Splenic Artery Thrombosis in a Patient with Prothrombin Mutation

advertisement

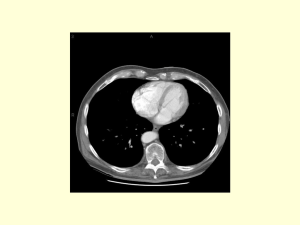

Splenic Artery Thrombosis in a Patient with Prothrombin Gene Mutation Jennifer Teeter, D.O. Mentor: Dr. Kamal D. Tourbaf, M.D. Virchow’s triad • The major theory delineating the pathogenesis of thrombosis – Alterations in blood flow – Vascular endothelial injury – Inherited or acquired hypercoagulable state1 Inherited Thrombophilia • Factor V Leiden mutation • Prothrombin gene mutation2 • • • • Protein C deficiency Protein S deficiency Antithrombin deficiency MTHFR mutation Acquired risk factors • 50% of thrombotic events in patients with inherited thrombophilia are associated with an acquired risk factor – Pregnancy – Surgery – Prolonged bedrest – Malignancy – Trauma – Smoking – Oral contraceptives3 • The majority of thrombosis are venous rather than arterial. • The majority occur within the lower extremities. Our Case • We describe a patient with prothrombin gene mutation and tobacco use causing splenic artery thrombosis and subsequent splenic infarct after abdominal trauma. History • 43-year-old Caucasian male presented to the ER with complaints of nausea and vomiting for 3 days. • In addition, he had left upper abdominal and left flank pain for 1 day. ROS • Left lower chest and left upper abdomen bruised 3 weeks prior to presentation after he bumped into a shelf. • Denies fever, urinary burning or frequency, SOB or changes in bowel habits. • • • • • PMHx: Gout PSHx: none Meds: none Allergies: NKDA Social: +tobacco <1ppd X 15 years, denies alcohol or drug use. • FHx: mother had breast cancer and LE DVT’s Physical Exam • Vitals: 133/89 100 20 100.5 100%RA • 43-year-old caucasian male in moderate distress, A+Ox3 • HEENT: NCAT, EOMI, PERRLA, OMM, clear pharynx • Neck: no bruits, no thyromegaly • Heart: RRR S1S2, no murmurs • Lungs: CTA b/l no w/r/r PE con’t • Abdomen: soft, nondistended, +BS, significant LUQ and left flank tenderness with minimal palpation and with deep inspiration. No rebound or guarding. • Ext: no edema, negative homans • Neuro: CN II-XII grossly intact, muscle strength, reflexes, sensation intact • Rectal: heme occult negative Labs • • • • • • • • • WBC 15.5 HgB 15.7 Hct 44.6 Plt 188 N 77% L 7% M 15% E 2% B0 Na 138 Cl 100 K 3.3 CO2 29 BUN 11 Cr 0.9 gluc 116 amylase 67 lipase 22 Ca 9.3 T. Bili 1.0 D. Bili 0.2 T. Pro 7.4 Alb 4.1 ALT 29 AST 29 alk phos 66 U/A • Negative glucose, ketones, leuk. Esterase, nitrites, protein, bilirubin • + trace blood, few bacteria, 5-10 squamous epithelial cells EKG • Sinus tachycardia CT abdomen and pelvis without contrast • Subtle stranding involving the superior aspect of the body of the pancreas and around the left adrenal gland • Left renal cyst • No evidence of hydronephrosis, renal, ureteral or bladder calculi CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast • Enlarged spleen, 15.1 cm, with patchy areas of enhancement. The majority of the spleen does not appear to enhance, suggestive of ongoing splenic infarction. • The splenic artery also does not enhance, suggestive of thrombosis • Left renal cyst Hospital Course • The patient was followed by a vascular surgeon, a general surgeon and a hematologist. • He was managed conservatively with IV heparin which was bridged to coumadin. • His pain was controlled with analgesic medication. • A cause for the thrombosis was evaluated. Studies • Lower extremity venous dopplers: negative for DVT • Normal lower extremity arterial dopplers • 2D echo: left ventricular EF 50%; poor overall images, normal right ventricular systolic function, mild thickening of aortic valve leaflets. • TEE with bubble study: normal left and right ventricular systolic function. No evidence of cardiac source of embolism. Hypercoagulable Workup • • • • • Protein C 114% (71-146%) Protein S 105% (74-146%) No resistance to activated protein C Factor V Leiden negative Antithrombin III 94% (81.1-125.9%) Con’t • • • • • • C-ANCA <6 u/ml (negative) P-ANCA <6 u/ml (negative) Phospholipids 207 mg/dL (151-264 mg/dL) Thrombin time 20 sec (16-23 sec) No evidence of lupus anticoagulant Cardiolipin antibodies normal Positive Labs • Factor II mutation positive – Genotype: heterozygous • + one copy of MTHFR mutation – The presence of one copy has not been associated with an increased risk for hyperhomocysteinemia or vascular disease. • • • • • CRP 11.300 mg/dL ESR 74 mm/hr (0-15 mm/hr) Fibrinogen 660 mg/dL (250-500 mg/dL) Homocystine 18.3 umol/L (5-15 umol/L) Factor VIII 209% (50-150%) Acute gouty attack • Right second metatarselphalangeal joint during his course of illness. • Uric acid 6.0 9.3 • Treated with colchicine Repeat Labs • Fibrinogen 302 mg/dL (250-500 mg/dL) • Homocystine 14.4 umol/L (5-15 umol/L) • Factor VIII 147% (50-150%) • Therefore, it is felt that the initial elevation of this patient’s fibrinogen, homocystine and Factor VIII were due to an acute phase response secondary to the splenic infarction and gouty attack. • We concluded that this patient’s hypercoagulability is most likely a result of his Factor II mutation. • In addition, the patient’s abdominal trauma and tobacco use may have played an additive role. • We recommended long-term anticoagulation and discontinuation of tobacco use. • Family members, including siblings and children, were advised to be tested for the Factor II mutation. DISCUSSION Splenic Infarction • Acute occlusion of the splenic artery results in infarction of the splenic parenchyma. • Patients present with left upper quadrant pain, fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, pleuritic chest pain and left shoulder pain5. Splenic Infarction • Usually encountered in association with – hematological diseases – Thromboembolic states – Vasculitides: SLE with lupus anticoagulant or antiphospholipid antibodies5 – Sickle cell disease – Wegener’s granulomatosis – Cocaine abuse6 Splenic Artery • Abnormalitites of the splenic artery, particularly stenosis and occlusion, are rare types of acquired disorders of splanchnic circulation. • Etiological factors: – Blunt trauma – liver transplantation surgery or pancreatectomy – torsion of the wandering spleen5,7-8 Splenic Artery Thrombosis • Thrombosis of the abdominal aorta and splenic artery in antiphospholipid syndrome9 • Thromboembolic process of cardiac origin causing stenosis of the splenic artery10 • Secondary to oral contraceptive use11 • Thromboembolic splenic infarction due to atherosclerosis of the thoracic aorta and splenic artery12 Splenic A. Thrombosis Con’t • Spontaneous splenic infarction after sumatriptan use13 • DM with atheromatous arteries and thrombosis of the sclerosed splenic artery14 • Asymptomatic splenic artery occlusion in a child discovered with doppler U/S15 • To our knowledge, a case on splenic artery thrombosis in a patient with prothrombin mutation has never been reported. Thrombophilia • The blood has an increased tendancy to clot • Risk Factors: – – – – – – – – – – – Inherited risk factor Obesity Cancer Inflammatory bowel disease Antiphospholipid antibodies Recent surgery Trauma Prolonged immobility Pregnancy Oral contraceptive use Hormone replacement therapy16 Thrombophilia Con’t • Thrombophilia is a prominent risk factor for venous thromboembolism. • The role of thrombophilia in determining the risk of arterial thrombotic events is less well defined. Prothrombin • A protein in the blood that is required to form fibrin which combines with platelets to form blood clots. • A mutation in the prothrombin gene, also called prothrombin variant, prothrombin G20210A, or factor II mutation, has been associated with a 30% higher plasma prothrombin level and therefore an increased tendency for thrombosis18. Prothrombin Con’t • Heterozygous or homozygous • Heterozygous mutations are found in about 2% of the US Caucasian population. • The homozygous form is uncommon, 1/10,000. • Heterozygous prothrombin mutation increases the risk of developing a DVT by 2-3 times16. • It plays a role in cerebrovascular ischemic events in those less than 60 years of age. There is conflicting results when evaluating the role of prothrombin gene mutation in acute myocardial infarction19-21. • Many people with this mutation will never develop a blood clot • Often, people will have additional risk factors for clot formation. • If a patient has the prothrombin mutation but has not developed a blood clot, they should be counseled about reducing or eliminating other factors that add to their risk of developing a blood clot in the future16. • Several studies have shown a correlation between tobacco use and an increased risk for venous thromboembolism22-24. • A large population-based study investigated the VTE risk following a minor injury and concluded that a minor injury occurring in the preceding 3 to 4 weeks was associated with a 3- to 5-fold increase in DVT risk26. • Risk factor modification is also important for preventing arterial disease. • It is likely that, in our patient, his tobacco use and/or abdominal blunt trauma contributed to his development of thrombosis. Acute gouty attack • We were unable to find any evidence that gout is an independent risk factor for increased coagulabilty. • Nevertheless, gout is associated with a number of risk factors for cardiovascular disease including hypertension, obesity, a high alcohol intake and hyperlipidemia. • In view of the already raised thrombotic risk profile in gout patients as a group, one study showed that the hyperfibrinogenemia was only present during the acute attack of gout, presumably as an acute phase response. • They concluded that it is unlikely that the hyperfibrinogenemia noted during acute attacks of gout contributed significantly to the chronically raised cardiovascular risk profile of long-term gout patients27. Acute Phase Response • Raised fibrinogen, homocystine and factor VIII levels have been recognized as risk factors for thrombosis. • Although these levels were initially elevated in our patient, they did return to normal limits after the splenic infarction and the resolution of his acute gouty attack. • We concluded that these elevations were due to the acute phase response and most likely did not play a significant role in the risk of thrombosis in this patient CONCLUSION • Thrombosis occurs as a result of disruption of blood flow, vascular endothelial damage and/or a hypercoagulable state. • A common cause of inherited thrombophilia is prothrombin gene mutation. • Thrombophilia is a prominent risk factor for venous thromboembolism; however, the risk for arterial events is less well defined. • There are many reported causes for splenic artery thrombosis and splenic infarction. • However, we believe we are the first to report a case of splenic artery thrombosis and subsequent splenic infarction in a patient with prothrombin gene mutation and tobacco use who sustained abdominal trauma. • Although our patient had elevated fibrinogen, homocystine and factor VIII levels, we determined that these were acute phase reactants. References 1. B.C. Dickson. Venous thrombosis: on the history of Virchow’s triad. Univ. Toronto Med J. 2004; 81:166. 2. B. Dahlback. Advances in understanding pathogenic mechanisms of thrombophilic disorders. Blood 2008; 112:19. 3. R.M. Bertina. Genetic approach to thrombophilia. Throb Haemost 2001; 86:92. 4. Quest diagnostics 5. M. Nores, E.H. Phillips, L. Morganstern, J.R. Hiatt. The clinical spectrum of splenic infarction. Am Surg, 1998; 64:182-188. 6. J.C. Chen, Y.N Hsiang, D.C. Morris, W.B. Benny. Cocaine-induced multiple vascular occlusions: A case report. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 1996;23(4):719723. 7. C. Goerg, W.B. Scwerk. Splenic infarction: sonographic patterns, diagnosis, follow0up and complications. Radiology, 1990; 174:603-607. 8. D.C. Desai, A. Hebra, A.M. Davidoff. Wandering spleen: a challenging diagnosis. South Med J, 1997; 90:439-444. 9. G. Brancatelli, M. Galia, S. Cusma, M. Molino. Thrombosis of the abdominal aorta and splenic artery in antiphospholipid syndrome. Description of a case studied with computerized tomography. Radiologia Medica, 2000; 99(1-2):101-103. 10. J.H. O’Keefe, D.R. Holmes, H.V. Schaff. Thromboembolic splenic infarction. Mayo Clinic Proc, 1986; 61:967-972. 11. E. Weinstein, L. Silverman. Splenic artery thrombosis secondary to oral contraceptive medication: a case report. Military Medicine, 1982 Jul; 147(7):589-90. 12. F. Frippiat, J. Donckier, P. Vandenbossche, M. Stoffel, B. Boland, M. Lambert. Splenic infarction: report of three cases of atherosclerotic embolization originating in the aorta and retrospective studies of 64 cases. Acta Clinica Belgica, 1996; 51(6):395-402. 13. A. Arora, S. Arora. Spontaneous splenic infarction associated with sumatriptan use. J. Headache Pain, 2006; 7:214-216. 14. J.A.M. Cameron. A case of splenic artery thrombosis. Canad. M. A. J., 1949; 61:624. 15. H. Ozcan, B. Yagmurlu, M. Koral. Asymptomatic splenic artery occlusion in a child: incidental detection with Doppler ultrasonography. Diagn Interv Radiol, 2006; 12:68-69. 16. E. Varga, S. Moll. Prothrombin 20210 Mutation. Circulation, 2004;110:e15-e18. 17. S.M. Boekholdt, M.H. Kramer. Arterial thrombosis and the role of thrombophilia. Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis, 2007; 33(6):588-596. 18. M. Margaglione, B. Brancaccio, N. Giuliani, G. D’Andrea et al. Increased risk for venous thrombosis in carries of the prothrombin G A20210 gene variant. Ann Intern Med, 1998; 129 (2):89-93. 19. A.M. Smiles, N. S. Jenny, Z. Tang, et al. no association of plasma prothrombin concentration or the G20210A mutation with incident cardiovascular disease: results from the cardiovascular heath study. Thromb Haemost 2002; 87:614. 20. W. Lalouschek, M. Schillinger, K. Hsieh, et al. Matched case-control study on factor V Leiden and the prothrombin G20210A mutation in patients with ischemic stroke/transient ischemic attack up to the age of 60 years. Stroke 2005; 36:1405. 21. J. W. Eikelbloom, R.I. Baker, R. Parsons, et al. No association between the 20210 G/A prothrombin gene mutation and premature coronary artery disease. Thromb Haemost 1998; 80:878. 22. S.Z. Goldhaber, F. Grodstein, M.J. Stampfer, et al. A prospective study of risk factors for pulmonary embolism in women. JAMA, 1997; 277:642. 23. R. D. Farmer, R.A Lawrenson, J.C. Todd, et al. A comparison of the risks of venous thromboembolic disease in association with different combined oral contraceptives. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2000; 49:580. 24. E. R. Pomp, F.R. Rosendaal, C.J. Doggen. Smoking increases the risk of venous thrombosis and acts synergistically with oral contraceptive use. Am J Hematol, 2008; 83:97. 25. J.T. Owings, R. Gosselin. Acquired antithrombin deficiency following severe traumatic injury: rationale for study of antithrombin supplementation. Semin Thromb Hemost 1997; 23 Suppl 1:17. 26. K.J. van Stralen, F.R. Rosendaal, C.J. Doggen. Minor injuries as a risk factor for venous thrombosis. Arch Intern Med, 2008; 168:21. 27. D. J. C. Ramsey, S. Cotton, E. S. Lawrence, M. J. Semple, P. F. Worth, et al. Clotting factors in patients with acute and chronic gout. J. Med. Sci 2005; 5(1):4751.