Stop consonant voicing lecture notes

Stop Consonant Voicing

(and 2

nd

language learning)

The English phonemic inventory of stops includes 6 sounds:

/b/ /d/ /g/ (voiced, V+)

/p/ /t/ /k/ (unvoiced, V-)

Voiced: Vocal folds buzz

Unvoiced: Vocal folds don’t buzz

Should be simple to specify the articulatory and acoustic features that distinguish V+ from V. It isn’t. Why? (a) There are quite a few phonological rules that apply to voicing distinctions. (b) The details vary with context, especially initial vs. final stops. We’re going to stick with initial stops.

Main feature: Voice-onset time:

Articulatory definition: Interval between articulatory release and the onset of voicing; e.g., if the vocal folds start vibrating 20 ms following release, VOT=20 ms.

That’s it.

Acoustic definition: “Burst-to-buzz interval”

– interval between the burst of noise signaling articulatory release and the onset of periodic vibration. e.g., if periodic vibration follows the release burst by,

VOT=20 ms.

Two different ways of saying the same thing.

[bA] [pHA

]

VOT = ~0

Release

Release & voicing ~simultaneous

Voicing onset

VOT = ~115 ms

Voice Onset Time (VOT)

[p h A

]

[bA

]

VOT ~0 msec

VOT ~85 msec voicing onset release voicing onset and release ~ simultaneous

VOT = Interval between articulatory release and onset of voicing.

Voice Onset Time (VOT)

[p h A t]

[spA t]

VOT ~10 msec

VOT ~85 msec voicing onset release

Very short delay between release and voicing onset

(~10 ms)

[spAt] (unaspirated [p])

With [s] edited out

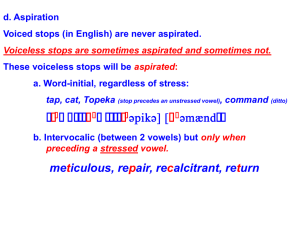

pack [p h Qk] capping [k h QpIN]

(aspirated [p])

(lightly aspirated [p])

/p/ precedes stressed vowel (aspirated)

/p/ precedes unstressed vowel (unaspirated or lightly aspirated)

One more wrinkle. English has two phonological (phonemic) voicing categories, but in VOT terms, there are three .

short lag release & voicing

~simultaneous lead long lag voicing precedes release longish delay betw. release & voicing

Another Example of Short-Lag, Lead (“prevoiced”), and Long-Lag (aspirated) VOTs

(For the long-lag [i.e., aspirated] stop, note that F

1 very weak during the aspiration interval. This is sometime called the “F

1

-cutback” cue.) is

10

phonologically voiced

(allophonic variants) of /d/ phonologically unvoiced short lag release & voicing

~simultaneous lead long lag voicing precedes release longish delay betw. release & voicing

phonologically voiced

(allophonic variants) of /d/ phonologically unvoiced short lag lead

In English, these two are in free variation long lag

Left-to-right:

The Spanish word peso as it might be mispronounced by a native English speaker (it’s aspirated; it shouldn’t be).

The Spanish word beso (kiss) as it might be spoken by a native Spanish speaker.

The Spanish word peso ) as it might be spoken by a native Spanish speaker.

13

What’s the Lesson Here?

Languages divide up the phonetic world in different ways. This is a very important idea.

English:

Phonol. V+ Phonol. V-

Lead Short-Lag Long-Lag

Español:

Phonol. V+ Phonol. V-

Lead Short-Lag

Where’s the long lag

(aspirated) stop? No got.

What, if anything, is the relevance of these differences in how the phonetic world is divvied up?

In 2 nd language learning it’s a very big deal .

Native English speakers need to: (1) attend to the difference between lead and short-lag (beso-peso) which they have spent years learning to ignore

(they’re in free variation in English) , and (2) learn to ditch the aspirated stop [pHeso] entirely.

Seems like this shouldn’t be that hard – English speakers already have all 3 phonetic types; they just need to learn to use them differently.

So, it seems as though the native English speaker’s task should be fairly straightforward.

Is it?

Without pretty explicit formal instruction (and sometimes with it) many English speakers never figure it out, even after decades of immersion.

It is not uncommon for native English speakers to spend many years living in Spanish-speaking countries without ever: (1) distinguishing lead from short-lag, or (2) abandoning aspirated

(long-lag) stops.

(Kids figure this stuff out almost immediately, though. That’s another [long, well documented, but poorly understood] story.)

What problem does the Spanish speaker face in learning English?

(1) Learn to ignore the now irrelevant lead/shortlag difference (once again, these are allophonic variants in English, not distinct phonemes).

(2) Develop the brand-new long-lag sound type.

How easy are these things? Not.

Many Spanish speakers spend very long periods of time immersed in English-speaking environments without ever abandoning their

Spanish voicing system: V+ = lead, V- = shortlag, no aspirated stops.

Cross-language variation in how phonetic categories are divided up does not end there.

Below are the 3 phonetic types we’ve been discussing: lead, short-lag, and long-lag. Thai is one of many languages for which all 3 categories are phonologically (phonemically) contrastive; i.e., Thai has 3 voicing categories, not 2.

How Thai divvies up the phonetic world:

Phon. Prevcd Phon. V+ Phon. V-

Lead Short-Lag Long-Lag

Just for yucks:

Hindi (& several other Indian languages):

Prevcd V+ VV+ aspirated

Lead Short-Lag Long-Lag Lead/Long Lag

Why am I bothering to tell you all this?

This VOT stuff is just one example

( part of one e.g. – initial stops only) of the kind of problem faced by:

1. Children learning their native language – they have to learn how to divide up the phonetic world; i.e., figure out what phonetic types are grouped together and which ones are contrastive (phonemically/phonologically distinctive).

2. Adults learning a 2 nd language : it’s the same problem – what distinctions matter linguistically (phonemically/phonologically) and which ones are allophonic.

Kids solve these problems (with their native tongue and with a new language) gracefully and with astonishing speed.

Adults don’t fare so well. Why?

As a general thing, the more you know about a thing

(speech/language in this case) the easier it is to learn new things in that same area. Speech & language don’t work this way – hard-won knowledge about L1 gets in the way of learning

L2. Once a native English speaker learns to ignore the difference between lead and short-lag stops, it’s extremely difficult to unlearn it. (This is not unique to language.)

VERY IMPORTANT: I pick the initial stop voicing example because there’s a single cue (VOT) that you allows you to see what’s going on.

Examples are everywhere.

One more quick one:

English has lots of vowels, partly because

English: (a) distinguishes tense and lax vowels

(/ i I , e E , u U /, and (b) English has vowel reduction (weak vowels -> [] ).

Spanish (and other Romance languages – Italian,

Portuguese, French, Romanian, …) have many fewer – no tense-lax distinction, no vowel reduction.

VERY IMPORTANT: I pick the initial stop voicing example because there’s a single cue (VOT) that you allows you to see what’s going on.

Examples are everywhere.

One more quick one:

English has lots of vowels, partly because

English: (a) distinguishes tense and lax vowels

(/ i I , e E , u U /, and (b) English has vowel reduction (weak vowels -> [] ).

Spanish (and other Romance languages – Italian,

Portuguese, French, Romanian, …) has many fewer vowels – no tense-lax distinctions, no vowel reduction.

Spanish vowels (yellow circles), English

(yellow circles plus the un-circled symbols – not shown for English is the all-important schwa ).

The Spanish speaker learning English has some problems to solve, right? The nature of the problem is simpler than you may be thinking. Let’s look at just one English word:

Spanish version:

[politikal]

Native-Eng. Version:

What explains the

(common but not universal) native Spanish speaker’s pronunciation of this word?

(1) Short-lag rather than aspirated stops

Spanish version:

[politikal]

(didn’t discuss this)

(2) No vowel reduction

(English speaker uses

[] ) (3) No lax vowels (English speaker uses [I] )

Native Eng. Version:

[pHlIRkHl]

In all of these examples, the same thing is going on: The speaker’s knowledge of their native language is interfering with their ability to learn the new language – it’s called inter-language

interference.

Do adults learning a 2 nd language end up solving these problems?

There is no single answer to this. Age of learning plays a huge role (though it is not the only factor that matters).

The most striking is that many speakers never end up solving many of these clashes between

L1 and L2.

Ok, we’ve looked at the pronunciation of just one

English word as it might be pronounced by a native speaker of just one language – Spanish.

Further, except for the flap, we examined just two features – initial stop voicing and vowel quality.

How much have we learned from this one example?

Answer: Plenty.

With more time we could have looked at many other examples, but the nature of most of these problems look the same.