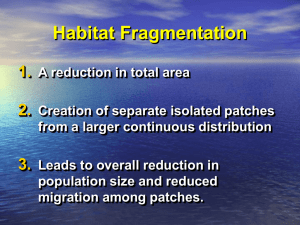

Habitat Fragmentation

Habitat Fragmentation

We have mostly made a mess of things. We have repeatedly destroyed natural environments, and even when we haven't destroyed them, we have fragmented them in ways which have had serious consequences for the survival of ecosystems and species.

What is Habitat Fragmentation?

Modern views (e.g. Fahrig 2003) take in two components; one is called fragmentation. They are:

1) habitat loss (destruction or conversion) and

2) habitat fragmentation, in which the habitat is broken apart after controlling for any habitat loss

Habitat loss almost always has strong negative effects on biodiversity, whereas habitat fragmentation usually produces weaker effects.

Fahrig (2003) suggests that the term fragmentation should be used to describe only the breaking apart of habitat.

This diagram represents habitat loss, even though it occurs through

‘fragmentation’.

Habitat loss can be distinguished from fragmentation…

In addition to habitat loss, fragmentation can result in:

1) increase in the number of patches;

2) decrease in patch sizes;

3) increase (or decrease, in resulting patches) in isolation of patches.

One of the important concerns in addressing fragmentation is the importance of scale.

Fragmentation may have differing impacts at the landscape scale when compared to effects within habitat patches. Fahrig, in her review, gave us some diagrammatic patterns to work from…

A Survey of Habitat Fragmentation Experiments

Before looking at a number of specific examples, I’ll first present some results from a meta-analysis of fragmentation (Debinski and Holt 2000).

Fragments varied in size from <1m 2 to 1000 ha, and replication from single fragments to 160 in a category.

Most experimental studies were performed in North

America and Europe. Others came from Brazilian tropical rain forest, African Serengeti plains,

Australian rain forest, northern Japanese forest, etc.

The questions generally fell into 6 categories:

• Was species richness related to area or to patch shape, as island biogeography/metapopulation biology suggest?

• Did species density or abundance increase with fragment area (or aspects of shape)?

• Were species interactions affected by fragmentation?

• How did edge effects affect what are termed

"ecosystem services"?

• How did corridors influence movement between fragments? And how did connectivity (in whatever form) influence species richness of connected fragments?

1) Species richness only increased as a function of fragment area in 6 of 14 studies that could be evaluated.

What happened in all those other studies?

There were clear explanations in most. For a short time, at most 1-2 years after fragment formation, species driven out by the change from habitat to matrix invade the remaining fragments and temporarily increase diversity.

In other cases edge species are able to survive in the increased edge area caused by fragmentation, and add to the species counts.

2) Abundance also declined in fragments in comparison to continuous habitat. Decreased abundance was seen in species from weevils to trees.

3) One of the problems in rejected studies was difference in sampling effort with patch size (see

Yamaura et al. 2008). Some apparently significant effects of size were negated when correction for effort was incorporated.

An analogy…

3. When considering interaction effects, predator-prey interactions were more successfully studied.

Fragmentation affects the predators' ability to rapidly find and concentrate in regions of prey abundance.

Different predator-prey systems function at different spatial scales.

One example: Aphids have more frequent outbreaks, escaping control by coccinelid beetle predators, in more fragmented landscapes.

4) Edge effects are commonly found, both in abiotic conditions and within the biological system. Abiotic effects include altered nutrient cycling and changes in the temperature, light, and relative humidity regimes within the fragments. Biotic effects include altered invasibility, recruitment, and the presence of species in edge habitats not likely to persist in continuous habitat.

Edge effects affect different species differently…

Yamaura et al.’s (2008) study separated birds, butterflies and forest trees into edge, neutral and core area species to determine which species were affected by area and patch shape in naturally occurring patches on Hokaido. Both area and shape affected interior species of birds and butterflies. Only area affected interior forest trees.

Forest interior birds woodland butterflies

Open ground butterflies (edge species) were affected significantly by shape – the more circular the patch the less edge per unit area, and fewer edge butterflies.

5) Corridors should enhance inter-fragment movement. In 4 of 5 studies that examined corridors, the movement of at least some species was enhanced.

The results were very species specific.

Corridors are controversial because they are rarely so wide as to incorporate a continuous path of core habitat. Therefore, they become prime places for predators and edge species to occupy

Now let’s consider a few examples of experimental fragmentation. Most of the results are remarkably similar though they come from very different communities.

One, Schmiegelow et al. (1997) comes from the boreal forest. The other, in an extensive series of papers, is about manipulated fragmentation in Brazilian tropical rainforest (Lovejoy et al 1984 is the first review).

The tropics first: Lovejoy used Brazilian requirements that 50% of areas of tropical forest intended for development had to be left forest.

An aerial photo of two of the isolated patches at

Manaus, Brazil

They made arrangements with developers to leave behind pre-marked tracts of different area and isolation to be followed after the clearing of surroundings. Replicate isolates over a size range from

1 to 1000 ha were studied prior to isolation, then followed afterward. A single 10,000 ha 'mainland‘ was also retained.

Bird density immediately after isolation showed a transient increase in density, lasting up to 200 days.

The authors describe this as a 'crowding effect'. The degree of crowding depended on the area cut and prior population density

Thereafter, density, measured as mist net captures per hour, declined to levels below pre-isolation numbers, but still relatively similar to equivalent areas not isolated.

Interestingly, on average residents prior to isolation do worse than those who move in. Diversity only declines. Within 5 months after the post-isolation sampling, the curve of species accumulation is asymptotic at a lower diversity.

Effects are not uniform over bird species. Two guilds are particularly suppressed following isolation: armyant followers, which feed on insects fleeing swarming army ants, and mixed species flocks of insectivores.

The former disappeared rapidly following isolation of

1 and 10 hectare fragments. The latter disappeared more slowly, over 1-2 years, from these smaller fragments.

The distance the fragments were separated from unaltered forest made a difference, which varied among taxa. For important pollinating insects (e.g. euglossine bees), pollination results indicated that 15 species would not cross 100m cleared strips. The population biology of at least 30 plant families will be/has been affected by reduced or lack of pollination. Dung and carrion feeding beetles responded similarly to a 100m barrier. Decomposition will be slowed.

Mammal species are also affected. Primate diversity went almost immediately to near 0 in isolates. Of preisolation estimates of 20 mammal species present, only 7 persisted in the isolated fragments. Here’s a table of size effects:

Species Intact forest 10 ha 1 ha

Marmosa parvidens + -

Didelphis marsupialis ++ -

-

+

Alouatta seniculus +++ +++ -

Cebus apella + -

Dasypus novemcinctus +++ +? -

Sciurus gilvigularis + + -

Oryzomys capito

Agouti paca

Tapirus terrestris

+ + +

++ -

+? -

-

Common names for some of these species are:

Alouatta

– red howler monkey,

Cebus - capuchin monkey, Sciurus - squirrel, Agouti - agouti, Dasypus armadillo, Tapirus - tapir.

red howler monkey capuchin monkey

Marmosa - opossum

Didelphis – another opossum

Cebus - brown capuchin

Oryzomys – rice rat

Agouti paca

Dasypus - armadillo tapir

Other lessons learned: Size of protected area cannot be the sole criterion. The Amazon forest project has, for example, discovered frogs with very critical breeding habitat. Without ecological knowledge and planning, reserve areas in Amazonia could protect large areas, but not incorporate this breeding habitat.

This was (and is) a single study site in the tropics

(there have been many papers published about it). Are the results identical in other tropical studies of fragmentation? Not exactly!

Avifaunal extinctions as a proportion of guilds in 5

Site neotropical rain forest sites.

Raptors Insectivores Frugivores

Brazil 54 74 57

Panama 22 22 16

Ecuador 56 18 33

Colombia 33 31 36

Puerto Rico 14 7 22

What are the mechanisms explaining extinctions following fragmentation in the temperate zone? The reasons cover an essentially identical spectrum of ideas. Here are the explanations:

1)Home range. Fragments may be too small to provide minimum home range requirements for particular species. Ivory-billed woodpeckers require from 6.5-

7.6 km 2 of bottom forest. European goshawks need

30-50 km 2 fragments. And mountain lions have a home range >400 km 2 .

2) Loss of habitat heterogeneity. The remaining mosaic of habitats may not include all types present before fragmentation. Small ponds may be necessary for some birds to nest and reproduce. Some species use different habitats during different seasons or at different points in their life cycles. Both (or more) habitat types must be present in a fragment for these species to persist. Again, open water is an obvious example for amphibian species.

3.Effects of habitat between fragments. The landscape between terrestrial fragments may be inhospitable, but may also be survivable. This could reduce effective isolation of fragments. However, the landscape can also be a source of species damaging to native populations of the fragments. Land development or second growth can affect the population sizes and migration among fragments for many species.

4) Edge effects. In addition to effects on songbirds from nest predators like cowbirds that come from edge areas, there are effects on plant communities as well. Seed rain in small fragments may, even at the core of the fragment, largely be constituted of edge species propagules.

Long-term study of one economically important palm, an edge species, found that edge effects even differ between established and young plants (Brum, et al. 2008). Large Oenocarpus (a date palm) increased in edge areas over 22 years, but not in interior forest. Seedlings and saplings did not respond in the same way.

Demographic patterns may, if this is not a unique result, not be simple in documenting edge effects.

5) Secondary extinctions. These are species losses traceable to modifications in the structure of interactions (competition, predation, mutualism) among species components of the unfragmented area that are determined by the fragmentation process. Omnivores controlled by top predators prior to fragmentation can become important nest predators in fragments, for example.

Now let’s consider Schmiegelow’s (1997) study of boreal forest. The experimental design is quite similar to the study of tropical forest fragmentation.

There were control areas demarcated in uncut boreal forest, isolated patches of boreal forest, and patches connected by 100m wide corridors to remaining forest. Each condition was represented by replicate patches of 1, 10, 40 and 100 ha.

Bird species were identified from point sampling stations in each patch both before forest cutting and for two years afterward.

What follows are the general results. Much of it parallels what was observed in tropical forest…

In most patches there was no significant change in bird species richness from before to the end of the 2 year period. There was crowding initially after cutting, as in tropical fragments. Bird species diversity depended on area (remember island biogeography) after cutting, decreasing in smaller patches. Since richness didn’t change, but diversity did, community structure was altered.

Abundance of species was related to migratory strategy. Neotropical migrants declined in both connected and isolated fragments. These and some resident species depend on ‘core’ forest, which is lost when patches are isolated and the central area is too close to the edge.

Fitting the basic species-area equation S = cA z

Species-area relationships (all species):

Controls Year

1993

1994

1995

Isolated 1993

1994

1995

Connected 1993

1994

1995 z

.42

.39

.38

.46

.42

.44

.40

.44

.25

c

.76

.76

.84

.70

.75

.74

.87

.78

1.02

However, in the smallest patches (1 ha) connected by corridors, diversity increased, apparently due to the movement in of transients displaced by harvesting, using the corridors to accumulate in the small patches.

Turnover rates (replacement of one species by another, even though richness remains unchanged) were higher in isolated than in connected fragments.

Changes in response to fragmentation were less dramatic here than in the tropics, though parallel in direction. Why? Probably because effects were followed for only 2 years and because the boreal forest is subject to more frequent disturbance than the tropics.

Anticipating upcoming lectures, there is one more consideration in evaluating fragmentation effects: how fragmentation affects the genetic diversity of remnant populations. We’ll consider two reviews:

DiBattista (2008) did a literature review of the genetic impacts of human-mediated environmental change.

One category was fragmentation.

Habitat fragmentation results in population subdivision into smaller, more discrete subunits within which genetic variation is likely to decrease due to genetic drift and inbreeding within the smaller subunit populations. At least that’s the a priori idea. Does it usually happen?

DiBattista used the number of alleles per locus and/or heterozygosity as measures of genetic diversity; the diversity was measured using isozyme and microsatellite data.

Microsatellites and allozyme data differed quantitatively, but not qualitatively. Microsatellites were more diverse. Both sources showed decreased diversity under fragmentation (as the type of disturbance). Considering microsatellite and allozyme data together, note the consistent differences in the table below, and how consistent the differences are…

Undisturbed Fragmented

Allozyme A 2.13

0.09

H e

1.56

0.09

H e

0.19

0.016

Microsatellite A 8.84

0.57

0.14

6.83

0.02

0.52

0.65

0.018

0.59

0.023

A is the mean number of alleles per locus.

H e is the expected heterozygosity.

These trends were observed across a variety of taxonomic groups. There were sufficient data to analyze mammals and plants as separate statistical groups. The data were particularly dramatic for mammals…

For mammals:

Allozyme A 2.75

0.46

H e

Undisturbed Fragmented

0.34

0.16

Microsatellite A 8.18

0.69

H e

1.43

0.13

0.11

0.051

6.17

0.54

0.65

0.026

0.59

0.029

The data for plants is qualitatively similar, but the differences (losses) as a fraction of undisturbed levels are smaller.

The second review is specific, produced by Aguilar et al. (2008) to plants. Some of the expected

(hypothesized) results:

1. Erosion of genetic variability (a general result)

2. Increased interpopulation genetic divergence due to increased random genetic drift and inbreeding, and reduced gene flow

3. a lower proportion of polymorphic loci and a reduction in the number of alleles per locus are expected within the fragments

4. If fragmentation conditions persist over successive generations, decreased heterozygosity due to random drift and increased inbreeding are expected, resulting in the accumulation of deleterious recessive alleles, lowering the fecundity of individuals, increasing seed/seedling mortality, and reducing the growth rate of individuals, eventually driving populations to extinction.

Because genetic erosion in fragmented habitats should be more pronounced after several generations, it is expected to find stronger negative effects on the adult generation of shortlived species compared to long-lived species.

5. The ploidy level of plants may influence the effects on genetic diversity due to fragmentation.

Polyploids, with ‘extra’ copies of genes, are less likely to lose locus heterozygosity as rapidly following isolation.

6. The loss of genetic variation may reduce a population’s ability to respond to future environmental change.

7. Sudden decreases in effective population sizes due to habitat fragmentation would then have stronger negative effects on within-population genetic diversity of outcrossing species compared to selfers.

8. Vector-pollinated and/or dispersed species will be strongly affected by the relative isolation compared to vector movement distances.

9. Common species are more susceptible to genetic loss than rare ones, since rare species already have a reduced genetic diversity.

These are all accepted hypotheses. What was found in this meta-analysis?

Whatever the source or explanation, the genetic losses that result from habitat fragmentation will prove to be an important consideration in designing conservation strategies.

References

Aguilar, R., M. Quesada, L. Ashworth, Y. Herrerias-Diego and J. Lobo. 2008. Genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation in plant populations: susceptible signals in plant traits and methodological approaches. Molecular Ecology 17:5177-5188.

Bierregaard, R.O.Jr., T.E. Lovejoy, V. Kapos, A.A. dos Santos and R.W. Hutchings.

1992. The biological dynamics of tropical rainforest fragments. Bioscience 42:859-866.

Brum, H.D., et al. 2008. Rainforest fragmentation and the demography of the economically important palm Oenocarpus bacaba in central Amazonia. Plant Ecology

199:209-215.

DiBattista, J.D. 2008. Patterns of genetic variation in anthropogenically impacted populations. Conservation Genetics 9:141-156.

Lovejoy, T.E., et al. 1984. Ecosystem decay of Amazon forest remnants. In Extinctions.

M.H. Nitecki, ed. Univ. of Chicago Press. pp. 295-325.

Lovejoy, T.E. et al. 1986. Edge and other effects of isolation on Amazon forest fragments. in Conservation Biology - The Science of Scarcity and Diversity. M.E.Soulé, ed. Sinauer, Sunderland, MA.

Wilcove, D.S., C.H. McLellan and A.P. Dobson. 1986. Habitat fragmentation in the temperate zone. in Conservation Biology - The Science of Scarcity and Diversity. M.E.

Soulé, ed. Sinauer, Sunderland, MA.

Schmiegelow, F.K.A.; C.S. Machtans; S.J. Hannon. 1997. Are Boreal Birds Resilient to

Forest Fragmentation? An Experimental Study of Short-Term Community Responses.

Ecology , Vol. 78, No. 6. (Sep., 1997), pp. 1914-1932.

Yamaura, Y., T. Kawahara, S. Iida and K. Ozaki. 2008. Relative importance of area and the shape of patches to the diversity of multiple taxa. Conservation Biology 22:1513-

1522.