here - Collaborative Learning Project

advertisement

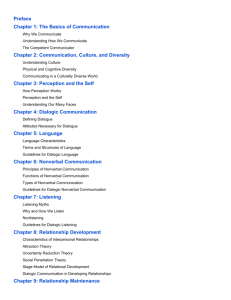

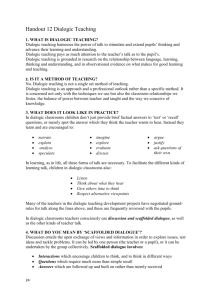

The case for a more oracybased primary curriculum John Smith Manchester Metropolitan University Institute of Education. j.smith@mmu.ac.uk NATE Conference April 5th 2009 The Structure of this Presentation 1. A (very) brief history of UK oracy initiatives in recent decades. 4. Feedback and discussion. 2. Arguments for change and the current situation. 3. Some alternatives: “dialogic teaching” and “Philosophy for Children”. Uneven development of “oracy” over many years in UK primary schools. Key points (some with rough dates) include: 1960s: Work of Barnes, Bernstein/Labov, Halliday, Chomsky and many others. 1970s: Joan Tough’s work for the Schools Council. 1975: The Bullock Report (“A Language for Life”) 1987-93: National Oracy Project. TALK ORACLE This decade: “Dialogic teaching” (eg Alexander, 2008.) Why should we encourage greater oracy in our primary classrooms? Literacy skills make up a vital aspect of children’s language resources but oral skills are vital too. We are likely to improve children’s literacy skills if we take a more holistic approach to their language development. We will encourage weak writers who are constantly reminded of their lack of skill in this area. We will move the UK primary classroom culture closer to more successful models seen elsewhere in the world. In doing so we will develop better thinking in groups (see for example Mercer’s Vygotskyan idea of the “IDZ”) and by individuals. Some encouraging signs. I asked teachers and trainee teachers about the balance between speaking and writing in their classrooms. I asked them to indicate on a line the balance they would like to have in their classroom between children speaking and children writing and I coded their responses 1 – 5 from “Entirely Speaking” (1) to “Entirely writing” (5) with 3 as the mid-point or exact balance between speaking and listening. The average trainee response (90 in total) was approx 2.43. The average teacher response (18 in total) was approx. 2.94 Both groups appeared to favour a greater weighting on oracy than literacy, the trainees even more strongly than the teachers. Various current initiatives to use/stimulate oracy eg “Talk(ing) partners” “Talking Maths” “Talk for writing” Moves towards “dialogic teaching” (more about this later) What is classroom talk like at present? Evidence has consistently shown that teachers dominate classroom talk. Children typically have few opportunities to talk and their contributions are often “low-level” in terms of intellectual demand. A very common pattern of classroom interaction has been described as I-R-F (first identified by Sinclair and Coulthard, 1975), which stands for: Initiation (Teacher) eg “What is the capital of France?” Response (Child) eg “Paris” Feedback (Teacher) eg “Good boy.” References in this slide and the next: Nystrand, M et al (1997) Opening dialogue: understanding the dynamics of language and learning in the English classroom. New York: Teachers’ College Press. Sinclair, J. McH. & Coulthard, R.M. (1975) Towards an analysis of discourse: the English used by teachers and pupils. London: Oxford University Press. Smith, F et al (2004) “Interactive whole class teaching in the National Literacy and Numeracy Strategies”, British Educational Research Journal 30 (3) From monologue to dialogue: looking more closely at “interactive” lessons The USA seems very similar to the UK. Nystrand and colleagues found that in many classrooms, talk was: “…overwhelmingly monologic. When teachers were not lecturing, students were either answering questions or completing seatwork. The teacher asked nearly all the questions, few questions were authentic, and few teachers followed up student responses.” (Nystrand et al, 1997, p 33) Further research suggests that this is a global problem. • A major piece of research into the “interactive whole class teaching” promoted by the Strategies over the last decade has found that: “In the whole class section of literacy and numeracy lessons, teachers spent the majority of their time either explaining or using highly structured question and answer sequences. Far from encouraging and extending pupil contributions to promote high levels of interaction and cognitive engagement, most of the questions asked were of a low cognitive level designed to funnel pupils ‘ response towards a required answer.” Smith et al (2004) p 408 Mercer and Dawes suggest that implicit rules exist to underpin this state of affairs: ‘Only a teacher can nominate who can speak.’ ‘Only a teacher may ask a question without seeking permission.’ ‘Only a teacher can evaluate a comment made by a participant.’ ‘Pupils should try to provide answers to teachers’ questions which are as relevant and brief as possible.’ ‘Pupils should not speak freely when a teacher asks a question, but should raise their hands and wait to be nominated.’ Mercer, N and Dawes, L: Chapter 4 ‘The value of exploratory talk’ in Mercer, N and Hodgkinson, S (eds) (2008) Exploring talk in school. Sage A movement is developing in this country which aims to establish a different type of teaching, one based on dialogue rather than monologue. It is known as “dialogic teaching”. Dialogic teaching can involve teaching the whole class or a group or just one child. Essential features of “dialogic teaching” (from Alexander, 2008). It is: One approach which demonstrates many of the features of “dialogic teaching” is “Philosophy for Children” (see eg Fisher, R. (2003) Teaching Thinking (2nd Edition), London: Continuum.). •Collective Community behaviours consistent with “Philosophy for Children” (selected from Lipman, M., 1991. Thinking in Education. New York: Cambridge University Press) •Reciprocal “Members question one another… •Supportive Members build on one another’s ideas •Cumulative Members deliberate among themselves •Purposeful Members cooperate in the development of rational problem-solving techniques” Mortimer and Scott suggest four classes of communicative approach Interactive Dialogic Nondialogic Non-interactive Interactive/dialogic Interactive/dialogic Non-interactive/dialogic Noninteractive/dialogic Interactive/authoritative Interactive/authoritative NonNoninteractive/authoritative interactive/authoritative From Mortimer, E F and Scott P H (2003) Meaning-making in science classrooms. Buckingham: Open University Press Can this kind of work be creative? Roy van den Brink-Budgen writes: “I must now try to define what I mean when I write of creativity in relation to critical thinking. I do not mean it in the strong sense of the production of ideas that have not been thought of before…I do not mean it in the even stronger sense of the production of historically important insights. The meaning of creativity I want to defend…follows the work of Margaret Boden who makes the distinction between historical and psychological creativity. Thus ideas can be H-creative (as in the example of Kepler’s thinking of elliptical orbits) and P-creative (in the sense that each of us might have an idea which we could not have thought of before). My contention is that critical thinking requires, encourages and develops creativity in the sense of Boden’s pyschological creativity.” (van den Brink-Budgen, 2002, p 31) From van den Brink-Budgen, R (2002) “The creativity of critical thinking” Teaching Thinking and Creativity, Spring 2002, pages 28-32 The Primary Reviews Recommendation 7: Primary schools must continue to give priority to literacy and numeracy, whilst making sure that serious attention is paid to developing spoken language intensively as an attribute in its own right and essential for the development of reading and writing. DCSF, 2004, The Independent Review of the Primary Curriculum: Interim Report (Available online at Teachernet Online Publications for Schools, p44). First, it is a recurrent theme of this Review that in England literacy is too narrowly conceived and that spoken language has yet to secure the place in primary education that its centrality to learning, culture and life requires, or that it enjoys in the curriculum of many other countries. The current national curriculum formulation, as ‘speaking and listening’, is conceptually weak and insufficiently demanding in practice, and we would urge instead that important initiatives like the National Oracy Project be revisited, along with more recent research on talk in learning and teaching, as part of the necessary process of defining oracy and giving it its proper place in the language curriculum. Alexander, R.J. (2009) Towards a New Primary Curriculum: a report from the Cambridge Primary Review. Part 2: The Future. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Faculty of Education (p 47)