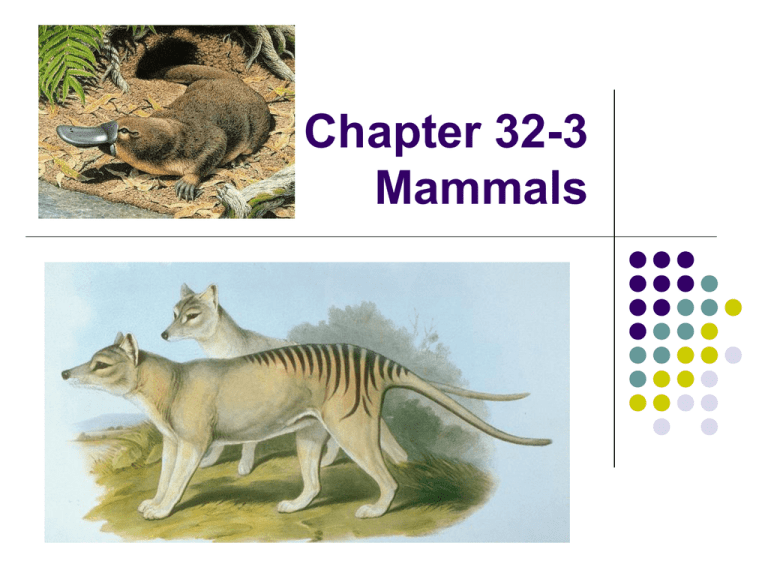

Chapter 32-3

Mammals

32-3 Primates and Humans

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

32-3 Primates and Human

Origins

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Mammals: Primates

What Is a Primate?

What

Is a Primate?

In

general, primates have binocular

vision, a well-developed cerebrum,

relatively long fingers and toes, and arms

that can rotate around their shoulder joints.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

What Is a Primate?

Fingers,

Toes, and Shoulders

Flexible digits enable primates to run along tree

limbs and swing from branch to branch with

ease.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

What Is a Primate?

Primates’

arms are well adapted to climbing

because they can rotate in broad circles around

a strong shoulder joint.

In most primates, the thumb and big toe can

move against the other digits. This

characteristic allows primates to hold objects in

their hands or feet.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

What Is a Primate?

Well-Developed

Cerebrum

The large cerebrum of primates enables them

to display more complex behaviors than many

other mammals.

Many species have social behaviors that

include adoption of orphans and even warfare

between rival primate troops.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

What Is a Primate?

Binocular

Vision

Many primates have a flat face, so both eyes

face forward with overlapping fields of view. This

facial structure allows for binocular vision.

Binocular vision is the ability to merge visual

images from both eyes, providing depth

perception and a three-dimensional view of the

world.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Evolution of Primates

Evolution

of Primates

The

two main groups of primates are

prosimians and anthropoids.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Evolution of Primates

Hominoids

Lorises and

Bush Babies

Lemurs

New

Old World

World

Monkeys Orangutans Chimpanzees

Monkeys

Gibbons

Gorillas

Humans

Tarsiers

Prosimians

Primate ancestor

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Anthropoids

Evolution of Primates

Prosimians

Most

prosimians alive today are small,

nocturnal primates with large eyes that are

adapted to seeing in the dark.

Living prosimians include bush babies, lemurs,

lorises, and tarsiers.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Order Primates

Prosimian: A Lemur

Monkeys are Anthropoids

Order Primates

Evolution of Primates

Lorises and

Bush Babies Lemurs Tarsiers

Prosimians

Primate Ancestor

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Evolution of Primates

Anthropoids

Humans,

apes, and most monkeys belong to a

group called anthropoids, which means

humanlike primates.

This group split early in its evolutionary history

into two major branches.

These branches separated as drifting

continents moved apart.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Evolution of Primates

New World Old World

Orangutans

Gorillas Chimpanzees Humans

monkeys

monkeys Gibbons

Anthropoids

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Evolution of Primates

One

branch of anthropoids is the New World

monkeys. New World monkeys:

live almost entirely in trees.

have long, flexible arms to swing from

branches.

have a prehensile tail, which is a tail that can

coil around a branch to serve as a “fifth hand.”

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Evolution of Primates

The

other group of anthropoids includes Old

World monkeys and great apes.

Old World monkeys live in trees but lack

prehensile tails.

Great apes, also called hominoids, include

gibbons, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees,

and humans.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Hominid

Evolution

Between 6 and 7 million years ago, the hominoid

line gave rise to hominids. The hominid family

includes modern humans.

As hominids evolved, they began to walk upright

and developed thumbs adapted for grasping.

They also developed large brains.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Modern human

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Modern human

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

The

skull, neck, spinal column, hipbones, and

leg bones of early hominid species changed

shape in ways that enabled later hominid

species to walk upright.

Evolution of this bipedal, or two-foot,

locomotion freed both hands to use tools.

Hominids evolved an opposable thumb that

enabled grasping objects and using tools.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Hominids

displayed a remarkable increase in

brain size, especially in an expanded

cerebrum—the “thinking” area of the brain.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Early

Hominids

At present, the hominid fossil record includes

these genera:

Ardipithecus

Australopithecus

Paranthropus

Kenyanthropus

Homo

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

There

are as many as 20 separate hominid

species.

This diverse group of hominid fossils covers

roughly 6 million years.

All are relatives of modern humans, but not all

are human ancestors.

Questions remain about how fossil hominids

are related to one another and to humans.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Australopithecus

An

early hominid species, Australopithecus, lived

from about 4 million to 1 million years ago.

The structure of Australopithecus teeth suggests

a diet rich in fruit.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

The

best known species is Australopithecus

afarensis—based on a female skeleton

named Lucy, who was 1 meter tall.

Members of the Australopithecus species

were bipedal and spent some time in trees.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Paranthropus

The

Paranthropus species had huge, grinding

back teeth.

Their diets probably included coarse and fibrous

plant foods.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Recent

Hominid Discoveries

In 2001, a team had discovered a skull in

Kenya.

Its ear resembled a chimpanzee’s.

Its brain was small.

Its facial features resembled those of Homo

fossils.

It was put in a new genus, Kenyanthropus,

which lived at the same time as A.

afarensis.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Kenyanthropus platyops

Homo erectus

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

In

2002, paleontologists working in the desert in

north-central Africa discovered another skull.

Called Sahelanthropus, it is nearly 7 million

years old.

If it is a hominid, it would be a million years

older than any hominid previously known.

It had a brain like a modern chimp and a flat

face like a human.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Sahelanthropus tchadensis

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Rethinking Early Hominid Evolution

Researchers once thought that human

evolution took place in steps, in which hominid

species became gradually more humanlike.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Hominid

evolution did not proceed by the

simple, straight-line transformation of one

species into another.

Rather, a series of complex adaptive

radiations produced a large number of

species whose relationships are difficult to

determine.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

Millions of years ago

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Hominid Evolution

The

hominid fossil record dates back 7 million

years, close to the time that DNA studies

suggest for the split between hominids and the

ancestors of modern chimpanzees.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Known or Suspect Hominids

Simplified Tree

Australopithicus afarensis

Homo habilis

Homo erectus

H. erectus lived from approximately 1.8

to 0.5 million years ago and perhaps

even longer

H. erectus was the most successful of the

the genus Homo lineages in terms of

time on Earth

H. erectus spread her kind throughout

the old world

H. erectus

Homo erectus

Pan

Homo

erectus

H. sapiens

The Road to Modern Humans

The

Road to Modern Humans

Paleontologists still do not completely

understand the history and relationships of

species within our own genus.

Other species in the genus Homo existed

before Homo sapiens.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

The Road to Modern Humans

The

Genus Homo

The first fossils in the genus Homo are about

2.5 million years old.

These fossils were found with tools, so

researchers called the species Homo habilis,

which means “handy man.”

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

The Road to Modern Humans

2

million years ago, a species called Homo

ergaster appeared. It had a bigger brain and

downward-facing nostrils that resembled those of

modern humans.

At some point, either H. ergaster or a related

species named Homo erectus began migrating

out of Africa through the Middle East.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

The Road to Modern Humans

Out

of Africa—But Who and When?

Evidence suggests that hominids left Africa in

several waves, as shown in the following

diagram.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

The Road to Modern Humans

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

The Road to Modern Humans

It

is not certain where and when Homo

sapiens arose.

One hypothesis, the multi-regional model,

suggests that modern humans evolved

independently in several parts of the world from

widely separated populations of H. erectus.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

The Road to Modern Humans

Another

hypothesis, the out-of-Africa model,

proposes that modern humans evolved in Africa

between 200,000–150,000 years ago, migrated

out to colonize the world, and replaced the

descendants of earlier hominid species.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Modern Homo sapiens

Modern

Homo sapiens

The

story of modern humans over the past 500,000 years

involves two main groups.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Modern Homo sapiens

The

earliest of these species is called Homo

neanderthalensis.

Neanderthals lived in Europe and Asia

200,000–30,000 years ago.

They made stone tools and lived in organized

social groups.

The other group is Homo sapiens—people

whose skeletons look like those of modern

humans.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Modern Homo sapiens

50,000–40,000

years ago some populations of

H. sapiens seem to have changed their way of

life:

They made more sophisticated stone blades and

elaborately worked tools from bones and antlers.

They produced cave paintings.

They buried their dead with elaborate rituals.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

Modern Homo sapiens

About

40,000 years ago, a group known as

Cro-Magnons appeared in Europe.

By 30,000 years ago, Neanderthals had

disappeared from Europe and the Middle East.

Since that time, our species has been Earth’s

only hominid.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

32-3 Quiz

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

32-3

The ability to merge visual images from both

eyes is called

monocular vision.

binocular vision.

overlapping vision.

color vision.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

32-3

a.

b.

c.

d.

Which of the following is true about hominid

evolution?

The development of a large brain happened

before bipedal locomotion.

There is a straight line of descent from the

earliest hominid species to Homo sapiens.

The genus Homo appeared before the genus

Australopithecus.

Hominid evolution took place as a series of

adaptive radiations that produced a large

number of species.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

32-3

The evolution of bipedal locomotion was

important because it

increased brain size.

made it easier to see.

freed both hands to use tools.

allowed easier escape from predators.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

32-3

The multi-regional model hypothesizes that

a. Homo sapiens evolved independently in

several parts of the world.

b. Modern humans evolved in Africa, then

migrated to various parts of the world.

c. Neanderthals produced cave drawings.

d. Homo habilis descended from Homo erectus.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

32-3

The oldest known Homo sapiens skeletons are

about

6,000 years old.

100,000 years old.

3 million years old.

30 million years old.

Copyright Pearson Prentice Hall

END OF SECTION