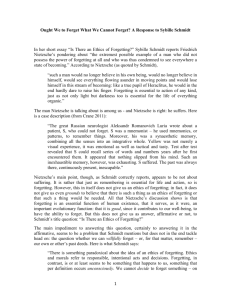

directed forgetting in children?

advertisement

Directed Forgetting in Preschoolers: Comparisons between retrieval inhibition and context change models Victoria Shiebler, Advisor: Almut Hupbach Department of Psychology, Lehigh University Design Introduction • One way to change memory is through the method of directed forgetting which may be explained by two competing theories: retrieval inhibition (e.g., Bjork, 1972) and the context change model (Sahaykyan and Kelley , 2002) Forget/ Remember List 2 Recall List 1 List 2 DIRECTED FORGETTING IN CHILDREN? • Harnishfeger and Pope (1996) failed to show the costs or benefits of directed forgetting in kindergarteners. Overall recall for the word lists was very low. Researchers have hypothesized that the lack of DF effects in young children may be due to later-developing brain processes essential for inhibitory processes or a production deficiency stage. • The present study aimed to examine if preschoolers can in fact show directed forgetting effects using concrete objects and clear instructions. Retrieval Inhibition vs. Context Change Manipulations that cause forgetting/mental context change Instruction to forget Imagine being invisible L1 L2 Retrieval Daydreaming Retrieval of prior List • If DF is due to inhibition, then young children should not show DF effects due to the late development of inhibitory processes (prefrontal cortex). PART 1 CUE PART 2 80 Chatting, wiping computer monitor Mechanistic Forget Cue N=17 4&5-yr-olds Context Change N=18 4&5-yr-olds Remember N=15 4&5-yr-olds Memory Performance PART 3 List 1 • Previous directed forgetting studies have shown that adults display robust directed forgetting effects: impaired recall for list 1 (costs) and enhanced recall for list 2 (benefits) (e.g., Bjork, 1989). • If the context change theory explains directed forgetting, children should have no problem intentionally forgetting objects through a mental context change. Experimental Group Please empty your brain to make space for the second set of objects. Learn Set 1 Please describe your favorite toy in detail Both sets of objects will be important for the end of the memory game Learn Set 2, distract task Recall task of all 16 objects Percent objects recalled • Memory is not only forgotten unintentionally, but can also be intentionally forgotten. Results Recall Set 1 (Costs) 70 Recall Set 2 (Benefits) 60 50 40 30 20 10 Animal Name Memory Task Directed Forgetting Paradigm Distractor Task: What is your favorite food/ what are you having for lunch today? Animal Name Working Memory Task: Repeat increasing number of animal name spans Children given points for each correct span References •Aslan, A., & Bäuml, K. (2008). Memorial consequences of imagination of children and adults. Psychodynamic Bulletin and Review, 15(4), 833-837. •Aslan, A., Zellner, M., & Bäuml, K. (2010). Working memory capacity predicts listwise directed forgetting in adults and children. Psychology Press, 18(4), 442-450. •Basden, B., & Basden, D. (1996). Directed forgetting: Further comparison of the item and list methods. Memory, 6(4), 633-653. •Bjork, R. A. (1989). Retrieval inhibition as an adaptive mechanism in human memory. In H. L.Roediger III & F. I. M. Craik (Eds.), Varieties of memory & consciousness. •Harnishfeger, K., & Pope, R. (1996). Intending to forget: The development of cognitive inhibition in directed forgetting. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 62, 292-315. •Howe, M. (2005). Children (but not adults) can inhibit false memories. Psychological Science, 16(12), 927-931. •Sahakyan, L., & Kelley, C. (2002). A contextual change account of the directed forgetting effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 28(6), 1064-1072. 0 forget context change Condition remember • Children in both, the forget cue and the context change group showed both costs and benefits of directed forgetting. • Impaired Recall of Set 1 • Enhanced Recall of Set 2 • Memory performance for sets of objects was not related to working memory task. Discussion • Preschoolers ages 4 and 5 can in fact display directed forgetting effects. • Concrete objects and clear instructions improved baseline memory for objects, which allowed us to properly assess directed forgetting costs and benefits. • Regardless of instruction, children remembered list 2 items better than list 1 items due to a recency effect, which could be eliminated in future studies with a longer experiment period. • Directed forgetting is mediated by context change because preschoolers displayed effects although their memory suppressing mechanisms are not fully developed. • Both the forget in instruction as well as the context change instruction induced a mental context change, which created a mismatch between list 1 learning and recall (Sahakyan and Kelley, 2002). • Since working memory and directed forgetting effects were not correlated in this study, directed forgetting does not rely on working memory brain structures. This provides more evidence for the fact that directed forgetting is mediated by a mental context change.