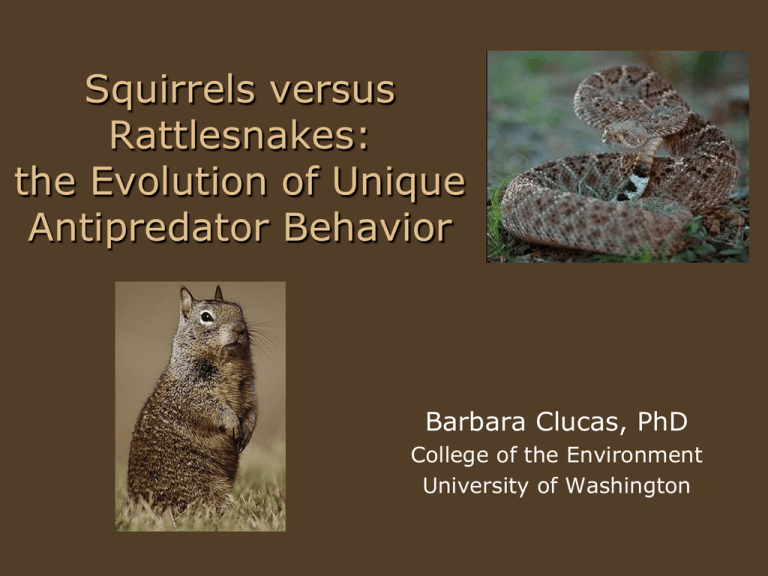

Squirrels versus

Rattlesnakes:

the Evolution of Unique

Antipredator Behavior

Barbara Clucas, PhD

College of the Environment

University of Washington

Animal Behavior

• The study of how animals

use behavior to survive

and reproduce

• How and why

behavior evolves

• Social, reproductive,

movement, antipredator

Animal Behavior

• The study of how animals

use behavior to survive

and reproduce

• How and why

behavior evolves

• Social, reproductive,

movement, antipredator

Antipredator Behavior

• Reduce the risk of

predation

• Most animals are prey

• Evolution of a vast

array of antipredator

behavior

Antipredator Behavior

Ground Squirrels

(Spermophilus)

• Diverse genus of

species

• Worldwide

distribution (except

Australia and Antarctica)

• Live in burrows in

the ground

• Species vary in

habitats and sociality

Ground squirrel predators

Ground squirrel predators

Rattlesnakes

• Warning rattle

• Venomous

• Skilled rodent predators

– Lethal venom

– Acute sense of sight and

smell

– Pit organs can sense

temperature changes

(Crotalus)

rattle

Ground squirrel defenses

• Venom resistant

• Harass, attack

rattlesnakes

• Tail-flagging

– visual and infrared

signal

Rattlesnakes are still predators…

• Ground squirrel pups

– Not large enough to be

venom resistant

– Anti-snake behavior not

fully developed

– Depend on adults for

protection (especially

their mothers)

Recent discovery

• Another unique snake-related

behavior found in certain species

of ground squirrels

• “Snake scent application”

Snake Scent Application

Snake Scent Application (SSA)

1. Why are squirrels applying

rattlesnake scent?

• Test 3 functional hypotheses

2. Evolutionary history

• Phylogenetic comparative methods

Functional hypotheses of

SSA

1. Antipredator

2. Social

3. Ectoparasitic defense

1. Antipredator

• SSA disguises

squirrel odor

– Rattlesnakes

may bypass

burrows with

snake-scented

squirrels

2. Social

• Conspecific

deterrence

• SSA deters rivals

– Snake-scented

squirrels win more

aggressive

encounters

3. Ectoparasite defense

• SSA reduces

fleas

– Flea host-finding

behavior affected

by snake scent

Testing hypotheses of function

• Study 1: Time spent applying

snake scent

– Which squirrels apply more?

• Study 2: Series of experiments

directly testing targets

– What are the effects of snake scent?

Study 1:

Which squirrels SSA more?

Study species

• California ground squirrel,

(S. beecheyi)

– Winters, California

• Rock squirrel,

(S. variegatus)

– Caballo, New Mexico

Study 1:

Which squirrels SSA more?

• Trapped and marked

squirrels

• Recorded:

– sex

– age

– flea load

Quantifying application behavior

• Staked out shed

rattlesnake skins

• Filmed individual

squirrels

• Recorded duration of

SSA

Predictions

1. Antipredator

• adult females & pups > adult males

2. Conspecific deterrence

• adult males > adult females & pups

3. Ectoparasite defense

• time spent related to flea load

• pups > adults

Adult females & pups > adult males

*P < 0.005; Error bars = SE

Clucas et al. 2008, Anim Behav

SSA not related to flea load

None

Low

Med

Spearman rank correlation: rs: -0.033, N=45, P=0.829

High

Clucas et al. 2008, Anim Behav

Study 1: Antipredator hypothesis supported

• Pups most susceptible to predation,

adult females share burrows with and

protect their pups

• No support for alternative hypotheses

– squirrels with more fleas do not apply more

– most aggressive squirrels (adult males) do

not SSA the most

Study 2: What are the effects of snake scent?

• Experiment 1: Rattlesnake foraging

behavior

• Experiment 2: Squirrel behavior

before and after applying

• Experiment 3: Flea host choice

Experiment 1

Rattlesnake Foraging Behavior

• 3 scent-type trials

1. Ground squirrel

2. Ground squirrel

+Rattlesnake

3. Rattlesnake

• Water control

C. oreganus

oreganus

N=8

Experiment 1

Rattlesnake Foraging Behavior

• Behavior scored

– Time spent over

– Tongue-flicking

C. oreganus

oreganus

N=8

Experiment 1

Spent more time over ‘squirrel’

Tim e Ove r (s e co n d s ) + / - SE

250

200

150

100

50

0

Sce n t

Wa te r

- 50

N=

8

8

8

Sq u irr el

8

Rattles n a ke

8

8

Sq u irr e l+ Ra ttle s n ak e

Scen t Typ e

Repeated measures GLM: F2,14=4.667, P = 0.028; planned

comparisons: all P<0.05

Clucas et al. 2008, PRSL

Experiment 1

Tongue flicked more over ‘squirrel’

100

To n g u e Flic ks + / - SE

80

60

40

20

0

Sce nt

-20

N=

Wa te r

8

8

Squirrel

8

8

Rat tlesnake

8

8

Squirrel+ Rat t les nake

Sce n t Typ e

Repeated measures GLM: F2,14=4.478, P = 0.031;

planned comparisons: Sq>R P=0.03, Sq>S+R P=0.07

Clucas et al. 2008, PRSL

Experiment 2

Before and After SSA behavior

SCENTED

Pre-trial

SSA trial

24-48 hours

Post-trial

24-48 hours

CONTROLS

Pre-trial

No SSA trial

24-48 hours

24-48 hours

Post-trial

Experiment 2

Before and After SSA behavior

• Recorded:

– Social interactions

(aggressive or tolerant)

Experiment 2

Social Interactions

SCENTED

* No differences between before

and after

CONTROLS

* No differences between before

and after

Repeated Measures GLM; P>0.05

Clucas et al. 2008, PRSL

Experiment 3

Flea host choice

• Juvenile ground

squirrels as

hosts

• Fleas

– Removed from

ground squirrels

Control

Squirrel

Flea

starting

point

SSA

Squirrel

Experiment 3

Flea host choice

?

• Flea behavior

recorded

?

– Choice

– Latency to move

– Choice latency

Control

Squirrel

Flea

starting

point

SSA

Squirrel

Experiment 3

Fleas not affected by snake scent

• No significant difference in choice

(21=0.455, N=56, P=0.500)

=

=

• Latencies did not differ by choice

– Latency to move: t53=0.661,

P=0.512

– Choice latency: t53=-0.030,

P=0.976

Clucas et al. 2008, PRSL

Study 2: Antipredator hypothesis supported

•

Rattlesnake foraging behavior affected

by snake scent

•

No support for alternative hypotheses

– Neither conspecific behavior nor flea

behavior affected by snake scent

Function of Applying

Snake Scent

• All evidence supports

an antipredator function

• Olfactory camouflage

– Snakes did not avoid

rattlesnake scent, rather

showed low foraging

behavior

Evolutionary history

• Explore the origins of applying

snake scent

– When did it evolve?

– What caused it to evolve?

Studying evolutionary history

• Phylogenetic

comparative

methods

• Phylogenetic tree

Evolutionary history

Common

Ancestor

?

Evolutionary history

?

Ground

squirrel

phylogeny

• Molecular

(cytochrome b)

• Divergence

times

– Time (in

million of

years) when

species

diverged

Comparative study

• Tested multiple ground squirrel

and chipmunk species with

rattlesnake scent

• Recorded presence/absence of

application behavior

When did scent application originate?

• Ancestor state reconstruction

– estimate whether squirrel ancestors

possessed the scent application trait

using maximum likelihood analysis

Ancestral State

Reconstruction

• Common

ancestor likely

had behavior

• Behavior lost

several times

What caused SSA to evolve?

• Is rattlesnake

presence related to

scent application?

– Test with correlated

trait evolution

analysis

SSA Correlated with rattlesnake presence

Correlated Trait Evolution

Snake Scent Application (SSA)

Gain

SSA

Retain

SSA

Lose

SSA

No

SSA

Transition

qij

No Pred, No SSA to No Pred, SSA

Pred, No SSA to Pred, SSA

No Pred, SSA to Pred, SSA

Pred, SSA to No Pred, SSA

No Pred, SSA to No Pred, No SSA

Pred, SSA to Pred, No SSA

Pred, No SSA to No Pred, No SSA

No Pred, No SSA to Pred, No SSA

q12

q34

q24

q42

q21

q43

q31

q13

Inde pe n de nt De pe nde nt

model

model

0.06681

0.07035

5.46777

12.26164

0.000002

0.04732

1.36796

0.06255

0.04732

14.32849

0.06681

0.0000003

L(I)

-11.5970

L(D)

-5.1190

L(R)

12.95

p<0.02

However…

• Current predator presence

• What about historical

co-occurrence?

Historical predator presence

• Fossil records

– established

squirrel and

rattlesnake

co-occurrence

in the past

Historical predator presence

• First squirrel fossil about 30 mya

• First squirrel-rattlesnake cooccurrence about 15 mya

Squirrel and

rattlesnake

ancestors

• Behavior

evolved

before cooccurrence

Original sources of selection

• Snake scent application

evolved at least 28 mya

– Rattlesnake ancestor not

present until 15 mya

• Original source of selection

may have been older snake

species (e.g., Boavus spp.)

More Recent Past: 10-400

thousand years ago

• Presently existing squirrel species

– Species that do not SSA did not historically

co-occur with rattlesnakes

– Species that do SSA did historically cooccur with rattlesnakes

Past and Present

• Typically species had both historic and

present co-occurrence with rattlesnakes

• However, there were several

exceptions…

Interesting exceptions…

• California ground

squirrels in Davis, CA

– Historically had

rattlesnakes

– Ended about 9000 years

ago

• Do not apply snake

scent

• Behavior rapidly lost

Interesting exceptions…

• Belding’s ground squirrels

in MWR, OR

– Did not have rattlesnakes

historically

– Currently do co-occur

• Do not apply snake scent

• Behavior not regainable?

Final Conclusions

• Squirrels apply predator scents to

reduce predation risk

• Predator scent application is an

evolutionarily ancient trait in squirrels

• Original source of selection unknown

• Recent past, behavior maintained by

rattlesnake presence, dependent on

historic co-occurrence

Antipredator behavior:

applications for conservation

• Captive breeding programs

– Will individuals in captivity maintain

antipredator behavior?

• Reintroductions of predators

– Will individuals from predator-naïve

populations be able to defend themselves?

Black tailed prairie dogs

• 98% decline in North

America

• Candidate species for

Endangered Species Act

listing

• Translocating individuals

to boost small or

extirpated populations

• Low survival rates after

translocations

Prairie Dog

Antipredator Behavior

• Alarm calls denote certain predators

– Mammalian (e.g., coyotes)

– Hawks

– Snakes

• Different alarm calls refer to different

response behavior and urgency

Prairie Dog

Antipredator Behavior

• Pre-release predator training

for captive-born juveniles

– Paired presentation of

predators with appropriate

alarm calls

• Enhanced antipredator

behavior and increased

post-release survival

Shier & Owings 2006

Predator Reintroduction

• Wolves reintroduced in

areas in Wyoming after

30-year absence

• Moose calf death rate

increased

• But… tested moose that

lost calves to wolf

predation and showed

hypersensitivity to wolf

vocalizations

Berger et al. 2001

Animal Behavior and

Conservation

• Understanding behavior

can lead to better

conservation of wildlife

• Taking historic

information into account

may be important

Acknowledgements

Don Owings

Matt Rowe

Tim Caro

Jamie Cornelius

Annie Leonard

Terry Ord

George & Maria Clucas

Dick Coss

Doug Dinero

Tom Hahn

Ann Hedrick

Peter Marler

Lori Miyasato

Larry Rabin

Aaron Rundus

ABGG students 2002-2008,

Pat & Roy Arrowood, Stan Bursten,

Marian Bilheimer, Jenn DeBose,

Taylor Chapple, John Hammond,

Tyson Schmidt, Aysha Taff, 2008

Bodega Phylogenetics Workshop

(especially Brian O’Meara), Fred

Armstrong, Gwen Bachman,

Gretchen Baker, Duane Davis,

Karen Hughes, Michael Magnuson,

Phillip McClelland, Sonia Navarro

Perez, Richard Roy, Donna Stovall,

Renee West, Sebastian, Batman,

Sugar, the Celtic soccer team, and

the countless people who donated

shed snake skins

NSF

UC Davis Animal Behavior

Graduate Group

Animal Behaviour Society

American Society of

Mammalogy

UCMexus

UC Davis College of

Agricultural &

Environmental Sciences