Urolithiasis - Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences

advertisement

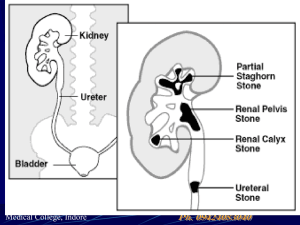

UROLITHIASIS Dr Zakir Hussain Rajpar Assistant Professor Of Urology Liaquat University Of Medical And Health Sciences Urolithiasis Urolithiasis (from Greek oûron-urine and lithos-stone) is the condition where urinary stones are formed or located anywhere in the urinary system. Background Urolithiasis Kidney stones Ureteral stones Bladder stones Urethral stones Background Urolithiasis is a common disease that is estimated to produce medical costs of $2.1 billion per year in the United States alone. Urolithiasis has been a part of the human condition for millennia and have even been found in Egyptian mummies. Background Renal colic affects approximately 1.2 million people each year in USA and accounts for approximately 1% of all hospital admissions. Most active emergency departments (EDs) manage patients with acute renal colic every day Epidemiology Epidemiology Urolithiasis occurs in all parts of the world A lifetime risk: 2-5% for Asia 8-15% for the West Hot Climate Dietary habits Hereditary factors Epidemiology The lower the economic status, the lower the likelihood of renal stones Most at 20-49 years Peak incidence at 35-45 years Male-to-female ratio of 3:1 Chemical types and etiology Chemical Types Four main chemical types: Calcium stones Struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) stones Uric acid stones Cystine stones Calcium stones Calcium stones account for 75% of Urolithiasis. Radio-opaque Multiple factors and etiologies Mostly incidental Calcium Stone Known etiologies Incidental Hyperparathyroidism Increased gut absorption of calcium Renal calcium leak Renal phosphate leak Hperuricosuria Hperoxaluria Hypocitraturia Hypomagnesuria Calcium Stone Struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) stones Account for 15% of renal calculi Infectous stones Gram-negative rods capable of splitting urea into ammonium, which combines with phosphate and magnesium More common in females Urine pH is typically greater than 7 Struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) stones Stag horn stones are non obstructive thus painless Slowly growing Discovered incidentally Uric acid stones Account for 6% of renal calculi Urine pH less than 5.5 High purine intake eg. organ meats legumes malignancy 25% of patients have gout Uric Acid Stones Uric Acid Stones Cystine stones 2% of renal calculi Autosomal recessive trait Intrinsic metabolic defect resulting in failure of renal tubular reabsorption of: Cystine Ornithine Lysine Arginine Urine becomes supersaturated with cystine, with resultant crystal deposition Cystine Stones Radio-faint History History The presentation is variable. Patients with urinary calculi may report Pain Infection Hematuria Asymptomatic Silent Kidney stones Obstructive ureteral stone The passage of stones into the ureter is associated with classic renal colic because of: subsequent acute obstruction proximal urinary tract dilation ureteral spasm Acute renal colic is probably the most excruciatingly painful event a person can endure Classic Renal Colic Acute onset of severe flank pain radiating to the groin Gross or microscopic hematuria Nausea, and vomiting not associated with an acute abdomen in 50% Staghorn stone Staghorn calculi are often relatively asymptomatic. Branched kidney stone occupying the renal pelvis and at least one calyceal system. Manifest as infection and hematuria. Acute renal failure Asymptomatic bilateral obstruction Solitary Kidney with obstructive stone Location and characteristics of pain from ureteral stones Depends on the level of obstruction and its degree: ureteropelvic junction pelvic brim ureterovesical junction UPJ Stone Stones obstructing the ureteropelvic junction may present with mild-to-severe deep flank pain without radiation to the groin Ureteral Stone Upper ureter Mid Ureter Cause pain that radiates anteriorly and caudally. Can easily mimic appendicitis on the right or acute diverticulitis on the left. Distal Ureter and UVJ stones Cause pain that tends to radiate into the groin or testicle in the male or labia majora in the female At the ureterovesical junction also may cause irritative voiding symptoms mimicking cystitis, such as: urinary frequency dysuria Pain distribution review Bladder Stones Usually asymptomatic and are passed relatively easily during urination. Rarely, a patient reports positional urinary retention (obstruction precipitated by standing, relieved by recumbency). Phases of an attack Phases of an attack Physical exam Physical exam Dramatic costovertebral angle tenderness unremarkable abdominal evaluation painful testicles but normal-appearing constant body positional movements (eg, writhing, pacing) Tachycardia Hypertension Microscopic hematuria Diagnosis Diagnosis The diagnosis of nephrolithiasis is often made on the basis of clinical symptoms alone, although confirmatory tests are usually performed. Laboratory tests Labarotary Testing The recommended based on EUA recommendations: Urinary sediment/dipstick test: To demonstrate blood cells Serum creatinine level: To measure renal function Additional Lab Tests May be helpful: CBC in febrile patients Serum electrolyte assessment in vomiting patients 24-Hour urine profile on outpatient basis Imaging studies Imaging studies Noncontrast abdominopelvic CT scan: The imaging modality of choice for assessment of urinary tract disease, especially acute renal colic. IV contrast and delayed images might be required in selected cases Imaging studies Renal ultrasonography: Renal stone Hydronephrosis or ureteral dilation Misses 30 % of stones Plain abdominal radiograph (flat plate or KUB) misses 40 % of stones Imaging studies Management Emergency Renal Colic IV access to allow : Fluid Analgesics: Paracetamol NSAID Opiod Antiemetic In case of infection: Urine culture Blood culture accordingly e.g. febrile Antibiotics Approach Considerations In emergency settings what should be kept in mind is the small percentage suffering renal damage or sepsis. These include: Evident infection with obstruction A solitary functional kidney Bilateral ureteral obstruction Renal failure Important The most morbid and potentially dangerous aspect of stone disease is the combination of urinary tract obstruction and upper urinary tract infection. Pyelonephritis Pyonephrosis Urosepsis Early recognition and immediate surgical drainage are necessary in these situations Approach Considerations The size of the stone is an important predictor of spontaneous passage. A stone less than 4 mm in diameter has an 80% chance of spontaneous passage; this falls to 20% for stones larger than 8 mm in diameter Approach Considerations Hospital admission is clearly necessary when any of the following is present: Oral analgesics are insufficient to manage the pain. Intractable vommiting Ureteral obstruction from a stone occurs in a solitary or transplanted kidney. Bilateral ureteral obstruction Ureteral obstruction from a stone occurs in the presence of a urinary tract infection (UTI) Fever Sepsis Pyonephrosis Approach Considerations Relative indications to consider for a possible admission include comorbid conditions diabetes dehydration renal failure immunocompromised state perinephric urine extravasation pregnancy Clinic Follow up Patients who do not meet admission criteria to be discharged on medical expulsive therapy from the ED in anticipation that the stone will pass spontaneously at home. Arrangements should be made for follow-up with a urologist in 2-3 days. Active medical expulsive therapy Paracetamol PRN for pain with or without Codeine NSAID PRN for pain Oral opiod analogue for severe pain Alpha blockers Antiemetic PRN for nausea and/or vommiting Prednisone 20 mg twice daily for 6 days With MET, stones 5-8 mm in size often pass, especially if located in the distal ureter. Approach Considerations General recommendation not to wait longer than 4 weeks for a stone to pass spontaneously before considering intervention. Approach Considerations About 15-20% of patients require invasive intervention eventually as emergency or electively due to: stone size continued obstruction Infection intractable pain Indications for Surgery The primary indications for surgical treatment include: Pain Infection Obstruction Indications for urgent intervention: Obstruction complicated by evident infection Obstruction complicated by acute renal failure Solitary kidney Bilateral obstruction Surgical options Obstruction relief: Ureteral stent insertion Percutaneous nephrostomy Definitive surgical treatment: ESWL Ureteroscopy PCNL Open, laparoscopic and robotic pyelo-lithotomy, ureterolithotomy, cystolithotomy Open anatrophic nephrolithotomy Surgical options For an obstructed and infected collecting system secondary to stone disease Emergency surgical relief is required with no contraindications: percutaneous nephrostomy for critical patients ureteral stent placement for stable patients Surgical options The vast majority of symptomatic urinary tract calculi are now treated with noninvasive or minimally invasive techniques Open surgical excision of a stone from the urinary tract is now limited to isolated atypical cases Surgical options ESWL and ureteroscopy are internationaly recognized as first-line treatments for ureteral stones. The 2005 American Urological Association (AUA) staghorn calculus guidelines recommend percutaneous nephrostolithotomy as the cornerstone for management Ureteral Stent Guarantees drainage of urine from the kidney into the bladder and bypass any obstruction. Relieves renal colic pain even if the actual stone remains. Dilate the ureter, making ureteroscopy and other endoscopic surgical procedures easier to perform later. Percutaneous nephrostomy Indicated if stent placement is inadvisable or impossible. In particular patients with pyonephrosis who have a UTI or urosepsis exacerbated by an obstructing calculus Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy ESWL, the least invasive of the surgical methods of stone removal Utilizes an underwater energy wave focused on the stone to shatter it into passable fragments It is especially suitable for stones that are smaller than 2 cm and lodged in the upper or middle calyx the upper ureter Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy The patient, under varying degrees of anesthesia The shock head delivers shockwaves developed from an Electrohydraulic Electromagnetic piezoelectric source Ureteroscopy Ureteroscopic manipulation of a stone is a commonly applied method of stone removal A small endoscope, which may be Rigid Semirigid Flexible is passed into the bladder and up the ureter to directly visualize the stone Ureteroscopy Flexible ureteroscopy allows tackling of even lower calyceal stones Stones are fragmented using Swiss lithoclast Laser Ultrasonic lithotripter Stones are retrieved using a stone basket Percutaneous nephrostolithotomy Percutaneous procedures are generally reserved for large and/or complex renal stones and failures from the other 2 modalities Percutaneous nephrostolithotomy is especially useful for stones larger than 2 cm in diameter Percutaneous nephrostolithotomy In some cases, a combination of SWL and a percutaneous technique is necessary to completely remove all stone material from a kidney. Open Surgery Open surgery has been used less and less often since the development of the previously mentioned techniques It now constitutes less than 1% of all interventions. Disadvantages include longer hospitalization increased requirements for blood transfusion. Long-Term Monitoring Metabolic evaluation is done by a typical 24-hour urine determination of: urinary volume pH specific gravity Calcium Citrate Magnesium Oxalate Phosphate uric acid. Long-Term Monitoring Most common findings are Hypercalciuria Hyperuricosuria Hyperoxaluria Hypocitraturia low urinary volume Chemoprophylaxis Chemoprophylaxis of uric acid and cystine calculi consists primarily of long-term alkalinization of urine. Chemoprophylaxis Chemoprophylaxis Pharmaceuticals that can bind free cystine in the urine: D-penicillamine 2-alpha-mercaptopropionyl-glycine Help reduce stone formation in cystinuria. Captopril has been shown to be effective in some trials Dietary Measures In almost all patients in whom stones form, an increase in fluid intake and, therefore, an increase in urine output is recommended. This is likely the single most important aspect of stone prophylaxis The goal is a total urine volume in 24 hours in excess of 2 liters. Dietary Measures The only other general dietary guidelines are to avoid excessive salt and protein intake. Moderation of calcium and oxalate intake is also reasonable Beware to advice moderation not avoid calcium intake as it will result in calcium deficiency disorders, most importantly osteoperosis. Thank you References • • •