Chapter 9

Labor Mobility

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

Labor Economics, 4th edition

Copyright © 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

9-3

Introduction

• Labor mobility is the mechanism that labor markets use to

improve the allocation of workers to firms

9-4

Geographic Labor Migration as Human

Capital Investment

• Mobility decisions are guided by comparing present value of

lifetime earnings in alternative employment opportunities

• A worker decides to move if the net gain from the move is

positive

- Improvements in economic opportunities available in a

destination (residence) increases (decreases) the net gains to

migration and raises (lowers) the likelihood a worker moves

- An increase in migration costs lowers the net gains to

migration, decreasing the probability a worker moves

• Migration occurs when there is a good chance the worker will

recoup his human capital investment

9-5

Internal Migration in the United States

• Probability of migration is sensitive to the income differential

between the destination and origin

• There is a positive correlation between improved employment

conditions and the probability of migration

• There is a negative correlation between the probability of

migration and distance, where distance is taken as a proxy for

migration costs

• There is a positive correlation between a worker’s educational

attainment and probability of migration

• Workers that have migrated are more likely to return to the

location of origin (return migration) and are more likely to

migrate again (repeat migration)

9-6

Probability of Migrating across State Lines in 20032004, by Age and Educational Attainment

8

Percent Migrating

6

College Graduates

4

2

High School Graduates

0

25

30

35

40

45

50

Age

55

60

65

70

75

9-7

Family Migration

• The family unit will move if the net gains to the family are

positive

• The optimal choice for a member of the family may not be

optimal for the family unit (and vice versa)

- Tied stayer – one who sacrifices better income opportunities

elsewhere because the partner is better off in their current

location

- Tied mover – one who moves with the partner even though

the employment outlook is better at their current location

9-8

Tied Movers and Tied Stayers

Private Gains to

Husband (PVH)

B

10,000

Y

C

A

-10,000

10,000

Private Gains to

Wife (PVW)

D

F

-10,000

X

E

PVH + PVW = 0

If the husband were single, he

would migrate whenever DPVH >

0 (or areas A, B, and C). If the

wife were single, she would

migrate whenever DPVW > 0 (or

areas C, D, and E). The family

migrates when the sum of the

private gains is positive (or areas

B, C, and D). In area D, the

husband would not move if he

were single, but moves as part of

the family, making him a tied

mover. In area E, the wife would

move if she were single, but does

not move as part of the family,

making her a tied stayer.

9-9

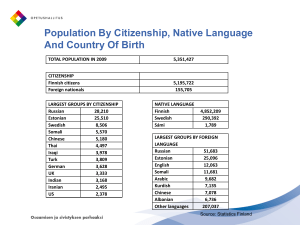

Immigration in the United States

- There has been resurgence of immigration to the

United States in recent decades

- The United States receives the largest immigrant flow

in the world

- The mix of countries of origin has altered substantially

• For example, in the 1950s only 6% of immigrants were

from Asia, whereas now 31% originated in Asia

9 - 10

Legal Immigration to the United States

by Decade, 1820-2000

Number of legal immigrants

(in millions)

10

8

6

4

2

0

1810s

1830s

1850s

1870s

1890s

1910s

Decade

1930s

1950s

1970s

1990s

9 - 11

Immigrant Performance in the U.S.

Labor Market

• Immigrants who can adapt well and are successful in new jobs

can make a significant contribution to economic growth

• The economic impact of immigration will depend on the skill

composition of the immigrant flow

9 - 12

The Age-Earnings Profiles of Immigrant

and Native Men in the Cross Section

Annual Earnings

(1970 Dollars)

9,000

Immigrants

8,000

Natives

7,000

6,000

5,000

4,000

20

25

30

35

40

45

Age

50

55

60

65

9 - 13

The Decision to Immigrate

• There will be a dispersion in skills among national-origin

groups because different types of immigrants come from

different countries

• The general rule: workers decide to immigrate if U.S. earnings

exceed earnings in the source country

9 - 14

Cohort Effects and the Immigrant AgeEarnings Profile

D ollars

C

P

1960 W ave

P*

P

Q

1980 W ave

and N atives

Q*

Q

R

2000 W ave

R

C

R*

20

40

60

A ge

The cross-sectional

age-earnings profile

erroneously

suggests that

immigrant earnings

grow faster than

those of natives.

9 - 15

The Wage Differential between Immigrant

and Native Men at Time of Entry

0

Log wage gap

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

1955-1959

1965-1969

1975-1979

Year of entry

1985-1989

1995-2000

9 - 16

Evolution of Wages for Specific Immigrant

Cohorts over the Life Cycle

Relative wage of immigrants who arrived

when they were 25-34 years old

0.1

Arrived in 1955-59

Log wage gap

0

-0.1

Arrived in 1965-69

-0.2

Arrived in 1975-79

-0.3

-0.4

1960

1970

1980

Year

Arrived in 1985-89

1990

2000

9 - 17

Roy Model

• This model considers the skill composition of workers in the

source country

- Positive selection – immigrants who are very skilled do

well in the U.S.

- Negative selection – immigrants who are unskilled do not

do well in the U.S.

- The relative payoff for skills across countries determines

the skill composition of the immigrants

9 - 18

The Distribution of Skills in the Source

Country

Frequency

Negatively-Selected

Immigrant Flow

Positively-Selected

Immigrant Flow

sN

sP

Skills

The distribution of skills in the source country gives the frequency of

workers in each skill level. If immigrants have above-average skills,

the immigrant flow is positively selected. If immigrants have belowaverage skills, the immigrant flow is negatively selected.

9 - 19

Policy Application: The Economic

Benefits of Migration

• The immigrant surplus is a measure of the increase in national

income that occurs as a result of immigrants (and the surplus

accrues to natives)

• Immigration raises national income by more than it costs to

employ them

9 - 20

The Self-Selection of the Immigrant

Flow

Dollars

Dollars

Positive Selection

Source

Country

U.S.

U.S.

Source

Country

Do Not

Move

Move

sP

(a) Positive selection

Do Not

Move

Move

Skills

sN

(b) Negative selection

Skills

9 - 21

The Impact of a Decline in U.S. Incomes

Dollars

Dollars

U.S.

Source

Country

U.S.

Source

Country

sP

(a) Positive selection

Skills

sN

sN

(b) Negative selection

Skills

9 - 22

Earnings Mobility between 1st and 2nd

Generations of Americans, 1970-2000

Relative wage, 2nd generation, 2000

0.6

Poland

Philippines

Cuba

Italy

Belgium

UK

China

India

Germany

Sweden

0

Honduras

Mexico

Dominican

Republic

Haiti

-0.6

-0.4

0

Relative wage, 1st generation, 1970

0.4

9 - 23

Job Turnover: Some Stylized Facts

• Newly hired workers tend to leave their jobs within 24 months

of hire, while workers with more seniority rarely leave their

jobs

• There is strong negative correlation between a worker’s age and

the probability of job separation

• The decline in the quit rate fits with the hypothesis that labor

turnover is a human capital investment

• Older workers have a smaller payoff period to recoup the costs

associated with job search,they are less likely to move

• The rate of job loss is highest among the least educated workers

9 - 24

The Job Match

• Each particular pairing of a worker and employer has its own

unique value

• Workers and firms can improve their situation by shopping for

a better job match

• Efficient turnover is the mechanism by which workers and

firms correct matching errors to obtain a better and more

efficient allocation of resources

9 - 25

Specific Training and Turnover

• When a given workers receives specific training, his

productivity improves only at the current firm

• This implies there should be a negative correlation between the

probability of job separation and job seniority

- As age increases, the probability of job separation decreases

9 - 26

Job Turnover and the Age-Earnings

Profile

• Young people who quit often experience substantial increases in

their wages

• Workers who are laid off often experience wage cuts

• A worker’s earnings depend on total labor market experience

and seniority on the current job

• Workers with good match employment will have low

probabilities of job separation and these workers will tend to

have seniority on the job

9 - 27

Probability of Job Turnover over a 2-Year

Period for Young and Older Workers

Young Workers

0.8

Probability

0.6

Separations

0.4

Quits

0.2

Layoffs

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Years on the Job

Older Workers

0.5

Probability

0.4

Separations

0.3

Quits

0.2

0.1

Layoffs

0

0

5

10

15

Years on the Job

20

25

9 - 28

Incidence of Long-Term Employment

Relationships, 1979-1996

35

30

Percent

Men

25

20

15

Women

10

1975

1980

1985

1990

Year

1995

2000

9 - 29

The Rate of Job Loss in the United

States, 1981-2001

20

High school dropouts

Percent

16

12

All workers

8

College graduates

4

0

1981-83 1983-85 1985-87 1987-89 1989-91 1991-93 1993-95 1995-97 1997-99 1999-01

Year

9 - 30

Specific Training and the Probability of

Job Separation for a Given Worker

Probability

of

separation

Seniority

If a worker acquires specific

training as he accumulates

more seniority, the

probability that the worker

will separate from the job

declines over time. The

probability of job separation

then exhibits negative state

dependence; it is lower the

longer the worker has been

in a particular employment

state.

9 - 31

Impact of Job Mobility on Age-Earnings

Profile

Wage

Stayers

Movers

Quit

t1

Quit

Layoff

t2

t3

Age

The age-earnings profile of

movers is discontinuous,

shifting up when they quit

and shifting down when

they are laid off. Long jobs

encourage firms and

workers to invest in

specific training, and

steepen the age-earnings

profile. As a result, stayers

will have a steeper ageearnings profile within any

given job.

9 - 32

End of Chapter 9