statusepilepticus

advertisement

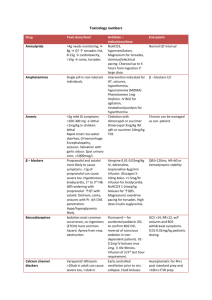

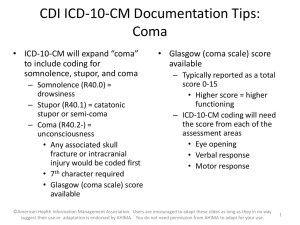

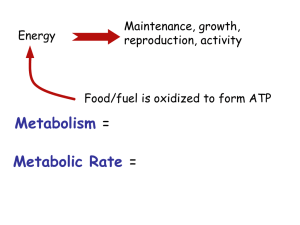

Status Epilepticus PICU Resident Lecture Series Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital (Updated: April 2011) Objectives • What are common causes of SE • Learn the physiologic sequela of SE – (Why do these patients need to be in the PICU?) • Learn what tests/labs are needed acutely • Acute management of SE – Including procedures, medications, and “pentobarb” comas Definitions • No absolute definition of Status Epilepticus (EP) • Generally accepted definition is – Greater than 30 minutes OR – Frequent seizures without returning to baseline • Treatment if seizure lasts >5 minutes – High risk of lasting >30 minutes – Delayed treatment can lead to permanent sequela Common etiologies Common drugs related to seizures • • • • • • • Penicillins • Isoniazid • Metronidazole • Antihistamines • Narcotics Ketamine Halothane/Enflurane Tricyclic antidepressants Antipsychotics Phencyclidine Cocaine Physiologic Consequences of SE • • • • • • Phases of SE Respiratory Effects Hyperpyrexia Metabolic derangements Laboratory changes Summary Phases of SE • Hyperdynamic Phase – Increased cerebral metabolic demand – Massive catecholamine/autonomic discharge – Increased CBF, HTN, tachycardia • Exhaustive Phase (with persistent SE) – Catecholamine depletion – Hypotension, decreased CBF – Can lead to neuronal damage (ongoing metabolic demand with tissue hypoxia) Respiratory Effects • Hypoxia and Hypercarbia are common – Chest wall rigidity (muscle spasms, oral secretions) – Hypermetabolic state with increased 02 demand and increased C02 production – Neurogenic pulmonary edema is rare complication • Marked increased in pulmonary vascular pressure is presumed etiology Hyperpyrexia • Can lead to seizures or be a result of SE • Exacerbates mismatch of cerebral metabolic demand and substrate delivery • Therefore fevers should be treated aggressively – Antipyretics/cooling Metabolic derangements • Acidosis – Lactic acidosis due to poor tissues oxygenation with inc energy expenditure – Respiratory acidosis may also develop • Glucose – Initial hyperglycemia from catecholamine surge followed by hypoglycemia – Can be detrimental to the brain, and can further worsen lactic acidosis Metabolic derangements (cont’d) • Rhabdomyolysis – Protracted tonic-clonic activity can have extensive muscle breakbdown – Leads to hyperkalemia, myoglobinuria • Leukocytosis – Stress response causes demarginalization of SBCs – In 15% of children, this leukocytosis can be seen in the CSF Summary of complications Treatment • • • • • ABCs Venous access Labs Other diagnostic Meds ABCs • Avoid hypoxia by providing oxygen (facemask or NC) • Oral airway can be helpful (but difficult to place) • Nasal trumpet is good alternative • Optimize position, jaw thrust • If poor respiratory effort, begin bag-mask ventilation and consider intubation Intubation • Some indications: – Difficult to maintain airway – Unable to manage oral secretions – Ineffective respiration – Hypoxia – Hypercarbia – CNS pathology, unequal pupils – SE >30 minutes despite appropriate treatments • REMEMBER: paralytics DO NOT control CNS epileptiform discharges Venous access • Obtain IV/IO access – Can give IM or Rectal meds but venous access is necessary • Blood pressure management – Hypertension likely to resolve with sz control – Some cases need tx (like inc BP with renal failure) – Start volume resuscitation if hypotensive with bolus of NS (20ml/kg) • Labs required in ALL pts with SE: – CBC, Chem panel (with LFTs, glucose, ca, mg) • Hyponatremia and hypocalcemia are readily treatable – Stat beddside glucose (*especially in neonates and infants) – Ammonia – Anticonvulsant levels – Tox screen • LP: defer in pts with signs of increased ICP or if unstable (but do not delay therapy i.e. abx) Other diagnostics • CT scan – Focal seizures or deficits; History of trauma – Non-contrast: mass lesions, hemorrhage, hydrocephalus – Contrast: meningitis, abscess, encephalitis • EEG- indicated in ALL pts with SE – Standard: one time study in SE that has resolved – Continuous: difficult to control SE, burst suppresion, subclinical seizures – Video: can be used in conjunction for seizures that are difficult to characterize Medications • Initiate antiepileptic therapy early • With delayed treatment, pt will also have delayed response to treatment – Thus requiring higher doses • Combine rapid acting to control with long acting to prevent recurrence Rapid Acting Anticonvulsants Long Acting Anticonvulsants Persistent SE • “Pentobarb” coma – CNS electrical quiescence by continuous infusion – Pentobarbital: 1-3mg/kg/hr after bolus (10mg/kg) – Midazolam: 1-10mcg/kg/min after bolus (0.15mg/kg) – Propofol 20-70 mcg/kg/min • Normal physiologic activity also suppressed – Intubation necessary “Pentobarb” coma (cont’d) • Central line placement – For delivery of continuous infusion – May cause hypotension so pt may require rapid fluid bolus or inotropes • Treat hypotension aggressively in these pts • Continuous EEG – “Burst suppression” is the specific electric pattern noted on EEG once in a successful coma. Electrical activity is only noted once per screen (15-20sec) “Pentobarb” coma (cont’d) • Pt must be started on a long acting anticonvulsant – Check for therapeutic levels • Burst suppression for 24-48 hrs – Coma gradually lifted while monitoring for seizure activity Non-convulsive SE • Up to 20% of children with SE have nonconvulsive SE after tonic-clonic activity • If no response to painful stimulation within 20-30 min of tonic-clonic activity • Urgent EEG • Must maintain High Index of Suspicion • Often difficult to assess (i.e. previous medications, post-ictal state) • Neurology consult is imperative