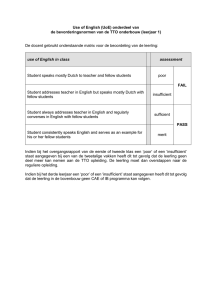

Voorstudie TPO - Europees Platform

advertisement