Late Industrialization

Diffusion of Development: The Late-

Industrializing Model and Greater

East Asia

Alice Amsden

Amsden, Alice H. (1991), “Diffusion of Development: The Late-Industrializing Model and Greater East Asia,” American Economic Review 81 (2), 282-286.

“Late Industrialization”

• Movement from an agrarian base. (note: does not include Hong

Kong and Singapore)

• From 1960-1988 annual economic growth in East Asia was approx.

10.6% vs 6.3% for all developing nations.

• Why?

• Export Growth?

– Between 1973-86, the Philippines nearly twice doubled their manufactured exports to value added exports ratio while economically stagnant.

• Equity?

– Rapid growth in countries with high income inequality. (ie: Brazil,

Indonesia and Singapore)

• Conclusion:

– Need a model rather than individual variables to explain EA growth.

• Market vs Institutional

Industrialization Through Learning

• Late Industrializing Countries have the challenge of growing without development of new technology.

– “learning” in order to compete

• Market Model: follow competitive advantage. “Get prices right.”

– Low wages labor intensive manufacturing

– Japanese textile growth over Britain due to superior facilities rather than wage.

• Korea and Taiwan can’t compete. Required intervention.

• Institutional Model: subsidies used to “get prices wrong.”

– Stimulate investment and trade.

Subsidy Allocation

• Goal: Increase efficiency so that the “wrong prices are right.”

• Subsidies in EA awarded in exchange for meeting performance standards rather than just a giveaway like in other developing countries. (Reduces rent seeking)

• Disciplined subsidies faster growth.

Import Substitution to Exports

• Subsidies early on encouraged import substitution.

• “Standby incentives” for exporters ensured that development would reach globally competitive levels.

– Achieved through low wage gap, educated labor, bonuses based on performance, and adoption of “best practice” on the shop floor.

• Cycle: Import Substitution Phase: 1. Gov’t controlled 2. Export Growth: Market led 3.

Neo-import substitution phase: Gov’t led.

Summary

• Late industrializers struggle to compete on low-wage alone.

• Gov’t intervention/industrial policy a

“necessary evil.”

• Focused subsidies lead to faster growth.

• Allow market forces to take over.

The East Asian Miracle: Four

Lessons for Development Policy

John Page

Page, John. (1994), “The East Asian Miracle: Four Lessons for Development Policy,”

NBER Macroeconomics Annual 9, 219-269.

Fundamentalists vs Mystics

• Fundamentalists:

– factor accumulation,

– getting basics right,

– macro stability,

– investments in people,

– few market failures.

• Mystics:

– “catching up” technologically, (TFP growth)

– market consistently fails to guide investment to high growth industries,

– “get prices wrong,”

– flexible gov’t policies.

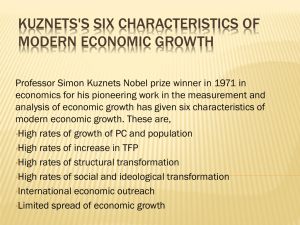

TFP Analysis

• TFP in developing nations is a combination of “catching up” (or falling behind) and efficiency of factor allocation.

• TFP findings not conclusive.

• Fundamentalist:

– “Between 60% and 120% of EA output growth derived from accumulation of physical and human capital and labor force growth.”

• Mystic:

– EA countries are some of the few developing nations that appear to be “catching up” or growing similarly to international best practice.

Success of Export Push

• Import substitution phase shorter than in other economies.

• Japan, Korea and Taiwan: incentives between import substitution and exports neutral on average.

– Not neutral among firms, certain industries pushed.

• EA has an increasingly large share of international exports.

– Manufactured exports contributing most of this growth.

• Manufactured export performance strongly correlated with increased TFP growth.

– Possibly due to “catchup” to best practice.

(In)Significance of Industrial Policy

• “Gov’t efforts to alter industrial structure to promote productivity based growth.”

• Sectoral growth rates of TFP for Japan, Korea and

Taiwan are high by international standards.

– However, growth in promoted sectors not higher than other domestic sectors. (Excluding Japan)

• Between 1966-85, Korea promoted iron, steel, and chemicals which all experienced modest TFP growth. While textiles, a non-promoted industry, had very high TFP growth.

• Industrial policy ineffective at choosing winners?

Conclusion

• While both seem to agree that export promotion played a large role in EA development, Amsden puts a larger emphasis on the importance of the import substitution phase of growth, attributing

“catching up” to this phase rather than the export phase as done by

Page.

• Amsden also strongly advocates the effectiveness of industrial policy in EA, while Page marginalizes it.

• Though Page uses a much larger quantity of statistics in his analysis, much of the EA data (particularly in the TFP analysis) is guesswork.

Additionally, Page asserts that Korea did not promote it’s textile industry through industrial policy, and that is not entirely accurate.

• As such, I feel that Amsden provides a more compelling argument that Industrial Policy did in fact play an important role in EA’s late industrialization.