Can marine renewable installations provide a new niche

advertisement

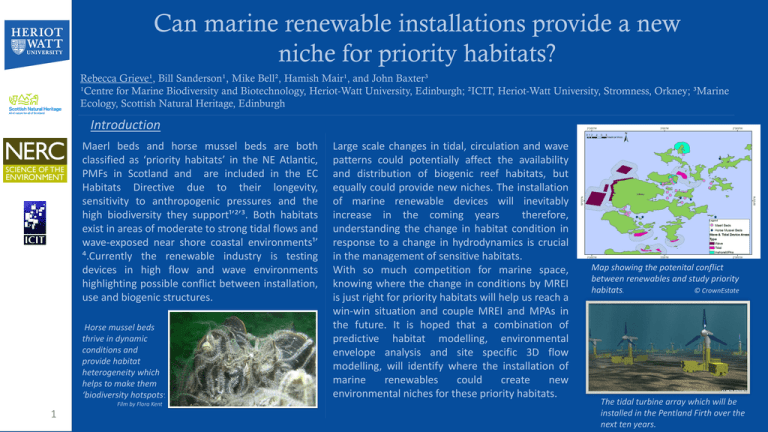

Can marine renewable installations provide a new niche for priority habitats? Rebecca Grieve¹, Bill Sanderson¹, Mike Bell², Hamish Mair¹, and John Baxter³ ¹Centre for Marine Biodiversity and Biotechnology, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh; ²ICIT, Heriot-Watt University, Stromness, Orkney; ³Marine Ecology, Scottish Natural Heritage, Edinburgh Introduction Maerl beds and horse mussel beds are both classified as ‘priority habitats’ in the NE Atlantic, PMFs in Scotland and are included in the EC Habitats Directive due to their longevity, sensitivity to anthropogenic pressures and the high biodiversity they support¹’²’³. Both habitats exist in areas of moderate to strong tidal flows and wave-exposed near shore coastal environments¹’ ⁴.Currently the renewable industry is testing devices in high flow and wave environments highlighting possible conflict between installation, use and biogenic structures. Horse mussel beds thrive in dynamic conditions and provide habitat heterogeneity which helps to make them ‘biodiversity hotspots’. Film by Flora Kent 1 Large scale changes in tidal, circulation and wave patterns could potentially affect the availability and distribution of biogenic reef habitats, but equally could provide new niches. The installation of marine renewable devices will inevitably increase in the coming years therefore, understanding the change in habitat condition in response to a change in hydrodynamics is crucial in the management of sensitive habitats. With so much competition for marine space, knowing where the change in conditions by MREI is just right for priority habitats will help us reach a win-win situation and couple MREI and MPAs in the future. It is hoped that a combination of predictive habitat modelling, environmental envelope analysis and site specific 3D flow modelling, will identify where the installation of marine renewables could create new environmental niches for these priority habitats. Map showing the potenital conflict between renewables and study priority habitats. © CrownEstate The tidal turbine array which will be installed in the Pentland Firth over the next ten years. 2 Predictive modelling can be used to identify how the distribution of habitats will change under different conditions such as in a changing climate and which environmental variables contribute most to the distribution of both maerl and horse mussel beds. Such a model, MAXENT, the maximum entropy predictive habitat model, uses presence data alongside a range of biophysical data to predict where a habitat or species is most likely to occur. It also indicates which variables contribute most to the distribution. Physical data such as temperature, salinity, current speed for the UK marine area is near impossible to collect as an individual therefore a collation of publically available data has been used in preliminary modelling attempts although this is of a low resolution. Similarly historical SNH diversity data has been collated for use in analysis. Preliminary Results Figure 1. Model output showing the variable contribution of factors in prediction of maerl beds. Figure 2. Modelled response of maerl in relation to current speed. Shaded area most powerful in prediction. * Variable % Contribution Landscape 36 Bathym. 24.2 Salinity Current speed Bot. temp Slope Fig 3. Infaunal diversity index (Shan.Wein Hlogₑ) in different tidal flow categories (m/s) ( * is sig dif. from 0.7m/s p<0.05) 23.9 10.1 4.9 1 Table 1. Imporatnce of envir. factors in predicting Horse mussel bed distribution MAXENT model output showed that bathymetry contributed most to maerl distribution, followed by landscape or substrate type with current speed as the factor which contributes least (AUC values 1-0.9, 0.9-0.7, 0.7-0.5 are high, moderate and low predictive power respectively) (Figure 1). A closer look shows that 0.101m/s is the most probable current speed range for maerl peaking at 0.2m/s (Fig2). A GLM indicated that there was no significant relationship between infaunal diversity and tidal flow across a range of maerl beds at varying depths around Scotland. Depth was more closely related to infaunal diversity. 0.2m/s had significantly higher infaunal diversity, number and abundance of species than the highest tidal values 0.7m/s (Figure 3). The predictive model output for Horse mussel beds indicated that current speed was a much more important factor in determining distribution (Table 1) than with maerl. However, substrate and bathymetry are both highest contributing factors Discussion & Next Steps The current results obtained with publically available physical data and biological data from SNH are helping to clarify the just the complex environmental characteristics that are needed to support such habitats and what makes them ‘biodiversity hotspots’. A survey being carried out on a maerl bed on the west coast of Scotland; investigating what physical and biological factors drive biodiversity. Understanding the link between the benthic community and hydrodynamics, as well as the response of biogenic reefs to changes in hydrodynamics will help to inform the most appropriate areas where marine renewable structures could potentially have a positive impact. The intention of this research is to provide evidence to support marine spatial planning, serving to enhance biodiversity and therefore help to achieve various national and European environmental and climate change targets. Further Acknowledgements To Kate Gormley for data and MAXENT/GIS expertise, to MASTS and ETP for recent funding awards which supported training and aspects of my research , to the HW dive team for their invaluable help and videography /photography skills, SNH for data. Photos – Rob cook 3 The environments requirements of priority habitats are complex and unlikely to be static at a small scale, therefore modelling with large low resolution data sets should be taken with caution and can only give us an indication of trends rather. More fine-scale physical data is currently being collected at specific maerl and horse mussel beds. Similarly habitats are being surveyed and material collected to enhance our knowledge of associated diversity and community. This data will be of a higher resolution than what is currently available, although at a much smaller scale and will make modelling more powerful. The beautiful maerl beds of Orkney, supporting a wide range of life in dynamic conditions which in the future could be protected alongside marine renewable developments. References ¹Birkett, D.A., Maggs, C.A., & Dring, M.J. 1998. Maërl (volume V). An overview of dynamic and sensitivity characteristics for conservation management of marine SACs. Scottish Association for Marine Science (UK Marine SACs Project). 116 pp. ²Gormley, K. S. G., Porter, J., Bell, M., Hull, A., & Sanderson, W. (2013). Predictive habitat modelling as a tool to assess the distribution and extent of an OSPAR priority habitat under a climate change scenario: Informing marine protected area designation. PLoS ONE, 8(7): e68263.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068263. ³Howson, C. M., Steel. L., Carruthers, M. & Gillham, K. 2012. Identification of Priority Marine Features in Scottish territorial waters Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 388 ⁴Rees I (2009) Assessment of Modiolus modiolus beds in the OSPAR area. Prepared on behalf of Joint Nature Conservation Committee.