Chapter 1 Digital Systems and Binary Numbers

授課教師: 張傳育 博士 (Chuan-Yu Chang Ph.D.)

E-mail: chuanyu@yuntech.edu.tw

Tel: (05)5342601 ext. 4337

Office: EB212

1

Digital Logic Design

• Text Book

– M. M. Mano and M. D. Ciletti, “Digital Design," 4th Ed., Pearson

Prentice Hall, 2007.

• Reference

– class notes

• Grade

–

–

–

–

Quizzes:

Mid-term:

Final:

Appearance:

2

Chapter 1: Digital Systems and Binary Numbers

• Digital age and information age

• Digital computers

– general purposes

– many scientific, industrial and commercial applications

• Digital systems

–

–

–

–

telephone switching exchanges

digital camera

electronic calculators, PDA's

digital TV

• Discrete information-processing systems

– manipulate discrete elements of information

3

Signal

• An information variable represented by physical quantity

• For digital systems, the variable takes on discrete values

– Two level, or binary values are the most prevalent values

• Binary values are represented abstractly by:

–

–

–

–

digits 0 and 1

words (symbols) False (F) and True (T)

words (symbols) Low (L) and High (H)

and words On and Off.

• Binary values are represented by values or ranges of

values of physical quantities

4

Signal Example – Physical Quantity: Voltage

OUTPUT

INPUT

5.0

HIGH

4.0

3.0

2.0

LOW

1.0

HIGH

Threshold

Region

LOW

0.0

Volts

5

Signal Examples Over Time

Time

Analog

Digital

Continuous in

value & time

Asynchronous

Discrete in

value &

continuous in

time

Synchronous

Discrete in

value & time

6

A Digital Computer Example

Memory

CPU

Inputs: Keyboard,

mouse, modem,

microphone

Control

unit

Datapath

Input/Output

Outputs: CRT,

LCD, modem,

speakers

Synchronous or

Asynchronous?

7

Binary Numbers and Binary Coding

• Information Types

– Numeric

» Must represent range of data needed

» Represent data such that simple, straightforward computation for

common arithmetic operations

» Tight relation to binary numbers

– Non-numeric

» Greater flexibility since arithmetic operations not applied.

» Not tied to binary numbers

8

Number of Elements Represented

• Given n digits in radix r, there are rn distinct

elements that can be represented.

• But, you can represent m elements, m < rn

• Examples:

– You can represent 4 elements in radix r = 2 with n = 2

digits: (00, 01, 10, 11).

– You can represent 4 elements in radix r = 2 with n = 4

digits: (0001, 0010, 0100, 1000).

– This second code is called a "one hot" code.

9

Non-numeric Binary Codes

• Given n binary digits (called bits), a binary code is a

mapping from a set of represented elements to a

subset of the 2n binary numbers.

• Example: A

Color

Binary Number

binary code

Red

000

for the seven

Orange

001

colors of the

Yellow

010

rainbow

Green

011

Blue

101

• Code 100 is

Indigo

110

not used

Violet

111

10

Binary Numbers

• Decimal number

Base or radix

aj

… a5a4a3a2a1.a1a2a3…

Decimal point

Power

105 a5 104 a4 103 a3 102 a2 101 a1 100 a0 101 a1 102 a2 103 a3

Example:

7,329 7 103 3 102 2 101 9 100

• General form of base-r system

an rn an1 rn1

a2 r 2 a1 r1 a0 a1 r 1 a2 r 2

am r m

Coefficient: aj = 0 to r 1

11

Binary Numbers

Example: Base-2 number

(11010.11)2 (26.75)10

1 24 1 23 0 22 1 21 0 20 1 2 1 1 2 2

Example: Base-5 number

4021.25

4 53 0 5 2 2 51 1 50 2 5 1 511.410

Example: Base-8 number

127.48

1 8 2 2 81 7 80 4 8 1 87.510

Example: Base-16 number

(B65F)16 11 163 6 162 5 161 15 160 (46,687)10

12

Converting Binary to Decimal

• To convert to decimal, use decimal arithmetic to form S (digit ×

respective power of 2).

• Example:Convert 110102 to N10:

13

Binary Numbers

Example: Base-2 number

(110101)2 32 16 4 1 (53)10

Special Powers of 2

210 (1024) is Kilo, denoted "K"

220 (1,048,576) is Mega, denoted "M"

230 (1,073, 741,824)is Giga, denoted "G"

Powers of two

Table 1.1

14

Arithmetic operation

Arithmetic operations with numbers in base r follow the same rules as decimal

numbers.

15

Binary Arithmetic

•

•

•

•

•

•

Single Bit Addition with Carry

Multiple Bit Addition

Single Bit Subtraction with Borrow

Multiple Bit Subtraction

Multiplication

BCD Addition

16

Single Bit Binary Addition with Carry

Given two binary digits (X,Y), a carry in (Z) we get the

following sum (S) and carry (C):

Carry in (Z) of 0:

Carry in (Z) of 1:

Z

X

+Y

0

0

+0

0

0

+1

0

1

+0

0

1

+1

CS

00

01

01

10

Z

X

+Y

1

0

+0

1

0

+1

1

1

+0

1

1

+1

CS

01

10

10

11

17

Multiple Bit Binary Addition

• Extending this to two multiple bit examples:

Carries

Augend

Addend

Sum

0

0

01100 10110

+10001 +10111

• Note: The 0 is the default Carry-In to the least significant bit.

18

Binary Arithmetic

• Subtraction

• Addition

Augend:

Minuend:

101101

Subtrahend: 100111

Addend: +100111

The binary multiplication table is simple:

Difference:

Sum:

101101

1010100

000110

00=0 | 10=0 | 01=0 | 11=1

•Extending

Multiplication

multiplication to multiple digits:

Multiplicand

Multiplier

Partial Products

Product

1011

101

1011

0000 1011 - 110111

19

Number-Base Conversions

Name

Radix

Digits

Binary

2

0,1

Octal

8

0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7

Decimal

10

0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9

Hexadecimal

16

0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,A,B,C,D,E,F

The six letters (in addition to the 10 integers) in

hexadecimal represent: 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15,

respectively.

20

Number-Base Conversions

Example1.1

Convert decimal 41 to binary. The process is continued until the integer quotient

becomes 0.

21

Number-Base Conversions

The arithmetic process can be manipulated more conveniently as follows:

22

Number-Base Conversions

Example 1.2

Convert decimal 153 to octal. The required base r is 8.

Example1.3

Convert (0.6875)10 to binary.

The process is continued until the fraction becomes 0 or until the number of digits has

sufficient accuracy.

23

Number-Base Conversions

Example1.3

To convert a decimal fraction to a number expressed in base r, a similar

procedure is used. However, multiplication is by r instead of 2, and the

coefficients found from the integers may range in value from 0 to r 1

instead of 0 and 1.

24

Number-Base Conversions

Example1.4

Convert (0.513)10 to octal.

From Examples 1.1 and 1.3:

(41.6875)10 = (101001.1011)2

From Examples 1.2 and 1.4:

(153.513)10 = (231.406517)8

25

Octal and Hexadecimal Numbers

Numbers with different bases: Table 1.2.

26

Octal and Hexadecimal Numbers

Conversion from binary to octal can be done by positioning the binary number into

groups of three digits each, starting from the binary point and proceeding to the left

and to the right.

(10 110 001 101 011

2

6

1

5

3

.

111

100

000

7

4

0

110) 2 = (26153.7406)8

6

Conversion from binary to hexadecimal is similar, except that the binary number is

divided into groups of four digits:

Conversion from octal or hexadecimal to binary is done by reversing the preceding

procedure.

27

Complements

There are two types of complements for each base-r system: the radix complement and

diminished radix complement.

the r's complement and the second as the (r 1)'s complement.

■ Diminished Radix Complement

Example:

For binary numbers, r = 2 and r – 1 = 1, so the 1's complement of N is (2n 1) – N.

Example:

28

Complements (cont.)

■ Radix Complement

The r's complement of an n-digit number N in base r is defined as rn – N for N ≠ 0

and as 0 for N = 0. Comparing with the (r 1) 's complement, we note that the r's

complement is obtained by adding 1 to the (r 1) 's complement, since rn – N = [(rn

1) – N] + 1.

Example: Base-10

The 10's complement of 012398 is 987602

The 10's complement of 246700 is 753300

Example: Base-10

The 2's complement of 1101100 is 0010100

The 2's complement of 0110111 is 1001001

29

Complements (cont.)

■ Subtraction with Complements

The subtraction of two n-digit unsigned numbers M – N in base r can be done as follows:

30

Complements (cont.)

Example 1.5

Using 10's complement, subtract 72532 – 3250.

Example 1.6

Using 10's complement, subtract 3250 – 72532

There is no end carry.

Therefore, the answer is – (10's complement of 30718) = 69282.

31

Complements (cont.)

Example 1.7

Given the two binary numbers X = 1010100 and Y = 1000011, perform the subtraction (a)

X – Y and (b) Y X by using 2's complement.

There is no end carry.

Therefore, the answer is

Y – X = (2's complement

of 1101111) = 0010001.

32

Complements (cont.)

Subtraction of unsigned numbers can also be done by means of the (r 1)'s

complement. Remember that the (r 1) 's complement is one less then the r's

complement.

Example 1.8

Repeat Example 1.7, but this time using 1's complement.

There is no end carry,

Therefore, the answer is

Y – X = (1's complement

of 1101110) = 0010001.

33

Signed Binary Numbers

To represent negative integers, we need a notation for negative values.

It is customary to represent the sign with a bit placed in the leftmost position of the

number.

The convention is to make the sign bit 0 for positive and 1 for negative.

Example:

Table 3 lists all possible four-bit signed binary numbers in the three representations.

34

Signed Binary Numbers (cont.)

35

Signed Binary Numbers (cont.)

■ Arithmetic Addition

The addition of two numbers in the signed-magnitude system follows the rules of

ordinary arithmetic. If the signs are the same, we add the two magnitudes and give

the sum the common sign. If the signs are different, we subtract the smaller

magnitude from the larger and give the difference the sign if the larger magnitude.

The addition of two signed binary numbers with negative numbers represented in

signed-2's-complement form is obtained from the addition of the two numbers,

including their sign bits.

A carry out of the sign-bit position is discarded.

Example:

36

Signed Binary Numbers (cont.)

■ Arithmetic Subtraction

In 2’s-complement form:

1.

2.

Take the 2’s complement of the subtrahend (including the sign bit) and add it to

the minuend (including sign bit).

A carry out of sign-bit position is discarded.

( A) ( B) ( A) ( B)

( A) ( B) ( A) ( B)

Example:

( 6) ( 13)

(11111010 11110011)

(11111010 + 00001101)

00000111 (+ 7)

37

Binary Coded Decimal (BCD)

• The BCD code is the 8,4,2,1 code.

• This code is the simplest, most intuitive binary code

for decimal digits and uses the same powers of 2 as

a binary number, but only encodes the first ten

values from 0 to 9.

• Example: 1001 (9) = 1000 (8) + 0001 (1)

• How many “invalid” code words are there?

• What are the “invalid” code words?

38

Binary Codes

■ BCD Code

A number with k decimal digits will

require 4k bits in BCD. Decimal 396

is represented in BCD with 12bits as

0011 1001 0110, with each group of

4 bits representing one decimal digit.

A decimal number in BCD is the

same as its equivalent binary

number only when the number is

between 0 and 9. A BCD number

greater than 10 looks different from

its equivalent binary number, even

though both contain 1's and 0's.

Moreover, the binary combinations

1010 through 1111 are not used and

have no meaning in BCD.

39

Warning: Conversion or Coding?

• Do NOT mix up conversion of a decimal number to a binary

number with coding a decimal number with a BINARY CODE.

• 1310 = 11012 (This is conversion)

• 13 0001|0011 (This is coding)

40

BCD Arithmetic

Given a BCD code, we use binary arithmetic to add the digits:

8

1000

Eight

+5

+0101

Plus 5

13

1101

is 13 (> 9)

Note that the result is MORE THAN 9, so must be

represented by two digits!

To correct the digit, subtract 10 by adding 6 modulo 16.

8

1000 Eight

+5

+0101 Plus 5

13

1101 is 13 (> 9)

+0110 so add 6

carry = 1 0011

leaving 3 + cy

0001 | 0011

Final answer (two digits)

If the digit sum is > 9, add one to the next significant digit

41

BCD Addition Example

• Add 2905BCD to 1897BCD showing carries

and digit corrections.

0001

+ 0010

0011

+0001

0100

4

1000

1001

10001

+0110

10111

+0001

11000

8

1001

0000

1001

+0001

1010

+0110

10000

0

0111

0101

1100

+0110

10010

2

42

Binary Codes

Example:

Consider decimal 185 and its corresponding value in BCD and binary:

■ BCD Addition

43

Binary Codes

Example:

Consider the addition of 184 + 576 = 760 in BCD:

■ Decimal Arithmetic

44

Binary Codes

■ Other Decimal Codes

45

Binary Codes

■ Gray Code

46

Gray Code

Decimal

8,4,2,1

Gray

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0000

0001

0010

0011

0100

0101

0110

0111

1000

1001

0000

0100

0101

0111

0110

0010

0011

0001

1001

1000

• What special property does the Gray code have

in relation to adjacent decimal digits?

47

Gray Code (Continued)

• Does this special Gray code property have any

value?

• An Example: Optical Shaft Encoder

111

000

100

000

B0

B1

110

001

B2

010

101

100

011

(a) Binary Code for Positions 0 through 7

101

111

001

G0

G1

G2

011

110

010

(b) Gray Code for Positions 0 through 7

48

Binary Codes

■ ASCII Character Code

49

Binary Codes

■ ASCII Character Code

50

ASCII Character Codes

• American Standard Code for Information

Interchange (Refer to Table 1.7)

• A popular code used to represent information sent as

character-based data.

• It uses 7-bits to represent:

– 94 Graphic printing characters.

– 34 Non-printing characters

• Some non-printing characters are used for text

format (e.g. BS = Backspace, CR = carriage return)

• Other non-printing characters are used for record

marking and flow control (e.g. STX and ETX start

and end text areas).

51

ASCII Properties

ASCII has some interesting properties:

Digits 0 to 9 span Hexadecimal values 3016 to 3916 .

Upper case A - Z span 4116 to 5A16 .

Lower case a - z span 6116 to 7A16 .

• Lower to upper case translation (and vice versa)

occurs by flipping bit 6.

Delete (DEL) is all bits set, a carryover from when

punched paper tape was used to store messages.

Punching all holes in a row erased a mistake!

52

Binary Codes

■ Error-Detecting Code

To detect errors in data communication and processing, an eighth bit is sometimes

added to the ASCII character to indicate its parity.

A parity bit is an extra bit included with a message to make the total number of 1's

either even or odd.

Example:

Consider the following two characters and their even and odd parity:

53

Binary Codes

■ Error-Detecting Code

• Redundancy (e.g. extra information), in the form of extra

bits, can be incorporated into binary code words to detect

and correct errors.

• A simple form of redundancy is parity, an extra bit

appended onto the code word to make the number of 1’s

odd or even. Parity can detect all single-bit errors and

some multiple-bit errors.

• A code word has even parity if the number of 1’s in the

code word is even.

• A code word has odd parity if the number of 1’s in the

code word is odd.

54

4-Bit Parity Code Example

• Fill in the even and odd parity bits:

Even Parity

Odd Parity

Message - Parity Message - Parity

000 - 1

000 - 0

001 - 0

001 - 1

010 - 0

010 - 1

011 - 1

011 - 0

100 - 0

100 - 1

101 - 1

101 - 0

110 - 1

110 - 0

111 - 0

111 - 1

• The codeword "1111" has even parity and the codeword

"1110" has odd parity. Both can be used to represent 3bit data.

55

UNICODE

• UNICODE extends ASCII to 65,536

universal characters codes

– For encoding characters in world languages

– Available in many modern applications

– 2 byte (16-bit) code words

– See Reading Supplement – Unicode on the

Companion Website

http://www.prenhall.com/mano

56

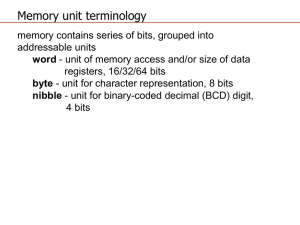

Binary Storage and Registers

■ Registers

A binary cell is a device that possesses two stable states and is capable of storing

one of the two states.

A register is a group of binary cells. A register with n cells can store any discrete

quantity of information that contains n bits.

n cells

2n possible states

• A binary cell

– two stable state

– store one bit of information

– examples: flip-flop circuits, ferrite cores, capacitor

• A register

– a group of binary cells

– AX in x86 CPU

• Register Transfer

– a transfer of the information stored in one register to another

– one of the major operations in digital system

– an example

57

Transfer of information

58

• The other major component of a digital system

– circuit elements to manipulate individual bits of information

59

Binary Logic

■ Definition of Binary Logic

Binary logic consists of binary variables and a set of logical operations. The variables

are designated by letters of the alphabet, such as A, B, C, x, y, z, etc, with each

variable having two and only two distinct possible values: 1 and 0, There are three

basic logical operations: AND, OR, and NOT.

60

Binary Logic

■ The truth tables for AND, OR, and NOT are given in Table 1.8.

61

Binary Logic

■ Logic gates

Example of binary signals

62

Binary Logic

■ Logic gates

Graphic Symbols and Input-Output Signals for Logic gates:

Fig. 1.4 Symbols for digital logic circuits

Fig. 1.5

Input-Output signals

for gates

63

Binary Logic

■ Logic gates

Graphic Symbols and Input-Output Signals for Logic gates:

Fig. 1.6 Gates with multiple inputs

64