Anesthesia Considerations for Simultaneous Pancreas

ANESTHESIA CONSIDERATIONS

FOR SIMULTANEOUS PANCREAS-

KIDNEY TRANSPLANTATION

AND

POST-REPERFUSION SYNDROME:

A CASE REPORT AND REVIEW OF THE

LITERATURE

Christopher J. Patton, BSN

Barnes-Jewish College

CASE STUDY

REPEAT SPKT

• 43-year-old, ASA 3, 47 kg female

• Underwent primary SPKT two years earlier

– Pancreatic graft failure due to severe pancreatitis

– Renal graft failure secondary to rejection

• History: IDDM, ESRD, Anemia, GERD, HTN, HLD

• Anesthesia History: Unremarkable

• Allergy: Cephalexin (rash)

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

• Airway: Mallampati III, TM distance = 5 cm, normal cervical extension

• Hypertensive: MAP 100 - 125 mm Hg

• ECG: NSR with poor R-wave progression

• Negative nuclear stress test

• TTE: Normal EF, mild LVH/LAE, trace MR/TR

• CXR: Remarkable only for an in situ left subclavian

HD catheter with its tip at the atriocaval junction

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

• Lungs CTA bilaterally

• Normal heart tones

• No carotid bruits

• Labs:

– Elevated Cr and PO

4

(4.43/6.0 mg/dL, respectively)

– Decreased H & H (9.9/28.8 g/dL)

• Severe N/V: three episodes of emesis in the holding area

– Treated with transdermal scopolamine, two doses of odansetron, famotidine, and metoclopramide

• Midazolam 2 mg administered prior to leaving holding

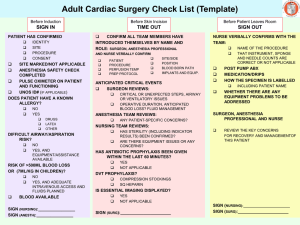

INDUCTION

MAINTENANCE OF

ANESTHESIA

•

Desflurane titrated between 4.2-6.5 %

•

NMB maintained with atracurium

•

Serum glucose assessed Q30 minutes

•

Regular insulin administered IV in small doses throughout the case as directed by surgeon

IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE THERAPY

• Induced with methylprednisolone 350 mg IV (15 min)

• Followed by infusion of anti-thymocyte globulin

• Infusion rate halved after hypotension noted

• Small boluses of phenylephrine, calcium chloride and ephedrine to maintain MAP ~ 80 mm Hg

• BP stabilizes with 1.5 L of 0.9% NS, 250 mL of 5% albumin, and dopamine infusion at 5 g/kg/min

WE’RE CRUISING…

• Prepare for pancreas graft insertion

– Heparin 3,000 units

– Mannitol 12.5 g

• Graft inserted

• Vascular anastamoses completed

• Surgeon announces venous clamp will be released

• Student experiences SEVERE pudendal neuropathy as this happens……

PANCREATIC REPEFUSION

OVER THE NEXT 80 MINUTES…

• Norepinephrine infusion titrated to 0.25 g/kg/min

• Six 64 g boluses of norepinephrine were administered

• 2L NS bolused to maintain a MAP > 60 mm Hg

– Recall, goal MAP ~80 mm Hg

• Diphenhydramine (25 mg) and esmolol (10 mg) administered

• No observed response

• Heart rate remained 120 – 140 bpm

• Four hours into the case, MAP stabilized at 70 mm Hg

• Heparin and mannitol administered prior to vascular clamping and reperfusion of renal graft

• Anesthesia grimaces….

RENAL GRAFT REPEFUSION

• MAP acutely fell from 72 to 51 mm Hg after reperfusion

• 128 g norepinephrine bolus administered

• Second unit of PRBCs transfused

• 10 mg furosemide administered, per the surgeon’s request

• CardioQ SV monitor utilized to assess volume status

• 4.5 L of crystalloid infused over remainder of case,

• Fluid total: 8 L crystalloid and ~ 1.5 L colloid

• Estimated blood loss was 500 mL

• A total of three ampules of sodium bicarbonate were administered to correct acidosis

POST-REPERFUSION SYNDROME

EMERGENCE

• By the end of the case, hemodynamics stabilized

– Norepinephrine infusion decreased to 0.08 g/kg/min

– Dopamine infusion discontinued

– Anti-thymocyte globulin infusion reinitiated at full dose

• NMB antagonized with 0.5 mg glycopyrrolate and 3.5 mg neostigmine after surgical incision closed (fascia left open)

• Patient awoke and followed commands, but was determined to be too weak to safely extubate

• Propofol infusion initiated and patient transported to ICU in stable condition

POSTOPERATIVE COURSE

• Patient was extubated the following morning and transferred out of the ICU two days later

• Patient back to OR for closure of fascia POD 8

– Wound infection and edematous pancreas with multiple necrotic areas discovered

• Returned to OR on POD 12 for I&D and closure of the fascia and skin

• Patient remained hospitalized for one month prior to being discharged to a rehabilitation facility

DISCUSSION

WHO BENEFITS FROM SPKT?

• Patients with brittle diabetes and ESRD

• ~ 50-60% of insulin-dependent diabetics develop diabetic nephropathy

• Leading cause of renal failure requiring hemodialysis in young and middle-aged adults in the United States

• While pancreatic transplantation may be indicated for the treatment of disease states such as pancreatitis or cancer, an overwhelming 96% of the total pancreatic transplants in the US are performed in patients with underlying IDDM

(Lin, 2007; Yost & Niemann, 2010; Gruessner, 2011)

SPKT VS. PTA & PAK

(Gruessner, 2011)

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN SPKT FAILS?

• Uncommon

• Serious

• Few institutions with much experience

(Gruessner, 2011)

PANCREATIC

ANASTAMOSES

During bench preparation of pancreatic graft, the bifurcation of donor’s Iliac

A. is anastamosed with the

Superior Messenteric A. &

Splenic A. from graft for ease of anastamosis to recipient’s R Common Iliac

A. during transplantation

RENAL ANASTAMOSES

ACS Surgery Principles and Practice

ANESTHESIA CONSIDERATIONS

• Preoperative Assessment, Planning & Collaboration

• Minimizing Consequences of IDDM and ESRD

• Glycemic Control

• Autonomic Neuropathy

• Renal pharmacological considerations

• Management of Immunosuppressive Therapy

• Optimization of Graft Function

• Fluid Management

• Commonly Utilized Intraoperative Drugs

• Adequate Graft Perfusion

• Management of Post-Reperfusion Syndrome (PRS)

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

• Begins with a review of the health history

• Special attention to co-existing diseases that often accompany ESRD and IDDM:

• Hypertension, anemia, uremia, and cardiac disease

• Cardiac workup warranted due to risk for silent ischemia secondary to autonomic neuropathy

• Coronary angiography vs. non-invasive testing such as

EKG, TTE, Nuclear Stress Testing, etc

(Garwood, 2008; Evenson & Fryer, 2009; Ouellette, 2010; De Lima, et al., 2003)

PREOPERATIVE LABS

• Laboratory tests should include: CBC, CMP, hemoglobin A

1C

, coagulation studies, and T&C for at least two units of washed PRBCs

• The transplant workup will also include screening tests for a multitude of infectious diseases, as well as ABO and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) compatibility

(Busque, 2009; Ouellette, 2010)

PREOPERATIVE EXAM

• Primary concerns: cardiopulmonary system and airway

• Orthostatics and dialysis details facilitate estimation of blood volume status

• Difficult airway?

– Few studies propose intubation difficult in diabetics

– Subsequent studies did not substantiate these fears

– Nonetheless, prudent to assess joint mobility in neck and jaw and to prepare for difficult visualization of laryngeal structures

• Identify HD shunts/fistulas and verify adequate padding, as pressure may cause thrombosis

(Yost & Niemann, 2010; Garwood, 2008; Busque, 2009; Palmer, 2010)

GLYCEMIC CONTROL

• Many proposed management strategies

• Most authors agree BG should be assessed at least Q30-60 min

• Treat with regular insulin IVP or via continuous infusion

• Mitigates risk for ketoacidosis, depressed immune function, decreased wound healing, and worsened neurologic insult in the setting of cerebral ischemia

• Keep BG > 150 mg/dL prior to pancreatic graft insertion

• Serum glucose decreases ~ 50 mg/dL/hr after reperfusion

• Hypoglycemia difficult to detect due to anesthesia and diabetic and renal disease-related neuropathy

• Another complicating factor is routine administration of high-dose corticosteroid for immunosuppressive therapy

(Yost & Niemann, 2010; Csete & Glas, 2009; Busque, 2009; Palmer, 2010)

ANESTHETIC TECHNIQUE

• Regional anesthesia has been successfully used for isolated pancreas and kidney transplants

• Most authors encourage general endotracheal anesthesia for the following reasons:

– The long, tedious nature of these surgeries

– The benefit of muscle relaxation

– The potential for hemodynamic instability

• Furthermore, splanchnic perfusion to the transplanted organs is a major concern and the sympatholytic effect of regional anesthesia may pose a danger to adequate graft perfusion

(Hadimioglu, Ertug, Bigat, Yilmaz, & Yegin, 2005; Pichel & Macnab, 2005; Busque et al., 2009; Csete & Glas, 2009; Palmer, 2010; Yost & Niemann, 2010).

IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE THERAPY

• Transplant function dependent on immunosuppression

• Induction Agents: Started at time of transplantation

• May continue for a few doses while maintenance agents initiated

• Maintenance Agents: Will be continued indefinitely

• Commonly encountered induction regimens include either monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies which may or may not be supplemented with a large dose of corticosteroid

• Regimens vary between patients and institutions

• Imperative that anesthetist clarifies schedule and dosing with transplant team

(Csete & Glas, 2009; Evenson & Fryer, 2009; Kaufmann et al., 2002)

SIDE EFFECTS

Clinical Anesthesia, 6 th ed., 2009 Miller’s Anesthesia, 7 th ed., 2010

AUTONOMIC NEUROPATHY

• Diabetics, especially those with ESRD, prone to autonomic neuropathy that may cause:

– Gastroparesis increases risk for aspiration

– Cardiovascular lability: possible intraoperative hypotension requiring pressors, dysrhythmias, and bradycardia resistant to atropine

• Regardless of volume status, patients with

ESRD often experience exaggerated hypotension with induction of anesthesia

INDUCTION OF ANESTHESIA

• No standard induction drugs specifically contraindicated

• May require increased dose of propofol

• Titration better than large single bolus

• All patients presenting for SPKT should be considered at risk for aspiration

– RSI with cricoid pressure and slight reverse trendelenberg positioning indicated

NEUROMUSCULAR BLOCKADE

• Succinylcholine usually safe in patients with ESRD

• Serum potassium should be < 5.5 mEq/L

• 0.6 mEq/L increase in potassium after intubating dose

• Increased risk for patients with motor and sensory neuropathy

• Alternative to succinylcholine for RSI is rocuronium

• All short and intermediate acting NDNMBs safe with careful titration based upon TOF monitoring

• Cisatracurium and atracurium ideal due to extrarenal metabolism via Hoffman degredation and plasma cholinesterase

• Primary metabolite, laudanosine, may cause seizures via stimulation of CNS at high plasma concentrations

(Busque et al., 2009; Csete & Glas, 2009; Palmer, 2010; Yost & Niemann, 2010; Ouellette, 2010; Ma & Zhuang, 2002 )

MAINTENANCE OF ANESTHESIA

• Balanced anesthetic technique likely best method to sustain hemodynamic stability

• Drugs selected based upon known side effects

• N

2

O often omitted

• Morphine and meperidine should also be avoided due to the action of their metabolites

• Desflurane and isoflurane are commonly used

• While the metabolism of sevoflurane has been implicated in nephrotoxicity, there is a lack of evidence clearly substantiating these concerns

(Yost & Niemann, 2010; Garwood, 2008)

FLUID CHOICES

• Multiple considerations

• Electrolyte Balance

• Edema/Third-Spacing

• Acid-Base Balance

• Which Crystalloid?

• NS vs. LR vs. Plasmalyte?

• NS widely used, but LR and Plasmalyte may be better

• Which Colloid?

• Albumin vs. HES Solutions?

• Albumin demonstrated to be best colloid

(O'Malley, Frumento, & Bennett-Guerrero, 2002; Csete & Glas, 2009; Garwood, 2008; Ouellette, 2010; O'Malley et al., 2005; Hadimioglu et al., 2008; Groeneveld, Navickis, & Wilkes, 2011)

MONITORING

• Standard ASA monitors placed upon entering OR

• HD catheters may be used if CVC access warranted

– CVP 10 – 15 mm Hg optimizes CO/Renal Blood Flow

• Pulmonary Artery Catheter based upon H&P

– Higher filling pressures (>20/15 mm Hg) indicative of better graft function than lower pressures in one study

• A-Line based upon H&P

• Non-invasive cardiac stroke volume monitors

– These have been found to facilitate goal directed fluid therapy

– Demonstrated to PONV, morbidity, and hospital stay

(Yost & Niemann, 2010; Csete & Glas, 2009; Busque, 2009; Bundgaard-Nielsen, 2007; Benes et al., 2010)

INTRAOPERATIVE HEMODYNAMICS

• Major hemodynamic shifts are common during organ transplantation

• One illustration of these hemodynamic shifts was provided by a large series that found substantial changes in intraoperative hemodynamics, with hypotension more likely than hypertension (49.6% vs. 26.8%)

(Csete & Glas, 2009)

SPKT HEMODYNAMICS

• Another study following 17 patients presenting for SPKT reported similar hemodynamic shifts

(Mazza, et al., 1998)

POST-REPERFUSION SYNDROME

• PRS was first described by Aggarwal (1987), in the context of orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT)

• A systemic phenomenon generally defined as a 30% decrease in MAP, sustained > 1 minute, occurring < 5 minutes after organ reperfusion

• PRS has been reported in surgeries other than OLT

• Cardiopulmonary bypass, aneurysm repair, ischemic limb reperfusion, and intestinal and renal transplants

• Literature describing incidence of PRS is inconsistent, with rates between 20-55% of all OLT patients and 4% of renal transplants reported

(Bruhl et al., 2012; Chung et al., 2012; Fukazawa & Pretto, 2011; Lomax, Klucniks, & Griffiths, 2010)

PRS PHYSIOLOGY

• While the exact mechanism of PRS remains controversial, some of the initially proposed causes included:

• Cold preservation solution into systemic circulation

• Acid-base and electrolyte derangements

• Release of pro-inflammatory mediators, including nitric oxide

(NO), due to massive induction of oxidative stress

• However, one prospective study found no statistical correlation between serum pH, core temperature, potassium and calcium levels, or arterial blood-gas tensions and PRS

• In the same study, a decreased SVR was the only variable that correlated significantly with PRS

(Bruhl et al., 2012; Chung et al., 2012; Fukazawa & Pretto, 2011; Lomax, Klucniks, & Griffiths, 2010)

PRS PHYSIOLOGY CONTINUED

• Another study exploring PRS hemodynamics found preload was significantly lower in PRS patients than non-PRS patients; despite equal LV function, as observed by TEE

• Acute vasodilation could explain both the decrease in

SVR and preload

• Possibly mediated by release of vasoactive inflammatory mediators, secondary to an immunogenic response, resulting in a massive extracellular fluid shift

• Supported by another study that identified increased levels of neutrophil and macrophage activation, with simultaneous anaphylatoxin formation, in patients experiencing PRS

• Another proposed mechanism is the release of ROS

(Bruhl, 2012; Yost & Niemann, 2010; Csete & Glas, 2009)

WHY IS PRS IMPORTANT?

• PRS implicated in a number of undesirable outcomes:

• Longer mechanical ventilation times and ICU stays, poor graft function, acute organ dysfunction unrelated to the surgical site, and increased mortality

• Bruhl reported a 10% increase in graft failure at six in renal transplant patients experiencing PRS

• The number of post-transplant hospitalization days was almost twice that of non-PRS patients who had the same surgery

• Another study, following OLT patients who developed PRS, reported the relative risk of severe kidney dysfunction to be over three times greater that the non-PRS group

• More frightening, the relative risk of death was determined to be almost three times greater than non-PRS cohorts

(Bruhl, 2012)

WHO IS AT RISK FOR PRS?

A significant correlation was identified between

PRS and patients who were either diabetic,

Asian, older than 60, or transplanted with an organ from an extended criteria donor

(Bruhl, 2012)

PRS & AUTONOMIC DYSFUNCTION

• Increased prevalence of PRS in patients with autonomic dysfunction

• Both IDDM and ESRD are associated with autonomic dysfunction

• Thus, these pathologies may be good markers for predicting PRS in surgical patients.

(Perez-Pena, et al., 2003)

PRS TREATMENTS?

• Unfortunately, there does not yet appear to be a consensus in the literature regarding effective treatment regimens for PRS

• Proposed strategies include:

• Methylene Blue to inhibit inducible NO synthase and scavenge NO

• On retrospective study of 700 patients found methylene blue to have no effect on changes in MAP, vasopressor or blood transfusion requirements, or end-organ effects

• Prophylactic administration of epinephrine and atropine to attenuate hypotension and bradycardia

• Mannitol to scavenge ROS

– Sodium bicarbonate to buffer the increased acid load

• Nonetheless, despite 25 years of research, there remains much to learn about PRS

• However, as more definitive explanations of the mechanism and treatment of PRS emerge, it is reasonable to expect outcomes for a number of surgical procedures to improve

(Bruhl et al., 2012; Busque et al., 2009; Chung et al., 2012; Csete & Glas, 2009; Fukazawa & Pretto, 2011; Ouellette, 2010; Palmer, 2010; Yost & Niemann, 2010)

HINDSIGHT IS

20/20

AREAS FOR IMPROVEMENT

• More proactive/aggressive treatment of N/V

• Haldol/droperidol, diphenhydramine, etc

• Tighter glycemic control

• Continuous insulin infusion

• Earlier utilization of SV Monitor

• Aggressive treatment of early PRS with Epi?

• Fluid Selection

• LR only or more balanced ratio of LR/NS

THANK YOU!

QUESTIONS?

pattonc@anest.wustl.edu

REFERENCES

Benes, J., Chytra, I., Altmann, P., Hluchy, M., Kasal, E., Svitak, R., . . . Stepan, M. (2010). Intraoperative fluid optimization using stroke volume variation in high risk surgical patients: results of prospective randomized study. Crit Care,

14(3), R118. doi: 10.1186/cc9070

Bruhl, S. R., Vetteth, S., Rees, M., Grubb, B. P., & Khouri, S. J. (2012). Post-reperfusion Syndrome during Renal

Transplantation: A Retrospective Study. Int J Med Sci, 9(5), 391-396. doi: 10.7150/ijms.4468

Busque, S., L., M. M., Desai, D. M., Esquivel, C. O., Angelotti, T., & Lemmens, H. J. M. (2009). Liver/kidney/pancreas transplantation. In R. A. Jaffe & S. I. Samuels (Eds.), Anesthesiologist's manual of surgical procedures (4th ed., pp. 679-

712). Philadelphia, PA: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins.

Cannesson, M., Pestel, G., Ricks, C., Hoeft, A., & Perel, A. (2011). Hemodynamic monitoring and management in patients undergoing high risk surgery: a survey among North American and European anesthesiologists. Crit Care, 15(4),

R197. doi: 10.1186/cc10364

Chung, I. S., Kim, H. Y., Shin, Y. H., Ko, J. S., Gwak, M. S., Sim, W. S., . . . Lee, S. K. (2012). Incidence and predictors of post-reperfusion syndrome in living donor liver transplantation. Clin Transplant, 26(4), 539-543. doi:

10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01568.x

Csete, M., & Glas, K. (2009). Transplant anesthesia. In P. G. Barash, B. F. Cullen, R. K. Stoelting, M. K. Calahan & M. C.

Stock (Eds.), Clinical anesthesia (6th ed., pp. 1375-1392). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Dart, A. B., Mutter, T. C., Ruth, C. A., & Taback, S. P. (2010). Hydroxyethyl starch (HES) versus other fluid therapies: effects on kidney function. Cochrane Database Syst Rev(1), CD007594. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007594.pub2

Davidson, I. J. (2006). Renal impact of fluid management with colloids: a comparative review. Eur J Anaesthesiol, 23(9), 721-

738. doi: 10.1017/S0265021506000639

De Lima, J. J. G., Sabbaga, E., Vieira, M. L. C., de Paula, F. J., Ianhez, L. E., Krieger, E. M., & Ramires, J. A. F. (2003).

Coronary Angiography Is the Best Predictor of Events in Renal Transplant Candidates Compared With

Noninvasive Testing. Hypertension, 42(3), 263-268. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000087889.60760.87

Evenson, A. R. (2009). Transplantation for the general surgeon. In S. Ashley & D. W. Wilmore (Eds.), ACS Surgery:

Principles and Practice (pp. 1-20). Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker.

Fukazawa, K., & Pretto, E. A. (2011). The effect of methylene blue during orthotopic liver transplantation on post reperfusion syndrome and postoperative graft function. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci, 18(3), 406-413. doi:

10.1007/s00534-010-0344-7

Garwood, S. (2008). Renal disease. In R. L. Hines & K. E. Marschall (Eds.), Stoelting's anesthesia and co-existing disease (5th ed., pp. 323-348). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone.

Groeneveld, A. B., Navickis, R. J., & Wilkes, M. M. (2011). Update on the comparative safety of colloids: a systematic review of clinical studies. Ann Surg, 253(3), 470-483. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318202ff00

Gruessner, A. C. (2011). 2011 update on pancreas transplantation: comprehensive trend analysis of 25,000 cases followed up over the course of twenty-four years at the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR). Rev Diabet Stud, 8(1),

6-16. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2011.8.6

Hadimioglu, N., Ertug, Z., Bigat, Z., Yilmaz, M., & Yegin, A. (2005). A randomized study comparing combined spinal epidural or general anesthesia for renal transplant surgery. Transplant Proc, 37(5), 2020-2022. doi:

10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.03.034

Hadimioglu, N., Saadawy, I., Saglam, T., Ertug, Z., & Dinckan, A. (2008). The effect of different crystalloid solutions on acid-base balance and early kidney function after kidney transplantation. Anesth Analg, 107(1), 264-269. doi:

10.1213/ane.0b013e3181732d64

Hokema, F., Ziganshyna, S., Bartels, M., Pietsch, U. C., Busch, T., Jonas, S., & Kaisers, U. (2011). Is perioperative low molecular weight hydroxyethyl starch infusion a risk factor for delayed graft function in renal transplant recipients?

Nephrol Dial Transplant, 26(10), 3373-3378. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr017

Hunter, K. (2003). Anesthesiology in renal and pancreas transplantation. Current Opinion in Organ Transplantation, 8(3), 243-

248.

Isla Pera, P., Moncho Vasallo, J., Guasch Andreu, O., Ricart Brulles, M., & Torras Rabasa, A. (2012). Impact of simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation: patients' perspectives. Patient Prefer Adherence, 6, 597-603. doi:

10.2147/PPA.S35144

Joyce, A. T., Iacoviello, J. M., Nag, S., Sajjan, S., Jilinskaia, E., Throop, D., . . . Alexander, C. M. (2004). End-stage renal disease-associated managed care costs among patients with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care, 27(12), 2829-2835.

Kaufman, D. B., Leventhal, J. R., Gallon, L. G., Parker, M. A., Elliott, M. D., Gheorghiade, M., . . . Stuart, F. P. (2002).

Technical and immunologic progress in simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation. Surgery, 132(4), 545-553; discussion 553-544.

Lin, L. (2007). Endocrine and nutritional disease. In R. K. Stoelting & R. D. Miller (Eds.), Basics of anesthesia (5th ed., pp. 437-

452). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone.

Lomax, S., Klucniks, A., & Griffiths, J. (2010). Anaesthesia for intestinal transplantation. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia,

Critical Care & Pain. doi: 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkq043

Ma, H., & Zhuang, X. (2002). Selection of neuromuscular blocking agents in patients undergoing renal transplantation under general anesthesia. Chin Med J (Engl), 115(11), 1692-1696.

Mazza, E., De Gasperi, A., Corti, A., Amici, O., Roselli, E., Notaro, P., . . . Santandrea, E. (1998). Hypotension after pancreatic reperfusion during combined kidney-pancreas transplantation. Transplant Proc, 30(2), 265-266.

O'Malley, C. M., Frumento, R. J., & Bennett-Guerrero, E. (2002). Intravenous fluid therapy in renal transplant recipients: results of a US survey. Transplant Proc, 34(8), 3142-3145.

O'Malley, C. M., Frumento, R. J., Hardy, M. A., Benvenisty, A. I., Brentjens, T. E., Mercer, J. S., & Bennett-Guerrero, E.

(2005). A randomized, double-blind comparison of lactated Ringer's solution and 0.9% NaCl during renal transplantation. Anesth Analg, 100(5), 1518-1524, table of contents. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000150939.28904.81

Ouellette, S. M. (2010). Renal anatomy, physiology, pathophysiology, and anesthesia management. In J. J. Nagelhaut & K. L.

Plaus (Eds.), Nurse anesthesia (4th ed., pp. 694-726). St. Louis, MO: Saunders-Elsevier.

Palmer, T. J. (2010). Hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal disturbances and anesthesia. In J. J. Nagelhaut & K. L. Plaus (Eds.),

Nurse anesthesia (4th ed., pp. 727-770). St. Louis, MO: Saunders-Elsevier.

Perez-Pena, J., Rincon, D., Banares, R., Olmedilla, L., Garutti, I., Arnal, D., . . . Clemente, G. (2003). Autonomic neuropathy is associated with hemodynamic instability during human liver transplantation. Transplant Proc, 35(5), 1866-1868.

Pichel, A. C., & Macnab, W. R. (2005). Anaesthesia for pancreas transplantation. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical

Care & Pain, 5(5), 149-152. doi: 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mki040

Pihusch, R., Holler, E., Muhlbayer, D., Gohring, P., Stotzer, O., Pihusch, M., . . . Kolb, H. J. (2002). The impact of antithymocyte globulin on short-term toxicity after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant,

30(6), 347-354. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703640

Rang, S. T., West, N. L., Howard, J., & Cousins, J. (2006). Anaesthesia for Chronic Renal Disease and Renal Transplantation.

EAU-EBU Update Series, 4(6), 246-256. doi: 10.1016/j.eeus.2006.08.005

SarinKapoor, H., Kaur, R., & Kaur, H. (2007). Anaesthesia for renal transplant surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand, 51(10), 1354-

1367. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01447.x

Shrestha, B. M. (2006). Simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation for end-stage renal failure secondary to diabetic nephropathy : principles and practice. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc, 45(163), 323-330.

Sollinger, H. W., Odorico, J. S., Becker, Y. T., D'Alessandro, A. M., & Pirsch, J. D. (2009). One thousand simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants at a single center with 22-year follow-up. Ann Surg, 250(4), 618-630. doi:

10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b76d2b

Vincent, J. L., Rhodes, A., Perel, A., Martin, G. S., Della Rocca, G., Vallet, B., . . . Singer, M. (2011). Clinical review: Update on hemodynamic monitoring--a consensus of 16. Crit Care, 15(4), 229. doi: 10.1186/cc10291

Wall, R. T. I. (2008). Endocrine disease. In R. L. Hines & K. E. Marschall (Eds.), Stoelting's anesthesia and co-existing disease (5th ed., pp. 365-406). Philatelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone.

Yost, C. S., & Niemann, C. U. (2007). Renal, liver, and biliary tract disease. In R. K. Stoelting & R. D. Miller (Eds.), Basics of

anesthesia (5th ed., pp. 425-436). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone.

Yost, C. S., & Niemann, C. U. (2010). Anesthesia for abdominal organ transplantation. In R. D. Miller (Ed.), Miller's anesthesia

(7th ed., pp. 2155-2184). Philadelphis, PA: Churchill Livingstone.