP

E

MRP

E

E m

E* Employment

The Labor Demand of a Monopolist

41