Change in kinship and marriage systems

and its reflection in languages and genes

QuickTime™ and a

TIFF (LZW) decompressor

are needed to see this picture.

Patrick McConvell

AIATSIS/ANU

AUSTKIN PROJECT

http://austkin.pacific-credo.fr

Australian Research Council 2008-10. Harold Koch, Ian Keen(ANU)

Laurent Dousset (CREDO/CNRS) et al incl. McConvell (ANU)

QuickTime™ and a

TIFF (LZW) decompressor

are needed to see this picture.

AUSTKIN ON-LINE DATABASE

QuickTime™ and a

TIFF (LZW) decompressor

are needed to see this picture.

DYNAMICS OF HUNTER-GATHERER

LANGUAGE CHANGE PROJECT

NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION, USA 2008-11: Claire Bowern (Yale); Jane

Hill (Arizona); Pattie Epps (Texas Austin); Keith Hunley (New Mexico) et al. incl.

McConvell (ANU) [website not yet established]

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

How the languages of hunter-gatherer groups have changed and spread

Language is a basic element in human social identity and change and spread of languages

is a key aspect of human and social dynamics.

The spread of farming and languages associated with it has claimed a lot of recent

attention but very little corresponding work on the languages of hunter-gatherers.

What drives change and spread among hunter-gatherers? Are such processes are

fundamentally the same or different from what occurred after the farming revolution – a

relatively recent event in the history of humans.

Comparison of hunter-gatherers in North and South America and Australia

The project is interdisciplinary in using the results of biological anthropology and genetics in

conjunction with those of linguistics, to clarify what the relative contributions of migration

and language shift were to language spreads.

Among the linguistic data to be collected are vocabulary in the fields of plants and animals,

and kinship and social organization. These provide evidence of changes in human ecology

and social patterns respectively and relate to the disciplines of archeology and sociocultural anthropology, also represented in the project team, as well as to biological

anthropology since both nutrition and lifestyle, and marriage patterns can be reflected in

genetic trajectories.

HUNTER-GATHERER

LANGUAGE CHANGE

CASE STUDY AREAS:

NORTH AND SOUTH

AMERICA

HUNTER-GATHERER LANGUAGE CHANGE

CASE STUDY AREA: AUSTRALIA

Resurgence of interest in kinship and kinship change

The last decade has seen a resurgence of interest in long-term

patterns of change in kinship systems, with reworking of

structuralist ideas of ‘transformations’ which do not always lead to

actual historical hypotheses (Godelier, Trautmann and Tjon Sie Fat

eds.1998). There are also actual hypotheses about prehistorical

change emerging (or reemerging), both regional sequences and

general evolutionary patterns and constraints (eg Dziebel 2007;

James et al eds 2008).

Linguistic evidence of kinship change

A prominent theme in some of this work is the importance of

linguistic evidence (emphasised in many papers by the late Per

Hage and colleagues). Reconstruction of kinship terminologies

(systems) at various proto-language levels enables us to view

prehistoric systems and the changes they have undergone.

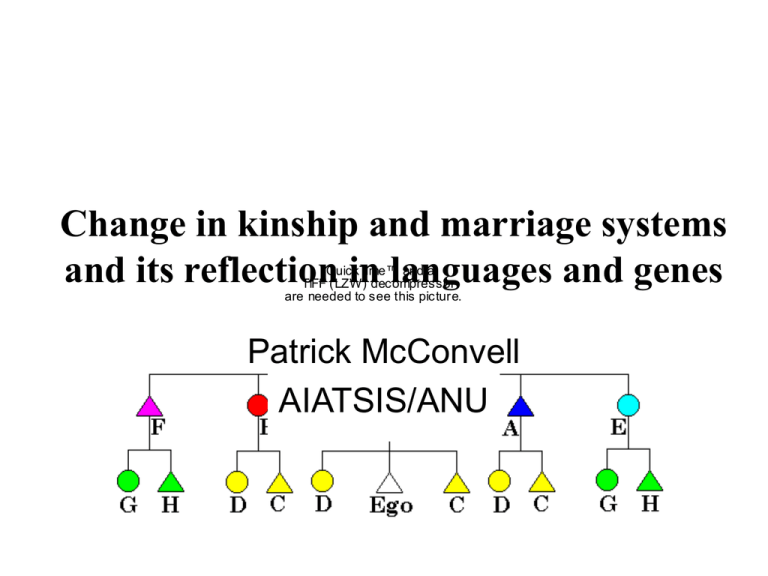

KINSHIP AND MARRIAGE

Relationships between marriage types and kinship systems

have been proposed throughout the history of anthropology

from Morgan on. These have often been framed in terms of

correlations between marriage patterns or rules and kinship

systems synchronically.

LINKED CHANGE IN KINSHIP AND MARRIAGE

There are also studies which attempt to show how diachronic

developments in marriage might have led to change in kinship

systems. Dole (1969) for instance argues that a change to

generational (‘Hawaiian’) terminology from Dravidian/Iroquois

cross-cousin terminology among the Kuikuru of Brazil

represents an adaptation to language group endogamy due to a

long-distance migration.

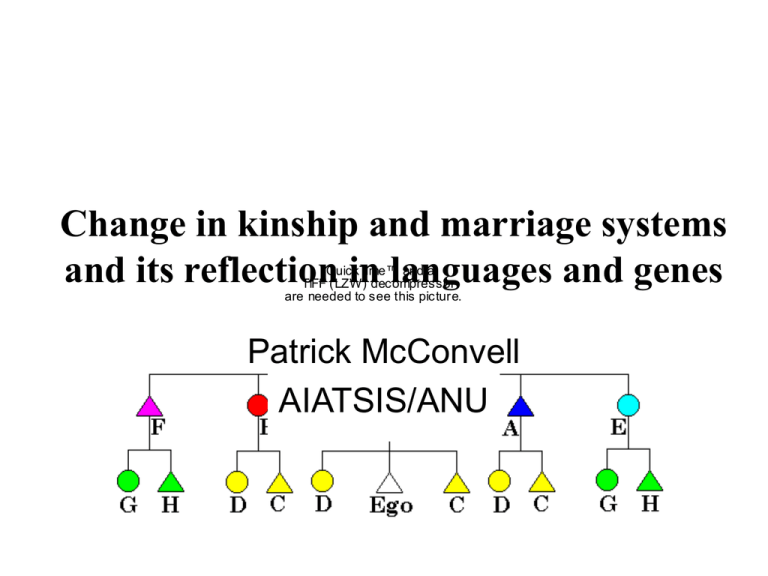

Dravidian endogamous circulation

FZ

Cross-cousin terms

same on both sides

and may be same

as ÔspouseÕ

F

Man marries motherÕs

brotherÕs daughter or

fatherÕs sisterÕs daughter

M

MB

Woman marries

motherÕs brotherÕs

son or fatherÕs

sisterÕs son

ÔDRAVIDIANÕ

BILATERAL

CROSSCOUSIN

MARRIAGE

With prescriptive

equations

Dravidian systems would generally tend to keep marriage

alliances in relatively tight closed loops.

SYSTEMS THAT DISPERSE ALLIANCES

The other kinds of marriage system which are known to develop from Dravidian

bilateral cross-cousin marriage have terminological structures distinctively

different from Dravidian. Some also tend to disperse marriage alliances

more widely in various ways. These include

1. Asymmetric cross-cousin marriage eg matrilateral, where

a man marries a (classificatory) MBD, not an FZD

2. Skewing systems eg Omaha where an MBD is classified

as a ‘mother’ and therefore usually unmarriageable

3. ‘Second cousin’ (Aranda) systems in Australia

4. (possibly) systems involving ‘marriage classes’ like

sections and subsections

In Australia, the development of Omaha skewing can be shown by linguistic

evidence to be involved in the transition to matriliateral marriage. Keen also

hypothesises that matrilateral systems are correlated with high polygyny, and

old men having young wives.

LOSS OF CROSS-PARALLEL DISTINCTIONS

As well as the loss of symmetry in marriage direction, a common feature

in both Australia and North America is the loss of an original system which

distinguishes between cross-cousins and parallel cousins (the latter

equated with siblings) in favour of one which suppresses or downgrades

this distinction. This seems to correlate with expansion of language

groups into tougher environments on both continents. Lower levels of

polygyny might be expected in this situation.

The loss of symmetry seems to correlate with what I have called

‘downstream spread’ and loss of cross-parallel distinctions with ‘upstream

spread’. Details of why these correlations are present still need to be

worked out.

Cross-parallel distinctions in grandparent terminology are also lost under

apparently similar circumstances yielding grandfather/grandmother

systems from systems which distinguished FF and MF and FM from MM,

eg in the Chiracahua variety of Apachean and inland Northern

Athapaskan; and in the ‘Luritja’ system of the Australian Western Desert.

MIGRATION AND LANGUAGE SHIFT

The individual ‘migration’ of spouses to post-marital residence

localities is different from the migration of whole groups. It may

be better to use ‘movement of spouses’ for the former.

Migration of groups can happen with or without significant

language shift. Groups may just live side by side without language

shift or one group may displace another physically without

language shift.

Language shift if it occurs can be from or to the migrating

language. It may occur in conjunction with high rates of

intermarriage or not. A likely hypothesis is that this conjunction is

common. If intermarriage and language shift cooccur, language

shift will accompany high gene flow and this may be sexasymmetric.

GENETIC PREDICTIONS ABOUT MIGRATION AND

LANGUAGE SHIFT

Language spread can occur through large-scale migrations or through language shift. In the

simplest migration scenario, marital exchange occurs between local groups subsequent to

the migration. The exchange will produce a correlation between the genetic and geographic

distances between groups…. The migration scenario can be tested by collecting genetic

data from the different groups and measuring the correlation between genetic and

geographic distances.

The hypothesis of language shift may be tested by collecting genetic data from many

groups in a region that speak both similar and different languages. Groups that experienced

language shift will be genetically closer to groups with which they share a more recently

common biological ancestry than to groups with which they share a language. The

hypothesis has previously been formally tested in South America using multidimensional

scaling (Cabana et al. 2006).

The predictions and tests of the migration and shift processes are fairly clear cut if groups

have persisted in the same region for considerable periods, if they have not moved much

within the region, if they are evenly distributed across the landscape, and if genetic

exchange is limited to geographic neighbors. These conditions are never met for long in

humans, but the tests can be adjusted to take into account aspects on population history

estimated from independent sources (e.g., archaeological data) and by taking into account

geographic features such as waterways.

“DOWNSTREAM”

Greater carrying

capacity

Initial

upstream

spread

100%

migration

“UPSTREAM”

Lesser carrying

capacity

“DOWNSTREAM”

Greater carrying

capacity

Range

expansion

Migration

“UPSTREAM”

Lesser carrying

capacity

Language shift

“DOWNSTREAM”

Greater carrying

capacity

High mobility

Dense

networks

Language

focussing

Low contact

influence

“UPSTREAM”

Lesser carrying

capacity

“DOWNSTREAM”

Greater carrying

capacity

Downstream

spread

Migration

“UPSTREAM”

Lesser carrying

capacity

Language shift

“DOWNSTREAM”

Greater carrying

capacity

RAIDS

INTERMARRIAGE

RITUAL TIES

Downstream

spread

Migration

“UPSTREAM”

Lesser carrying

capacity

SUBSTRATUM

Language shift

Genetics and marriage

Patrilocality and dispersal of mtDNA

There have been a number of studies of mitochondrial and Y-chromosome DNA

(female and male-linked respectively) which have linked wide distributions to

preferred post-marital residence patterns and resultant ‘migration’ of spouses. A

common pattern is the wide dispersal of mtDNA, linked to patrilocal residence, and

perhaps to certain marriage patterns.

•In other cases, the results reflect known historical events. For example,

colonizations consisting primarily of men have resulted in the introgression of

European Y-chromosomes—but not mitochondria—into native populations

•…patrilocal groups show more geographic structure in their Y-chromosomes,

while matrilocal groups have more geographically structured mitochondria.

(Wilkins & Marlow 2006:290)

•the ethnographic dataindicate that the transition to agriculture is associated with an

increase in patrilocality.We propose a model in which male and female migration

are similar over most of human history, and female-biased migration is a recent

phenomenon.

(Wilkins & Marlow 2006:291)

CLAIMS DISPUTED

This follows on claims by Marlow (2004) that hunter-gatherers

tend not to have bilateral descent as well as no strong bias in post

marital residence in contrast to agriculturalists. These hypotheses

are doubtful.

Wilkins & Marlow assume that there has been a broad change

towards more patrilocality over the course of (pre-) history due to

the change to agriculture.

However when we look at hunter-gatherer groups we can see not

only that there is variation in these patterns between them but also

that they go through processes of change which affect marriage

dispersal patterns and therefore distibution of genetic markers.

The connections [of kinship systems] with genetic variation are also worth

pursuing, particularly because different kinship systems may have different

consequences for patrilineally and matrilineally transmitted genes …

…the interaction between kinship as a social institution and population processes

like migration and diffusion may be a particularly rewarding topic for future

investigation. For example, prehistorians commonly argue that demic expansions

are driven by innovations in subsistence, especially domestication. But which

groups spread and both when and how they did is sometimes a function not just of

material technology but of social structure. Instead of kinship systems being

passively carried along by population expansions and diffusion like neutral genetic

poymorphisms,they may play an active role in these processes,which may in turn

feed back to influence kinship. This article has argued that demic expansions have

been associatedwith the spread of particular social systems; future research may

demonstrate that these social systems haveplayed some role in causing these

expansions. If so, then cultural anthropology’s long-standing interest in kinship

systems and their structural consequences may contributeto explaining some of

the major events in prehistory.

DOUG JONES (2003)

Kinship and Deep History: Exploring Connections between Culture Areas,

Genes, and Languages

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST 105(3):501–514.

Jones contd.

For Na Dene speakers in North America, …there is substantial agreement on

linguistic relationships and ancestral kinship systems, …

For New Guinea and Australia, the role of demic expansions and genetic and

cultural diffusion in the origin of population clusters, language families, and

culture areasis less certain, although a provisional case can be made for

parallel transmission. Australia is particularly interesting: Although not widely

known, there is quite suggestive genetic,linguistic, and archeological evidence

for a fairly recent (from about six k.y.a.) demic expansion. This obviously

may bear on the origin of the continent’s distinctive social organization.

[cites McConvell & Evans etc. on Pama-Nyungan expansion hypothesis]

KINSHIP IN NORTH AMERICA

Athapaskan &

Numic:

Cross-parallel

lost in outer

areas, then

lineal (Crow) in

origin area

QuickTime™ and a

TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor

are needed to see this picture.

Algonquian:

Cross-parallel

lost in outer

areas, then

lineal (Omaha)

in further

southern area

NUMIC

Ancient Mitochondrial DNA Evidence for Prehistoric

Population Movement: The Numic Expansion

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL

Frederika A. Kaestle and David Glenn Smith

ANTHROPOLOGY 115:1 Ğ12 (2001)

Suggests that genetics supports a migration scenario for Numic expansion in the main

but Cabana et al 2008 advocate a more rigorous method which may affect that finding

Proto-Numic ‘Kariera’

The four +2/-2 alternate generat ion terms and the two key +1

generation prescr iptive terms clearly imply that the Proto-Numic

kinship system was Kariera B (Dravidiana te)

+2/-2:

*kynu FF, mSC

*toko MF, mDC

*kaku MM fDC

*hu’ci~wi’ci FM, fSC

In the parental generati on, the prescriptive equations MB=spouses F,

FZ= spouse’s M are singled out:

+1:

*ata MB (FZH) EF mZC

*pahwa FZ (MBW) EM fBC

Gene flow across

linguistic boundaries in

Native North American

populations

Keith Hunley and

Jeffrey C. Long

PNAS February 1,

2005 vol. 102 no. 5

ATHAPASKAN

(Hunley & Long contd)

…a history of pervasive genetic exchange across linguistic boundaries. The distribution of mtDNA

haplogroups in the Apache and Navajo presents the clearest example. As shown in Fig. 4, the

distribution of the canonical Native American mtDNA haplogroups differs markedly between the

far North and the Southwest. Notably,mtDNA sequences belonging to haplogroup B are not

observed in the northern Na-Dene-attributed populations, and members of haplogroup C occur

rarely (Fig. 4). By contrast, mtDNA sequences in Southwestern non-Athabascan speakers are

characterized by the predominance of members of haplogroups B and C and the absence of

members of haplogroup A. The haplogroup configuration for non-Athabascan speakers in the

Southwest is exemplified in the present study by the Pima mtDNA sequences (Fig. 4) …The

Navajo and Apache possess many haplogroup A sequences typical of Northwestern

populations with languages attributed to the Na Dene language family. However, DNA

sequences belonging to haplogroups B and C are also common in the Navajo and Apache,

and these are most likely due to immigrants from the local non-Athabascan speaking

populations. …the pattern of genetic exchange is not reciprocal.A-group haplotypes would

have appeared in the Pima sample if they had absorbed a substantial number of Athabascanspeaking migrants. The pattern of asymmetrical genetic exchanges is allthe more interesting

given current mate exchange practices.Today, marriage practice in both the Western Apache

and Navajo is strongly matrilineal . On this basis, we would not expect to see the inclusion of

female lineages introduced from the surrounding non-Athabascan-speaking populations.

However,the practice of matrilineality in these populations is likely to have begun after the

Navajos and Apaches arrived in the Southwest(31). This practice makes it likely that the

haplogroup B and CmtDNA sequences carried in the Navajo and Apache today wereintroduced

early in their experience in the Southwest, and before the current cultural practices were initiated.

THIS IS PUZZLING…

•‘matrilineal’ refers to a type of descent not a type of marriage

•presumably this refers to a requirement that Apacheans need to have a mother

from the same group to be a member of a matriclan, in effect prohibiting men

marrying outside the group;

•not everyone is convinced that Apachean matrilineality is a product of late contact

with Pueblos; Dyen & Aberle argue it is old in Athapaskan

•matrilocality has been seen to be a response unifying a group after migration

(Divale 1974)

BUT IT IS AN INTERESTING TYPE OF MODEL

•it proposes a past cultural change in marriage which affects the pattern of gene

flow between groups

•the present-day gene distribution mainly reflects a previous period when gene flow

was higher, and putatively, a different marriage regime existed

•incidentally - this is not in the article - parallel types of argument can be drawn

from historical linguistics - kinship terminologies that reflect old states of affairs that

help us understand change in social practices

•generally however geneticists do not engage with this type of anthropological

linguistics

Jack Ives and Sally Rice (2006) Correpondences in

Archaeological, Genetic and Linguistic Evidence for

Apachean History

UCSB/MPI-EVA Language & Genes Workshop

Human biological data provide unambiguous evidence for this hypothesis that

Apachean ancestors came from the Subarctic, had a small founding population,

and followed a route southward that did not take them through the Great Basin

(e.g., Li et al. 2002; Malhi et al. 2003; Smith et al. 2000 . Both mtDNA

haplotype A and AL*Naskapi incidences confirm a northern origin for all

Athapaskan populations. Lower sequence variation for mtDNA haplotype A

among Apachean peoples, as well as the characteristics of Athabascan Severe

Combined Immunodeficiency Disorder and Athabascan Brainstem Dysgenesis

Syndrome, imply genetic bottlenecking in the Apachean past. AL*Naskapi is

absent among Numic speakers, but mtDNA haplotypes B and C among

Apachean speakers show that gene flow did take place with their immediate,

recent neighbours (Puebloan peoples for Navajo, Piman peoples for Apaches).

QuickTime™ and a

TIFF (LZW) decompressor

are needed to see this picture.

QuickTime™ and a

TIFF (LZW) decompressor

are needed to see this picture.

SOME POSSIBLE TRANSITIONS IN PAMA-NYUNGAN

KINSHIP SYSTEMS

Yolngu

>asymmetric

(matrilateral)

Karajarri

Kariyarra

Arrernte

Western

Desert

Cape York

Peninsula

?original

Kariera/Dravidian

>Aranda

(MMBDD/FFZDD

= wife)

>Luritja,

weakening

of crossness

NGUMPIN-YAPA

Ngumpin downstream spread

ARANDIC

‘THE ARANDA SCARP’ Tawny-hair

WESTERN DESERT DIALECTS

DRAVIDIAN TO MATRILATERAL

(‘Kariera’ to ‘Karadjeri’)

FZ

Crosscousin/spouse

terms different on

each sides ÔspouseÕ

F

Man marries motherÕs

brotherÕs daughter ONLY

M

MB

DRAVIDIAN

BECOMES

MATRILATERAL

With ÔrupturedÕ

prescriptive

equations

Woman marries

fatherÕs sisterÕs

son ONLY

KINSHIP AND MARRIAGE SYSTEMS IN CAPE YORK

PENINSULA AND N.E.ARNHEM LAND

10

ARNHEM

LAND

3

GULF OF

CARP ENTARIA

1

7

11

Ayapathu

4

CAPE YORK

P ENINSULA

9

5

6

7

2

8

NORTHERN

TERRITORY

QUEENSLAND

MAN

MARRIES

FZDD

MBD

ÔKaradjeriÕ

MyBD

FZD

MBD/ FZD

ÔKarieraÕ

There is a strong

genetic

connection

between

western CYP

and Yolngu of

NE Arnhem

Land (White

1997)

Ayapathu

(Rigsby)

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

kami

kamindhinhu

ngathi

ngathindhinhu

piipi

piinhayi

ngayunpa (poko)

paapa

kaali

thowe

muki

mukithu

wunhayi

karrki

yapi

RED=HAVE

YOLNGU

COGNATES

THOMSON (1972)

Kariera

Prescriptive

equations

Omaha

skewing

Cross cousin and uncle/aunt/

nephew/niece terms: the transition via

Omaha skewing

changes in meanings of terms CapeYork Peninsula >NE

Arnhem Land

FZ:

pim i

FZC /H/H

B:dhuwa

y

ZC :

dhu wa

F

EGO

MB+

muk

M

MB-:

gala

MBC /W /

W B:gala

y

The Indigenous

Australian Marriage

Paradox

Small-World Dynamics on a Continental Scale

Douglas R. White drwhite@uci.edu

Woodrow W. Denham wwdenham@gmail.com

White & Denham contd

Data - Problematic but Generally Accepted

• Ethnographers estimate that the

populations of Indigenous

Australian language groups were

consistently small, averaging

perhaps 500 people each.

• Classical models of Indigenous

Australian kinship systems

consistently embody

endogamous marriage as both a

norm and a logical requirement.

White & Denham contd

The Australian Paradox

• Paleodemographers argue that small reproductively

closed human populations are doomed due to stochastic

variations in birth rates and sex ratios.

• If both the population estimates and the models are right,

how did these small closed societies avoid extinction and

indeed persist in Australia for 40,000 years and more?

White & Denham contd

A Counter-Intuitive Approach

• We weaken the axiom for endogamy simply to a

preference, one that might vary through time.

• We argue that widespread restrictions on marriages,

especially when mates are scarce, may reduce choices

locally, but facilitate integration of populations globally

by forcing people to marry outside their own language

groups.

• Simply put, local restrictions encourage the

dispersion of marriages.

• [REPRODUCTIVE STRESS theory of changes in

marriage/kinship systems being developed by White

& Denham]

CONCLUSIONS

• Different kinship systems are correlated with different

marriage preferences and prescriptions

• Changes in kinship and marriage can be investigated using

linguistic reconstruction of terminologies and changes of

meaning of terms

• Different marriage systems are correlated with different

distributions of genes

• Some systems like ‘Dravidian’ bilateral cross-cousin

marriage tend to limit distribution of spouses (and genes)

while others disperse them

• The tendency for dispersal may be related to phases of

spread of peoples and languages :upstream with endogamy

and fission; downstream with exogamy, and language shift

• The proportion of language shift vs. pure migration, and its

direction. can be investigated using genetics