Manifest Destiny - Marion County Public Schools

advertisement

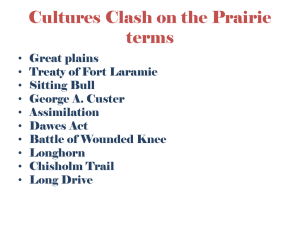

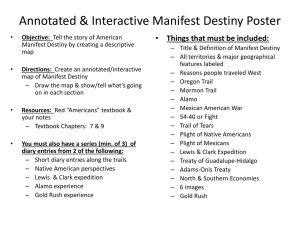

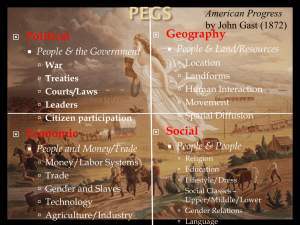

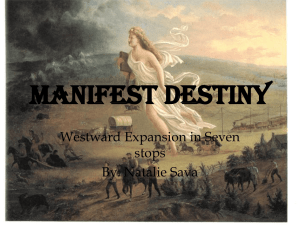

Manifest Destiny or Destruction Visual Discovery Teacher’s Guide Overview This Visual Discovery introduces students to some events associated with the fulfillment of Manifest Destiny. Students will view and discuss a series of seven slides that introduces them to the differing cultures and conflicts that existed between settlers and Native Americans. Students respond to a series of critical thinking questions about each slide, record, notes, and interact with the images. Preview Before beginning the lesson, have students listen to “Sweet Betsy from Pike.” After hearing the recording, have students share their comments and feelings about the song. Share with the students the fact that although a children’s song, “Sweet Betsy from Pike” is a song rich with history about the experiences for pioneers who dared make the adventure west in the 1800’s. After discussing student feelings, reintroduce the song, and have students listen to the song and follow along with the lyrics. At the end, have students answer the Discussion questions in Slide 6 in Manifest Destiny or Destruction? Slide Presentation. (Note: the song has been imbedded in to the slide and should start automatically in slides 3 and 4 of the Manifest Destiny or Destruction? Visual Discovery Slide Presentation). Before Class Make photocopies of Slides 10 and 11 an excerpt from Letters from a Woman Homesteader, “ A busy, happy summer.” Procedures 1. Tell students that they will now see a series of slides that will introduce them to some events in the fulfillment of Manifest Destiny. Students will be expected to view each slide carefully and be prepared to answer a series of questions you will ask. 2. Introduce the lesson by showing students Image 1: The Culture of the Plains Indians, which shows a photograph by John C. H. Grabill and the great hostile Lakota Sioux camp (Slide 7 of the Manifest Destiny or Destruction? Visual Discovery Slide Presentation). Tell the students to examine the picture carefully, and •Before you discuss the image, carefully select students who will be serious but comfortable acting in front of the class. Briefly explain that after the image is discussed, you will ask volunteers to come forward, assume the position and facial expression of one of four characters in the image, and answer from the perspective of the character. • Tell students that as you cover the information from the image they should be thinking about thoughts, feelings, or sensations that each of the four characters would have been experiencing at the time of the photograph to be able to perform the “Talking Statue” act-it-out. •After you have discussed the image, have students performing the act-it-out assume their spots. Tell the audience where the scene takes place. Assume the role of the “on-the scene reporter” and interview the characters by asking their names, tribe affiliations, and their thoughts, feelings, or sensations at the time of the photograph. •Thank the actors and have the audience applaud a they return to their seats. 4. For image 7, perform the “Reading for Enrichment” an excerpt from Letters from a Woman Homesteader, “ A busy, happy summer” after the image is discussed. In a read-out-loud, have students read the excerpt. After the reading, perform the follow up questions found in Slide 9 of the Manifest Destiny or Destruction? Teacher’s Guide. Processing Assignment Have students make an acrostic poem using the word “Old West” that describes their personal perspective on the unit theme question found in Slide 2 of the Manifest Destiny or Destruction? Visual Discovery Slide Presentation. An acrostic is a poem, where the first letter of every sentence is the is a letter from the theme word(s). The sentences work together to develop a poem that may or may not rhyme, but delivers a powerful way for students to process information related to a class topic. Have students decide if the closing of the West meant the fulfillment of our “Destiny” or the destruction of a legacy. Have students include three or more illustrations related to context, and use five or more colors. Image 1: The Culture of the Plains Indians What do you see here? Where was this picture taken? How would you describe this area? About how many settlements do you see? Photographed in this image by John C. H. Grabill, you see Villa of Brule the great hostile Lakota Sioux camp on River Brule near Pine Ridge, South Dakota. Image illustrates a Lakota tipi camp in background in 1891; horses at a White Clay Creek watering hole in foreground. Life on the Plains for Native Americans meant living in the Great Plains—grasslands in west-central portion of the U.S., where tribes were nomadic hunting and gathering. Horses and guns lead most Plains tribes to nomadic life by mid1700s. Trespassing others’ hunting lands caused war. Buffalo provided many basic needs: hides used for teepees, clothes, blankets; meat used for jerky, pemmican. Family Life for the Plains Indians meant forming family groups with ties to other bands that spoke the same language. Having roles meant men were hunters and warriors; women butchered meat, prepared hides. Natives believed in powerful spirits that control natural world. Men or women could become shamans. Children learned through myths, stories, games, example. Communal life meant leaders ruled by counsel. Cultures clashed as beliefs over land use conflicted. Native Americans thought land could not be owned; whereas settlers wanted to own land. Settlers thought natives forfeited land because did not improve it, and also considered land unsettled as ripe for migrants to go west to claim it. The lure of gold in 1858 drew tens of thousands to Colorado, where tiny frontier towns set up mining camps and filthy ramshackle dwellings for fortune seekers of different cultures and races. Image 2: Settlers Move West to Farm What do you see here? What seems to be happening in this image? Why are the buffalo running? How does this image represent irony? Who might the buffalo represent? Train? In this image you see Frank Leslie drawing from his Illustrated Newspaper, June, 1871. When the railroad pushed westward through the plains, buffalo were often shot for sport as the trains passed by, carcasses left to rot upon the prairie. Railroads opened the West. Between 1850–1871, huge land grants were given to railroads for laying track in the West. In the 1860s, the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads began constructing the nation’s first transcontinental railway. The Central Pacific headed east from California and the Union Pacific headed west from Nebraska. They built right past one another ant eventually met in Promontory Point, Utah. By the 1880s, 5 transcontinental railroads were completed in the U.S. Railroads sold land to farmers, and attracted many European immigrants. Railroad, state agents, and speculators profited. In the end, only 10% of land went to families. The government further supported settlement with the 1862 Homestead Act, which offered 160 acres free to any head of household. Between 1862–1900, up to 600,000 families settled out West. Settlers include the Exodusters, or Southern African-American settlers in Kansas. Image 3: Government Restricts Native Americans What do you see here? What information does the map show? Why were Native Americans being moved around? Who was responsible for this mass migration? About how much land did Native Americans loose by 1894? Retain? This image represents lands lost by Native Americans to the U.S. government from 1850-1990. Indian tribes both retreated and were removed from major areas of United States settlement in moves throughout the decades of the 19th century. By the Civil War, the most numerous tribes were west of the Mississippi River. Railroads influenced government policy. In 1834, government designated Great Plains as one huge reservation. In the 1850s, treaties defined specific boundaries for each tribe. The Bozeman Trail crossed Sioux hunting grounds in the Bighorn Mountains. Sioux Chief, Red Cloud unsuccessfully asked for an end to settlements along the trail. In December 1866, Crazy Horse ambushed federal troops at Lodge Trail Ridge killing 80 soldiers in what came to be know as the Fetterman Massacre. Skirmishes continued until the government agreed to close the trail with the Treaty of Fort Laramie. The Sioux were moved to a reservation in Missouri. Sitting Bull, leader of Hunkpapa Sioux, did not sign the treaty. Image 4: Bloody Battles Continue What do you see here? Why are these people be dancing? Does the dance look threatening? Why? Why not? How might these people be feeling? In this image you see an account of the Ghost Dance in the late 1800’s . The Ghost Dance was a religious movement incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. The traditional ritual used in the Ghost Dance has been used by many Native Americans since prehistoric times, but was first performed in accordance with Jack Wilson's teachings among the Nevada Paiute in 1889. At the core of the movement was Wilson’s prophecy of a peaceful end to white American expansion . One of the most tragic events occurred in 1864 in what came to be know as the Massacre at Sand Creek. Troops killed over 150 Cheyenne, Arapaho at the Sand Creek winter camp. Since 1868, the Kiowa and Comanche had engaged in 6 years of raiding that finally led to the Red River War in 1874– 1875. The U. S. Army crushes resistance on Plains by herding friendly tribes onto reservations and killing all others. In 1876, Sitting Bull had vision of war at a sun dance. Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Gall crushed Colonel George A. Custer’s troops at the Little Big Horn River in what came to be known as Custer’s Last Stand. By late 1876, Sioux were defeated. Some take refuge in Canada. With his people starving; Sitting Bull surrendered 1881. The Sioux continued to suffer from poverty and disease. In response as they began practicing a ritual called the Ghost Dance, a ritual to regain lost lands. The ritual spread among 25,000 Sioux on Dakota reservation. The ritual alarmed military leaders. In December 1890, they ordered the arrest of Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull is killed when police try to arrest him. The Seventh Cavalry took about 350 Sioux to Wounded Knee Creek. The following morning as troops tried to disarm the Sioux, the cavalry opened fire when a shot rang out and killed 300 unarmed Native Americans. The battle ended the Indian wars, and the Sioux dream of regaining old life. Image 5: Demand for Beef Grows What do you see here? Who are these men and what are they doing? How would you describe their type of work? Who might they work for? In this image, you see cowhands roping a calf at the legendary 15,500 acre King Ranch (established in 1853) in Rincon de Santa Gertrudis, Texas. After Civil War demand for meat increased in rapidly growing cities. American settlers learned to manage large herds from Mexican vaqueros. They adopted the way of life, clothing, and vocabulary. The Texas longhorns was the sturdy, short-tempered breed of choice originally brought over brought by the Spanish. Although cowboys were not in demand until railroads reached the Great Plains, cattlemen established cow towns, or shipping yards where trails and rail lines met. Trails like the Chisholm Trail became the major cattle route from San Antonio to Kansas. A cowboy’s life was not the sort of seen in Hollywood. A day’s work consisted of 10–14 hours on ranch; 14 or more on trail. Cowboys were expert riders and ropers alert for the many dangers that could have harmed or upset the cattle. Cowboys were in the saddle dawn to dusk, slept on ground, and bathed in rivers. Between 1866–1885, there were in excess of 55,000 cowboys on plains. 25% were African American and 12% were Mexican. A cowboy’s job consisted of many things. But more importantly was the spring roundup where longhorns were found in the open range, herded into corrals, separated, and marked with own ranch’s brand. The cattle were then herded for the long drive to the shipping yard, which could last about 3 months. As ranching became big business, the cattle frontier met its end as overgrazing and bad weather from 1883 to 1887 destroyed whole herds. The wide open range ended with barbed wire, turning the open range into separate ranches. Image 6: The Government Supports Assimilation What do you see here? Who are these kids? How old are they? Describe their mood. What might have these boys been feeling at the time of this photograph? In this photograph by J.N. Choate, you see a group of boys dressed in cadet uniforms at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania in 1880. Founded in 1879 by Captain Richard Henry Pratt, the first off-reservation boarding school became a model for schools attempting forcibly assimilate Native American children from 140 tribes into the majority culture of the United States. In 1881, writer Helen Hunt Jackson exposed the government’s many broken promises in A Century of Dishonor. At the same time many sympathizers supported Assimilation, where natives were forced to give up their way of life and join white culture. In 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Act to “Americanize” natives and break up reservations. The law promised to give land to individual Native Americans, and sell remainder of land to settlers. Proceed were to be given to Natives for farm implements. In the end, Native Americans received only 1/3 of land and no money. Perhaps the most significant blow to Naïve Americans was the destruction of buffalo as tourists and fur traders shot for sport with the full support of General Phillip Sheridan, who knew that the decimation meant the destruction of the Native American’s main source for food, clothing, shelter, and fuel. In 1800, 65 million buffalo roamed the plains. In 1890 fewer than 1,000 buffalo remained on the Plains. After you have finished reviewing all of the material and students have finished writing their notes, ask for 4 volunteers to step into character and Act-it-Out using “Talking Statues to demonstrate what these boys may have been thinking during their stay at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Image 7: Settlers Meet the Challenges of the Plains What do you see here? Describe the scene? Where was this photo taken? Why would women choose this type of lifestyle? How might they be feeling? In this photograph by K.D. Butcher, the four Chrisman sisters are lined up at their first homestead in 1887. The Chrisman sisters lived near the Goheen settlement on Lieban Creek in Custer County. Lizzie Chrisman filed the first homestead claim in 1887. Lutie Chrisman filed her claim the following year. The sisters took turns living with each other so they could fulfill the residence requirements without living alone. The other two sisters, Hattie and Jennie Ruth, had to wait until they came of age to file. Unfortunately all the land was gone before the youngest sister was old enough to file, but all four were well-known members of the community. Settlers faced many challenges with life in the Plains. From droughts to blizzards, floods, fire, locust plagues, and raids, the population grew from 1% in in 1850 to about 30% at the end of the century. Since trees were scarce, many settlers made dugouts, homes dug into the sides of ravines or hills. In the plains, settlers made soddies or sod homes by stacking blocks of turf. Soddies were warm in the winter and cool in the summer. However, they were small, offered little light, and were havens for pests. Although fireproof, they leaked when it rained. Homesteaders virtually lived alone, and were virtually self-sufficient. Women often worked beside men doing men’s work—plowing, harvesting, and shearing sheep. They also performed traditional work like carding wool, making soap, and canning vegetables. They were also skilled in doctoring ailments and injuries, and were involved in community work sponsoring schools and churches. Reading for enrichment. Read "A BUSY, HAPPY SUMMER" September 11, 1909, and have students answer the following questions. Who was Elinore Rupert writing to? What does Elinore Rupert do for a living? Describe the purpose of the letter? How would you characterize her work ethic? How does Elinore Rupert demonstrate her resourcefulness? Why might "A BUSY, HAPPY SUMMER" September 11, 1909. The writer of the following letters is a young woman who lost her husband in a railroad accident and went to Denver to seek support for herself and her two-year-old daughter, Jerrine. Turning her hand to the nearest work, she went out by the day as house-cleaner and laundress. Later, seeking to better herself, she accepted employment as a housekeeper for a well-to-do Scotch cattle-man, Mr. Stewart, who had taken up a quarter-section in Wyoming. The letters, written through several years to a former employer in Denver, tell the story of her new life in the new country. They are genuine letters, and are printed as written, except for occasional omissions and the alteration of some of the names. May 1914. DEAR MRS. CONEY, -This has been for me the busiest, happiest summer I can remember. I have worked very hard, but it has been work that I really enjoy. Help of any kind is very hard to get here, and Mr. Stewart had been too confident of getting men, so that haying caught him with too few men to put up the hay. He had no man to run the mower and he couldn't run both the mower and the stacker, so you can fancy what a place he was in. I don't know that I ever told you, but my parents died within a year of each other and left six of us to shift for ourselves. Our people offered to take one here and there among them until we should all have a place, but we refused to be raised on the halves and so arranged to stay at Grandmother's and keep together. Well, we had no money to hire men to do our work, so had to learn to do it ourselves. Consequently I learned to do many things which girls more fortunately situated don't even know have to be done. Among the things I learned to do was the way to run a mowing-machine. It cost me many bitter tears because I got sunburned, and my hands were hard, rough, and stained with machine oil, and I used to wonder how any Prince Charming could overlook all that in any girl he came to. For all I had ever read of the Prince had to do with his "reverently kissing her lily-white hand," or doing some other fool trick with a hand as white as a snowflake. Well, when my Prince showed up he didn't lose much time in letting me know that "Barkis was willing," and I wrapped my hands in my old checked apron and took him up before he could catch his breath. Then there was no more mowing, and I almost forgot that I knew how until Mr. Stewart got into such a panic. If he put a man to mow, it kept them all idle at the stacker, and he just couldn't get enough men. I was afraid to tell him I could mow for fear he would forbid me to do so. But one morning, when he was chasing a last hope of help, I went down to the barn, took out the horses, and went to mowing. I had enough cut before he got back to show him I knew how, and as he came back manless he was delighted as well as surprised. I was glad because I really like to mow, and besides that, I am adding feathers to my cap in a surprising way. When you see me again you will think I am wearing a feather duster, but it is only that I have been said to have almost as much sense as a "mon," and that is an honor I never aspired to, even in my wildest dreams. I have done most of my cooking at night, have milked seven cows every day, and have done all the hay-cutting, so you see I have been working. But I have found time to put up thirty pints of jelly and the same amount of jam for myself. I used wild fruits, gooseberries, currants, raspberries, and cherries. I have almost two gallons of the cherry butter, and I think it is delicious. I wish I could get some of it to you, I am sure you would like it. We began haying July 5 and finished September 8. After working so hard and so steadily I decided on a day off, so yesterday I saddled the pony, took a few things I needed, and Jerrine and I fared forth. Baby can ride behind quite well. We got away by sunup and a glorious day we had. We followed a stream higher up into the mountains and the air was so keen and clear at first we had on our coats. There was a tang of sage and of pine in the air, and our horse was midside deep in rabbit-brush, a shrub just covered with flowers that look and smell like goldenrod. The blue distance promised many alluring adventures, so we went along singing and simply gulping in summer. Occasionally a bunch of sage chickens would fly up out of the sagebrush, or a jack rabbit would leap out. Once we saw a bunch of antelope gallop over a hill, but we were out just to be out, and game didn't tempt us. I started, though, to have just as good a time as possible, so I had a fish-hook in my knapsack. Presently, about noon, we came to a little dell where the grass was as soft and as green as a lawn. The creek kept right up against the hills on one side and there were groves of quaking asp and cottonwoods that made shade, and service-bushes and birches that shut off the ugly hills on the other side. We dismounted and prepared to noon. We caught a few grasshoppers and I cut a birch pole for a rod. The trout are so beautiful now, their sides are so silvery, with dashes of old rose and orange, their speckles are so black, while their backs look as if they had been sprinkled with gold-dust. They bite so well that it doesn't require any especial skill or tackle to catch plenty for a meal in a few minutes. In a little while I went back to where I had left my pony browsing, with eight beauties. We made a fire first, then I dressed my trout while it was burning down to a nice bed of coals. I had brought a frying-pan and a bottle of lard, salt, and buttered bread. We gathered a few service-berries, our trout were soon browned, and with water, clear, and as cold as ice, we had a feast. The quaking aspens are beginning to turn yellow, but no leaves have fallen. Their shadows dimpled and twinkled over the grass like happy children. The sound of the dashing, roaring water kept inviting me to cast for trout, but I didn't want to carry them so far, so we rested until the sun was getting low and then started for home, with the song of the locusts in our ears warning us that the melancholy days are almost here. We would come up over the top of a hill into the glory of a beautiful sunset with its gorgeous colors, then down into the little valley already purpling with mysterious twilight. So on, until, just at dark, we rode into our corral and a mighty tired, sleepy little girl was powerfully glad to get home. After I had mailed my other letter I was afraid that you would think me plumb bold about the little Bo-Peep, and was a heap sorrier than you can think. If you only knew the hardships these poor men endure. They go two together and sometimes it is months before they see another soul, and rarely ever a woman. I wouldn't act so free in town, but these men see people so seldom that they are awkward and embarrassed. I like to put them at ease, and it is to be done only by being kind of hail-fellow-well-met with them. So far not one has ever misunderstood me and I have been treated with every courtesy and kindness, so I am powerfully glad you understand. They really enjoy doing these little things like fixing our dinner, and if my poor company can add to any one's pleasure I am too glad. Sincerely yours, ELINORE RUPERT. Mr. Stewart is going to put up my house for me in pay for my extra work. I am ashamed of my long letters to you, but I am such a murderer of language that I have to use it all to tell anything. Please don't entirely forget me. Your letters mean so much to me and I will try to answer more promptly. Homework: Old West Acrostic • Describe your personal perspective on the unit theme question (Manifest Destiny or Destruction?). Decide if the closing of the West meant the fulfillment of our “Destiny” or the destruction of a legacy. • Use the word “Old West” to write 7 sentences on your perspective. The first letter for each sentence must begin with the letters listed below. • Include 3+ illustrations related to context, and 5+ colors. O L D W E S T Manifest Destiny or Destruction? Visual Discovery Unit Theme Question Did the closing of the American west fulfill Manifest Destiny or manifest destruction? Preview: Sweet Betsy From Pike Did you ever hear tell of Sweet Betsy from Pike, Who crossed the wide mountains (blue ridges) with her lover Ike, Two yoke of cattle, a large yeller dog, A tall Shanghai rooster, and a one-spotted hog. Singing too-ra-li-oo-ra-li-oo-ra-li-ay One evening quite early they camped on the Platte, Twas near by the road on a green shady flat. Betsy, sore-footed, lay down to repose-With wonder Ike gazed on that Pike County rose. Singing too-ra-li-oo-ra-li-oo-ra-li-ay Out on the prairie one bright, starry night, They broke out the whiskey, and Betsy got tight. She sang and she shouted and danced o'er the plain, And she showed her bare arse to the whole wagon train. Singing too-ra-li-oo-ra-li-oo-ra-li-ay A miner said, "Betsy, will you dance with me?" "I will that, old hoss, if you don't make too free. Don't dance me hard, do you want to know why? Doggone you, I'm chock-full of strong alkali." Singing too-ra-li-oo-ra-li-oo-ra-li-ay The Shanghai ran off, and the cattle all died, That morning the last piece of bacon was fried. "Dear old Pike County, I'll go back to you"-Says Betsy, "You'll go by yourself if you do!" Singing too-ra-li-oo-ra-li-oo-ra-li-ay The Injuns came down in a thundering horde, And Betsy was scared they would scalp her adored. So under the wagon-bed Betsy did crawl And she fought off the Injuns with musket and ball. Singing too-ra-li-oo-ra-li-oo-ra-li-ay They swam the wide rivers and crossed the tall peaks, And camped on the desert for weeks upon weeks. Starvation and cholera, hard work and slaughter-They reached California 'spite of hell and high water. Singing too-ra-li-oo-ra-li-oo-ra-li-ay Singing too-ra-li-oo-ra-li-oo-ra-li-ay Questions •What is the mood of the song’s melody? •Where was Sweet Betsy headed? •Why would Betsy, the pioneers, and others be willing to risk such hardships? •This song was written in the 1800’s as many people were making their journey out west. Why would a song like this have been written? •Why do you think this song survived to become a folk song today? Homework: Old West Acrostic • Describe your personal perspective on the unit theme question (Manifest Destiny or Destruction?). Decide if the closing of the West meant the fulfillment of our “Destiny” or the destruction of a legacy. • Use the word “Old West” to write 7 sentences on your perspective. The first letter for each sentence must begin with the letters listed below. • Include 3+ illustrations related to context, and 5+ colors. O L D W E S T