Peripheral Arterial Disease

Education and ABI Training

for Vascular Nurses

Presented by

The Society for Vascular Nursing

Comprehensive In-Service Lecture Kit

Supported by an educational grant from

Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi Partnership

PERIPHERAL ARTERIAL DISEASE

Education and ABI Training for

Vascular Nurses

A Train the Trainer Program

The Ankle Brachial Index:

The Key to Early Detection

and Management of

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Acknowledgements

Course Development

– ABI Registry Task Force

Diane Treat-Jacobson, Ph.D., R.N.

Carolyn Robinson MSN, RN, CNP,CVN

Marge Lovell RN, CCRC, CVN, BEd

Patricia Lewis, MS, FNP, CVN

M. Kate Schmidt, BSN, RN, CVN

Contact Information

Society for Vascular Nursing

203 Washington St., PMB 311

Salem, MA 01970

888-536-4786; 978-744-5005; Fax: 978-744-5029

Peripheral Arterial Disease

and Claudication

Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD)

A disorder caused by atherosclerosis that

limits blood flow to the limbs

Claudication

A symptom of PAD characterized by pain,

aching, or fatigue in working skeletal

muscles. Claudication arises when there is

insufficient blood flow to meet the metabolic

demands in leg muscles of ambulating

patients

New PAD Guidelines

Enhanced quality of patient care

Increased recognition of the importance of

atherosclerotic lower extremity PAD:

– Prevalence

– Cardiovascular risk

– Quality of life

Improved ability to detect and treat renal artery

disease

Improved ability to detect and treat AAA

The evidence base has become increasingly robust,

so that a data-driven care guideline is now possible

Defining a Population “At Risk” for

Lower Extremity PAD

Age less than 50 years with diabetes, and one

additional risk factor (e.g., smoking, dyslipidemia,

hypertension, or hyperhomocysteinemia)

Age 50 to 69 years and history of smoking or diabetes

Age 70 years and older

Leg symptoms with exertion (suggestive of

claudication) or ischemic rest pain

Abnormal lower extremity pulse examination

Known atherosclerotic coronary, carotid, or renal

artery disease

Relative Prevalence of Peripheral

Arterial Disease

Age

(years)

Population

(millions)

PAD

(millions)

Claudication

(millions)

40-59

68.9

2.1

0.9

60-69

19.8

1.6

0.8

70

24.8

4.7

113.5

8.4

2.5

4.2

Criqui MH et al. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:381-6.

Hiatt W et al. Circulation. 1995;91:1472-9.

Porter J. Mod Med. 1987;55:66-75.

US Census Data, 1998 estimates.

Web address www.census.gov/population/estimates/nation/infile2-1.txt

Systemic Manifestations of

Atherosclerosis

• TIA

• Ischemic stroke

• Myocardial Infarction

• Unstable angina pectoris

• Renovascular hypertension

• Erectile dysfunction

• Claudication

• Critical limb ischemia, rest pain,

gangrene, amputation

Prevalence of PAD

NHANES1

Aged >40 years

San

4.3%

Diego2

11.7%

Mean age 66 years

NHANES1

14.5%

Aged 70 years

Rotterdam3

19.1%

Aged >55 years

Diehm4

In a primary care

population defined by age

and common risk factors,

the prevalence of PAD was

approximately one in three

patients

19.8%

Aged 65 years

PARTNERS5

29%

Aged >70 years, or 50–69 years with a history diabetes or smoking

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

NHANES=National Health and Nutrition Examination Study;

PARTNERS=PAD Awareness, Risk, and Treatment: New Resources for Survival [program].

1. Selvin E, Erlinger TP. Circulation. 2004;110:738-743.

2. Criqui MH et al. Circulation. 1985;71:510-515.

3. Diehm C et al. Atherosclerosis. 2004;172:95-105.

4. Meijer WT et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:185-192.

5. Hirsch AT et al. JAMA. 2001;286:1317-1324.

35%

Prevalence of PAD Increases with Age

Rotterdam Study (ABI <0.9)1

San Diego Study (PAD by noninvasive tests)2

Patients With P.A.D. (%)

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

55-59

60-64

65-69

70-74

75-79

80-84

85-89

Age Group,

years

ABI=ankle-brachial index

1. Meijer WT, et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:185-192.

2. Criqui MH, et al. Circulation. 1985;71:510-515.

Gender Differences in the

Prevalence of PAD

18

Prevalence (%)

16

14

12

6880 Consecutive Patients (61% Female)

in 344 Primary Care Offices

Women

Men

10

8

6

4

2

0

<70

70–74

75–79

Age (years)

Diehm C. Atherosclerosis. 2004;172:95-105.

80–74

>85

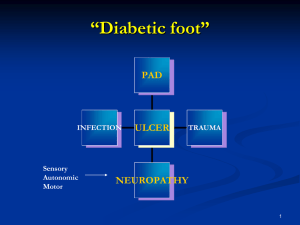

Diabetes Increases Risk of PAD

Prevalence of PAD (%)

25

22.4*

19.9*

20

15

12.5

10

5

0

Normal glucose

tolerance

Impaired glucose

tolerance

Diabetes

Impaired Glucose Tolerance was defined as oral glucose tolerance test value ≥140 mg/dL but <200 mg/dL.

*P.05 vs normal glucose tolerance.

Reprinted with permission from Lee AJ et al. Br J Haematol. 1999;105:648-654. www.blackwell-synergy.com

Ethnicity and PAD:

The San Diego Population Study

% PAD

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

NHW

Black Hispanic Asian

NHW = Non-hispanic white

Criqui et al. Circulation. 2005: 112: 2703-2707.

Risk Factors for PAD

Reduced Increased

Smoking

Diabetes

Hypertension

Hypercholesterolemia

Hyperhomocysteinemia

C-Reactive Protein

Relative Risk

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Hirsch AT, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:e1-e192.

Pathogenesis of

Progressive Atherosclerosis

Risk of Ischemic Events

Previous MI

– 5-7 times more likely to have another MI

– 3-4 times more likely to have a stroke

Previous stroke

– 9 times more likely to have another stroke

– 2-3 times more likely to have an MI

PAD

– 4 times more likely to have an MI

– 2-3 times more likely to have stroke

Long-term Survival in Patients With PAD

100

Survival (%)

Normal subjects

75

Asymptomatic PAD

50

Symptomatic PAD

Severe symptomatic PAD

25

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Year

Criqui MH et al. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:381-386. Copyright © 1992 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Contemporary PAD

Rates of Myocardial Infarction and Death

3649 subjects (average age 64 yrs) followed up for 7.2 years

50

40

%

30

20

10

0

MI

No PAD

Asymptomatic PAD

Death

Symptomatic PAD

Hooi JD, et al. J Clin Epid. 2004;57:294–300.

Association Between ABI and

All-Cause Mortality*

Risk increases at

ABI values below

1.0 and above 1.3

Total mortality (%)

80

70

N=5748

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

<0.61

(n=156)

0.61-0.70 0.71-0.80 0.81-0.90 0.91-1.00 1.01-1.10 1.11-1.20 1.21-1.30 1.31-1.40

(n=141)

(n=186)

(n=310)

(n=709)

(n=1750) (n=1578)

Baseline ABI

Age range=mid- to late-50s; *Median duration of follow-up was 11.1 (0.1–12) years.

Adapted from O’Hare AM et al. Circulation. 2006;113:388-393.

(n= 696)

(n=156)

>1.40

(n=66)

A Risk Factor “Report Card” for all

Individuals with Atherosclerosis

Tobacco smoking

Complete, immediate

cessation

Hypertension

BP less than 130/85

mmHg

Diabetes

Hb A1C <7.0

Dyslipidemia

LDL Cholesterol less than

100 mg/dl

Raise HDL-c

Lower Triglycerides

Inactivity

Follow activity guidelines

Antiplatelet therapy (like aspirin or Plavix) is:

Mandatory

Pathway of Disability in

Intermittent Claudication

PAD

Reduced

muscle

strength

Poor

walking

ability

and IC

Disability

Denervation, muscle-fiber

atrophy, decreased type

II fibers, decreased

oxidative metabolism

Cycle of deconditioning: decreased

HDL, poorer glycemic control,

poorer BP control

Adapted from McDermott M. Am J Med. 1999;CE (I):18-24.

Impact of PAD on Quality of Life

PAD Diagnosis and Management

Symptom Experience

Limitation in Physical Functioning

Limitation in Social Functioning

Compromise of Self

Uncertainty

Adaptation

SF-36 Scores in Health and Disease

Intermittent

claudication

CHF

No. of people

30

Chronic

lung

disease

34 36 38

40

Average

adult

50

Physical Component Summary Score

Average

well adult

55

Location of Obstruction

Influences Symptoms

Obstruction in:

Aorta or

iliac artery

Claudication in:

Buttock, hip,

thigh

Femoral artery

or branches

Thigh,

calf

Popliteal

artery

Calf, ankle,

foot

Claudication: A Symptom of

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Exertional aching pain, cramping, tightness,

fatigue

Occurs in muscle groups, not joints (buttocks,

hips, legs, calves)

Reproducible from one day to the next on

similar terrain

Resolves completely with rest

Occurs again at the same distance once

activity has been resumed

Symptoms in PAD

Patients with

PAD

Symptomatic

PAD

~39%1

Typical Symptoms

(Intermittent

Claudication)

~9%

1.

2.

Asymptomatic

PAD

~61%1

Atypical

Symptoms

~91%

American Heart Association. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2005 Update. 2005.

Hirsch AT, et al. JAMA. 2001;286:1317-1324.

Clinical Assessment of

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Components of Clinical

Assessment

Complete history

– Risk factor assessment

– Activity assessment

Review of medications

Physical examination

– Inspection of lower extremities

– Pulse exam

Questions for Patients

Do you develop discomfort in your legs

when you walk?

– Cramping, aching, fatigue

Do you get this pain when you are sitting

standing, or lying?

Do symptoms only start when you walk?

Does the discomfort always occur at about

the same distance?

Do symptoms resolve once you stop

walking?

PAD Pulse Evaluation

Right

Left

Femoral

Popliteal

Dorsalis pedis

Posterior tibial

Ankle–brachial

index

Note: 0-4 scale, where 0 = absent, 2 = Diminished, 4 = Normal Limits

The Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI)

The first diagnostic assessment that

should be done to evaluate a patient for

PAD after a pulse exam in the presence of

risk factors or if claudication is suspected.

Inexpensive, accurate and can be done in

the primary care setting

The ABI is 95% sensitive and 99% specific

for PAD

Predicts limb survival, potential for wound

healing, and mortality

The Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI)

Indicated

– In the absence of palpable pulses,

or if pulses are diminished

– In the presence or suspicion of

claudication, foot pain at rest, or a

non-healing foot ulcer

– Age greater than 70 years of age,

>50 years with risk factors

(diabetes, smoking)

Concept of ABI

The systolic blood pressure in the leg should be

approximately the same as the systolic blood pressure

in the arm.

Therefore, the

ratio of systolic

blood pressure in

the leg vs the arm

should be

approximately 1

or slightly higher.

Leg pressure

÷

Arm pressure

ABI has been found to be 95% sensitive and 99%

specific for angiographically diagnosed PAD.

Adapted from Weitz JI, et al. Circulation. 1996;94:3026-3049.

≈1

Understanding the ABI

Performed with patient resting in

supine position

All pressures are measured with a

arterial Doppler and appropriately

sized blood pressure cuff

Both brachial pressures are measured

Ankle pressures are measured using

the posterior tibial and/or dorsalis

pedis arteries

Measuring the Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI)

Step 1: Gather Equipment Needed

Equipment needed:

1. Blood Pressure

Cuff

2. Hand-held 5-10

MHz Doppler

probe

3. Ultrasound Gel

American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2003: 26; 3333–3341.

Measuring the Ankle-Brachial Index

(ABI)

Step 2: Position the Patient

Place patient

in supine

position for

5 – 10 minutes

minutes

American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2003: 26; 3333–3341.

Measuring the Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI)

Step 3: Measure the Brachial Blood

Pressure

1. Place the blood pressure cuff

on the arm above the elbow.

2. Apply gel to the skin surface.

3. Place the Doppler probe over

the brachial pulse

4. Inflate the cuff to approx. 20

mm/hg above the point where

systolic sounds are no longer

heard.

5. Deflate the cuff slowly until

the arterial signal returns

(systolic pressure)

6. Repeat in the other arm

American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2003: 26; 3333–3341.

Measuring the Ankle-Brachial Index

(ABI)

Step 4: Position the Cuff Above the Ankle

Place blood

pressure cuff

just above the

ankle of one leg,

apply gel over

the area of the

dorsalis pedis

artery

Dormandy JA et al. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:S1-S296.

Measuring the Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI)

Step 5: Measure the Pressure in the Dorsalis

Pedis Artery

1. Place Doppler probe

over the dorsalis

pedis artery; inflate

the cuff

2. Deflate the cuff; when

the return of blood

flow is detected,

record this as the

systolic pressure of

the DP artery of that

leg

Dormandy JA et al. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:S1-S296.

Measuring the Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI)

Step 6: Measure the Pressure in the

Posterior Tibial Artery

1. Place gel and

Doppler probe over

the posterior tibial

artery (below the

cuff)

2. Measure the

pressure, record as

posterior tibial

pressure for that

leg

Dormandy JA et al. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:S1-S296.

Measuring the Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI)

Step 7: Repeat the Process in the

Opposite Leg

Repeat the same

process in the

other leg and

record the

pressures of the

dorsalis pedis

and posterior

tibial arteries

Dormandy JA et al. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:S1-S296.

Calculating the ABI

Right Leg ABI

Left Leg ABI

Higher right-ankle

pressure

(DP or PT pulse)

=

Higher arm pressure

(of either arm)

Higher left-ankle pressure

(DP or PT pulse)

=

Higher arm pressure

(of either arm)

ABI Interpretation

≤ 0.90 is diagnostic of peripheral arterial

disease

Hiatt WR. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1608-1621.

Calculating the ABI

Example Calculation

Right Leg ABI

=

Left Leg ABI

60 mm Hg

120 mm Hg

Hiatt WR. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1608-1621.

66 mm Hg

=

120 mm Hg

Calculating the ABI

Example Calculation

Right Leg ABI

60 mm Hg

Left Leg ABI

66 mm Hg

= 0.50

120 mm Hg

120 mm Hg

= 0.55

ABI Interpretation

≤ 0.90 is diagnostic of peripheral arterial

disease

Hiatt WR. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1608-1621.

ABI Limitations

Possible false negatives in patients with

noncompressible arteries, such as some

diabetics and elderly individuals

Insensitive to very mild occlusive disease

and iliac occlusive disease

Not well correlated with functional ability

and should be considered in conjunction

with activity history or questionnaires

Interpreting the

Ankle–Brachial Index

ABI

0.90–1.30

Interpretation

Normal

0.70–0.89

Mild

0.40–0.69

Moderate

0.40

Severe

>1.30

Noncompressible

vessels

Adapted from Hirsch AT. Family Practice Recertification. 2000;22:6-12.

Referring to the Vascular Lab

Caveats for referral to vascular lab

• Assessment of the location and severity is

desired

• Patients with poorly compressible vessels

• Normal ABI where there is high suspicion of

PAD

Vascular Lab Evaluation

• Segmental pressures

• Pulse volume recordings

• Treadmill

PAD Diagnosis

Indications for Referral

for Vascular Specialty Care

Lifestyle-disabling

claudication (refractory to

exercise or pharmacotherapy)

Rest pain

Tissue loss

Severity

of

ischemia

Summary

PAD is a common atherosclerotic disease

associated with risk of cardiovascular ischemic

events and significant functional disability

PAD can be effectively assessed in the primary

care setting by primary care nurses

The ankle brachial index is an effective and

efficient measurement tool for diagnosis of PAD

Early detection of PAD allows for appropriate

disease management and decreased likelihood of

ischemic events and disease progression

The Graying of U.S. Society

Seniors 12.4 percent of the

population

Baby boomers will number 75 million

2030

– 20 percent will be over age 65

– 1/2 population > age 40

Nurse Competence in Aging

Imperatives

Moving to an aging society

85+ population > 8.9 million in 2030

Older adults

– Utilize 50% of hospital days

– 45% of the direct care

– primary patient population of most

specialty nurses.

Geriatric preparation significantly

improve health care to older adults.

Classifying the Elderly

ages 65 to 74 - the young old

ages 75 to 84 - the middle old

ages 85 and older - the old old

Impact of Aging

↑risk of health

↑co-morbidities

↑ disabilities

↑dementia

↑seniors with chronic illness requiring

care

↓quality of life

Age Related Changes

Cardiac

Pulmonary

Renal

Gastrointestinal

CNS

Integument

Cardiac Function

Coronary artery blood flow

– decreases 35% between ages 20 and 60.

Cardiac output decreases

Systolic and diastolic murmurs

There is a decrease in cardiac

responsiveness rate with exercise.

Cardiovascular Function and

Aging

Central and peripheral circulation decreases

Aerobic capacity decreases about 1% per

year

Maximum heart rate decreases about 1 beat

per year

Maximum stroke volume decreases

Maximum cardiac output decreases

Peripheral blood flow decreases

Physiological Changes to the

Body with Aging

Heart muscle

– Contractile strength and efficiency decreases

– Left ventricular wall thickens

Heart valves

– fibrotic and sclerotic

SA node and AV tracts

– Infiltrated by fibrous tissue.

Aortic and mitral valves

– Calcify

Changes in Blood Vessels

Veins and arteries

– dilate and stretch

– decreased strength and elasticity.

Peripheral arteries

– Tortuous

– Less resilient.

Aorta and large arteries

– stiffen

Aorta

– may lengthen and become tortuous.

Blood Pressure Changes

Systolic blood pressure

– May rise disproportionately higher than

diastolic.

Changes in the cardiovascular system

– Direct effects on other organs.

Hypertension

– Atherosclerotic changes in blood vessels

– May result in the loss of vision, renal

Strength Changes With Aging

Maximal strength decreases

Muscle mass decreases

Total number and size of muscle

fibers decreases

Nervous system response slows

Exercise and the Elderly

1996 report 30% of the elderly exercise

regularly.

Results in decreased risk for a number of

chronic and debilitating illnesses.

US Department of Health and Human Services

Assess

– Motivation.

– Level of activity that a person is capable of

doing,

– Help him/ her to understand how to change

Health Care for the Elderly

Include

– health promotion,

– disease prevention,

– health maintenance

Anatomical and physiological changes

– cardiovascular

– Genitourinary

– Neurological

– musculoskeletal

respiratory

endocrine

skin