LEGAL REGULATION OF ART IN THE C.I.S.

AND CROSS-BORDER REPRODUCTIVE CARE.

P-068

Konstantin N. Svitnev

Rosjurconsulting, Reproductive Law & Ethics Research Center, Moscow, Russia

Abstract

Cross-border reproductive care

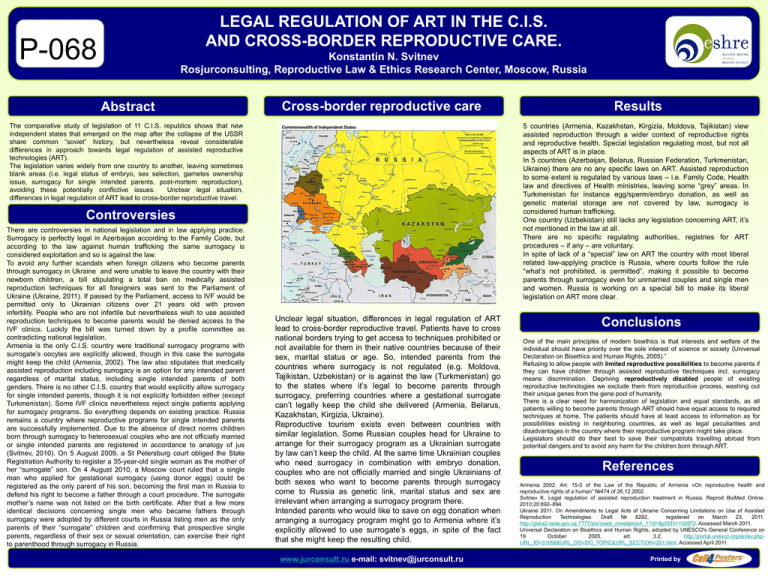

The comparative study of legislation of 11 C.I.S. republics shows that new

independent states that emerged on the map after the collapse of the USSR

share common “soviet” history, but nevertheless reveal considerable

differences in approach towards legal regulation of assisted reproductive

technologies (ART).

The legislation varies widely from one country to another, leaving sometimes

blank areas (i.e. legal status of embryo, sex selection, gametes ownership

issue, surrogacy for single intended parents, post-mortem reproduction),

avoiding these potentially conflictive issues.

Unclear legal situation,

differences in legal regulation of ART lead to cross-border reproductive travel.

5 countries (Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kirgizia, Moldova, Tajikistan) view

assisted reproduction through a wider context of reproductive rights

and reproductive health. Special legislation regulating most, but not all

aspects of ART is in place.

In 5 countries (Azerbaijan, Belarus, Russian Federation, Turkmenistan,

Ukraine) there are no any specific laws on ART. Assisted reproduction

to some extent is regulated by various laws – i.e. Family Code, Health

law and directives of Health ministries, leaving some “grey” areas. In

Turkmenistan for instance egg/sperm/embryo donation, as well as

genetic material storage are not covered by law, surrogacy is

considered human trafficking.

One country (Uzbekistan) still lacks any legislation concerning ART, it’s

not mentioned in the law at all.

There are no specific regulating authorities, registries for ART

procedures – if any – are voluntary.

In spite of lack of a “special” law on ART the country with most liberal

related law-applying practice is Russia, where courts follow the rule

“what’s not prohibited, is permitted”, making it possible to become

parents through surrogacy even for unmarried couples and single men

and women. Russia is working on a special bill to make its liberal

legislation on ART more clear.

Controversies

There are controversies in national legislation and in law applying practice.

Surrogacy is perfectly legal in Azerbaijan according to the Family Code, but

according to the law against human trafficking the same surrogacy is

considered exploitation and so is against the law.

To avoid any further scandals when foreign citizens who become parents

through surrogacy in Ukraine and were unable to leave the country with their

newborn children, a bill stipulating a total ban on medically assisted

reproduction techniques for all foreigners was sent to the Parliament of

Ukraine (Ukraine, 2011). If passed by the Parliament, access to IVF would be

permitted only to Ukrainian citizens over 21 years old with proven

infertility. People who are not infertile but nevertheless wish to use assisted

reproduction techniques to become parents would be denied access to the

IVF clinics. Luckily the bill was turned down by a profile committee as

contradicting national legislation.

Armenia is the only C.I.S. country were traditional surrogacy programs with

surrogate’s oocytes are explicitly allowed, though in this case the surrogate

might keep the child (Armenia, 2002). The law also stipulates that medically

assisted reproduction including surrogacy is an option for any intended parent

regardless of marital status, including single intended parents of both

genders. There is no other C.I.S. country that would explicitly allow surrogacy

for single intended parents, though it is not explicitly forbidden either (except

Turkmenistan). Some IVF clinics nevertheless reject single patients applying

for surrogacy programs. So everything depends on existing practice. Russia

remains a country where reproductive programs for single intended parents

are successfully implemented. Due to the absence of direct norms children

born through surrogacy to heterosexual couples who are not officially married

or single intended parents are registered in accordance to analogy of jus

(Svitnev, 2010). On 5 August 2009, a St Petersburg court obliged the State

Registration Authority to register a 35-year-old single woman as the mother of

her “surrogate” son. On 4 August 2010, a Moscow court ruled that a single

man who applied for gestational surrogacy (using donor eggs) could be

registered as the only parent of his son, becoming the first man in Russia to

defend his right to become a father through a court procedure. The surrogate

mother’s name was not listed on the birth certificate. After that a few more

identical decisions concerning single men who became fathers through

surrogacy were adopted by different courts in Russia listing men as the only

parents of their “surrogate” children and confirming that prospective single

parents, regardless of their sex or sexual orientation, can exercise their right

to parenthood through surrogacy in Russia.

Results

Unclear legal situation, differences in legal regulation of ART

lead to cross-border reproductive travel. Patients have to cross

national borders trying to get access to techniques prohibited or

not available for them in their native countries because of their

sex, marital status or age. So, intended parents from the

countries where surrogacy is not regulated (e.g. Moldova,

Tajikistan, Uzbekistan) or is against the law (Turkmenistan) go

to the states where it’s legal to become parents through

surrogacy, preferring countries where a gestational surrogate

can’t legally keep the child she delivered (Armenia, Belarus,

Kazakhstan, Kirgizia, Ukraine).

Reproductive tourism exists even between countries with

similar legislation. Some Russian couples head for Ukraine to

arrange for their surrogacy program as a Ukrainian surrogate

by law can’t keep the child. At the same time Ukrainian couples

who need surrogacy in combination with embryo donation,

couples who are not officially married and single Ukrainians of

both sexes who want to become parents through surrogacy

come to Russia as genetic link, marital status and sex are

irrelevant when arranging a surrogacy program there.

Intended parents who would like to save on egg donation when

arranging a surrogacy program might go to Armenia where it’s

explicitly allowed to use surrogate’s eggs, in spite of the fact

that she might keep the resulting child.

www.jurconsult.ru e-mail: svitnev@jurconsult.ru

Conclusions

One of the main principles of modern bioethics is that interests and welfare of the

individual should have priority over the sole interest of science or society (Universal

Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights, 2005).”

Refusing to allow people with limited reproductive possibilities to become parents if

they can have children through assisted reproductive ttechniques incl. surrogacy

means discrimination. Depriving reproductively disabled people of existing

reproductive technologies we exclude them from reproductive process, washing out

their unique genes from the gene pool of humanity.

There is a clear need for harmonization of legislation and equal standards, as all

patients willing to become parents through ART should have equal access to required

techniques at home. The patients should have at least access to information as for

possibilities existing in neighboring countries, as well as legal peculiarities and

disadvantages in the country where their reproductive program might take place.

Legislators should do their best to save their compatriots travelling abroad from

potential dangers and to avoid any harm for the children born through ART.

References

Armenia 2002. Art. 15-5 of the Law of the Republic of Armenia «On reproductive health and

reproductive rights of a human” №474 of 26.12.2002

Svitnev K. Legal regulation of assisted reproduction treatment in Russia. Reprod BioMed Online.

2010;20:892–894.

Ukraine 2011. On Amendments to Legal Acts of Ukraine Concerning Limitations on Use of Assisted

Reproduction

Technologies.

Draft

№

8282,

registered

on

March

23,

2011.

http://gska2.rada.gov.ua:7777/pls/zweb_n/webproc4_1?id=&pf3511=39973. Accessed March 2011.

Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights, adopted by UNESCO's General Conference on

19

October

2005,

art.

3.2.

http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.phpURL_ID=31058&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. Accessed April 2011.

Printed by