Combination HIV Prevention:

Crafting a New Standard for the

Long-term Response to HIV

Carlos F. Cáceres, Cayetano Heredia University/IESSDEH, Peru

Barbara de Zalduondo, UNAIDS, Switzerland

Timothy Hallett, Imperial College London, UK

Carlos Avila, UNAIDS, Switzerland

Michaela Clayton, AIDS Rights Alliance for Southern Africa, Namibia

“A sensible way to go…”

• “Combination Prevention”

highlighted in discussions in 2008

Conference

– See The Lancet Series 2008

• Increasingly regarded as the

‘sensible’ way to go

– 2008 Global Prevention Working

Group,

– 2009 UNAIDS Outcome Framework;

– 2009 Implementers Meeting;

– Global Fund Board 2009

recommendation;

– UNAIDS Prevention Reference

Group (PRG), 2009; etc

…but not a guiding principle yet!

• Yet still not a guiding principle applied systematically

in HIV programming

• Some doubts remain – is it anything new? Is it

necessary?

• Our goal today:

– Clarify concepts around Combination

Prevention

– Argue that structural interventions, including

human rights strategies, are core business of

HIV prevention

– Discuss how and why it can provide a

standard for a longer-term response to HIV.

What is Wrong with Prevention Now

Risk Groups

Risk

Practices

Vulnerability

Cultural

context

What is Wrong with Prevention Now

Most-at-risk

populations

Vulnerability

Individual

Cultural

context

Risk

Practices

…what is wrong? (2)

• Inconsistent application of

standards

– “Know Your Epidemic and

Response;” Know and engage

with key audiences; allocate

resources to suit Modes of

Transmission, etc.

– Lack of consensus on

approaches

• Fragmentation and

scatter

(see Bertozzi et al, The Lancet, 2008)

…what is wrong? (3)

• Focus on short-term results

– Research and programme evaluations with 6-36 month

follow-up

– Low-hanging fruit - preference for solving bite-sized

problems, neglecting the underlying causes of risk and

vulnerability (aids2031 Social Drivers Workgroup)

• Limited evaluation and cumulation of learning from

country programmes

– Limited investment in prevention evaluation research

– Confused language describing prevention aims and actions:

goal, activity, audience, setting, proximity of effect

Percent Spending in Programs focusing on Most-at-risk

Populations

(as a Percentage of Total Prevention Spending)

8.00%

7%

7.00%

6.00%

5.00%

Harm reduction programs for IDUs

Programs for MSM

Programs for sex workers and their clients

4.00%

3.00%

2.00%

1.00%

0.00%

Low level

Concentrated

Generalized

Source: UNAIDS HIV Expenditure Studies

Individuals

National/

Societal

Group/ Community/

Organizations

(women, girls,

children, men,

boys, transgender)

Relationships

Family/Partner

Individuals

(women, girls,

children, men,

boys, transgender)

What is Combination Prevention?

• Recapitulating: Analogy to combination treatment

Cited by Coates et al., 2008

Combining what?

• Type 1 – Common tactic combining two or more

intervention strategies

– E.g.. IDU: Needle & syringe programs + opiate substitution.

– E.g. US NIH “MP3” (methods for prevention packages program)

• Type 2 - Combining diverse strategies to fit the needs of

diverse sub-groups in the population

– E.g. strategies for MSM, trans, IDU, FSW, PMTCT, discordant couples

• Type 3 – Strategic combinations of biomedical, behavioral

and structural approaches to address key causes of HIV

risk and vulnerability for a particular population

– E.g. Synergistic interventions for interrelated sub-groups

– E.g. MSM: BCC, STI Tx, decriminalization, mobilization

– E.g. IDU: NSP, OSP, decriminalization, mobilization

UNAIDS Prevention Reference

Group Definition

• “The strategic, simultaneous use of different

classes of prevention activities (biomedical,

behavioral, social/ structural) that operate on

multiple levels (individual, relationship,

community, societal), to respond to the specific

needs of particular audiences and modes of HIV

transmission, and to make efficient use of

resources through prioritizing, partnership and

engagement of affected communities”

What Kind of Evidence is Needed?

Human Rights

Epidemiological

• e.g. Data from Modes

patterns and trends

of Transmission

Studies

Main drivers of

those epidemic

trends

Effective

Interventions to

address epidemic

patterns and their

drivers

• e.g. Specific forms of

social exclusion (class,

gender, sexuality) and

their confluence

• e.g. Effective

behavioral, biomedical,

structural interventions

Case et al., AIDS International Conference, 2010

Potential Effects Bringing Proven

Prevention Programmes to Scale

Status Quo

25M infections could be averted!

Scaled

Intervention

In GE: Circumcision, HTC, Treatment, Community Mobilization

In CE: Increase condom use and harm reductiong in MARPS

Biomedical, Behavioral, Structural

• Behavioral prevention

– Traditional prevention work: Behavioral change (from 11 to groups to behavioral change communication)

– Change individuals’ practices to reduce exposure and

infectivity

• Reduction of partners, condom use, use clean IDU equipment

• Biomedical prevention

–

–

–

–

Male circumcision

ARV prophylaxis (PMTCT. PEP)

Antiretroviral Treatment (ART)

Experimental: PrEP; ART-based microbicides,

vaccines

Structural Interventions

• Many definitions, many conceptual frameworks

– e.g collections in collections in AIDS 1995; AIDS, 2000; aids2031

Social Drivers Working Group.

• Focused on aspects of environment that increase people’s

vulnerability to HIV infection or decrease access.

• Body of work on Social Determinants of Health.

• Main types (from Robin Vincent, 2009):

– Changes in laws and regulations,

– Promoting changes in culture and social norms (e.g.

gender inequalities, HIV related stigma),

– Environmental enablers (e.g. increasing access),

– Community mobilization and empowerment,

– Policy dialogue and prevention diplomacy

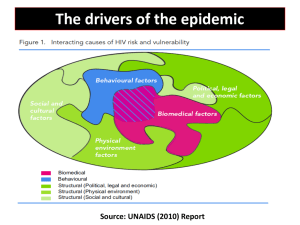

Interacting causes of HIV risk and vulnerability

Behavioural factors

Social and cultural

factors.

Biomedical

Political and

economic factors

SYNTHESIS

Gap Analysis

Biomedical factors

Physical environment

factors

17

Biomedical

Behavioural

Structural (Social and cultural, Political and economic; Physical)

Combination Prevention

Behavioural intervention

strategies:

Social and cultural

intervention strategies:

Behaviour change communication

School based HIV education;

•Community dialog and

mobilization

Peer-led advocacy and persuasion

•Advocacy and coalition building

for social justice

Influence cost of access to serviceds

Couseling

•Media and interpersonnal

communication to clarify values,

change harmful social norms;

Biomedical

•Education curriculum reform,

expansion and quality control

•Etc.

Political and

economic intervention

strategies:

•Human rights programming;

Intervention strategies

addressing physical

environment:

•Housing policy and standards

•Access to land; subsistence;

•Infracstructure development –

transportation,

communications, etc.

•Prevention diplomacy with leaders at

all levels;

•Community Microfinance/microcredit

Etc.

SYNTHESIS

•Training/advocacy with police,

judges;

GapBiomedical

Analysis intervention

•Engaging leaders

strategies:

•Stakeholder analysis & alliance

•Improved STI services; Appropriate &

building;

accessible clinical services; condoms

•Strategic advocacy;

•Opiod substitution therapy, detox;

•Regulation/deregulation;

•Male circumcision

•Etc.

•PMTCT services – ARV prophylaxis

(PEP, PrEP, Microbicides)

•ART for prevention

•Etc.

;

18

;

Biomedical

Behavioural

Structural (Social and cultural, Political and economic; Physical)

Human Rights: Beyond Rhetoric

• Ethical Principle: CP is a strategy to reach

Universal Access (Human Rights [HR]-based)

• Technical reason: Sound consideration of HR is a

necessary element of successful programs

– Lack of HR perspective may lead to program failure

• Condom use programming in Asia designed without

considering sex workers’ HR issues led to abuses and failure.

– Also need to face legal & HR-related structural barriers

– Good prevention planning starts with a HR analysis

– Insufficient to just ‘protect HR’ at implementation

• Testing promotion programs: Understand people’s needs + rights and

then design the best interventions within that framework.

– Environments protective of people’s rights unleash

community and individual motivation to avoid HIV

Ukraine: Reducing Police Violence

HIV Infections Averted By Structural Changes

1000

4 - 19%

800

600

3 - 9%

400

2 - 5%

200

0

662

343

209

Est for Odessa

Est for Makeevka

Est for Kiev

Elimination of police beatings

Strathdee, Hallett, Bobrova et al., Lancet 2010

Stigma Reduction can improve

PMTCT Outcomes

Per 100,000 women (assuming 15% prevalence at ANC)

Watts, Zimmerman, Eckhaus and Nyblade, 2010. Modelling the Impact of

Stigma on HIV and AIDS Programmes: Preliminary Projections for

Mother-to-Child Transmission. ICRW and LSHTM Working Paper.

Myths about Combination Prevention

Combination prevention

is “doing everything for

everyone”

It can’t be done

No! – that’s poorly

designed prevention!

Not so – IMAGE, Avahan, Stepping

Stones, Sonagachi

Need political courage to focus where the

need is

Need capacity to deliver to scale

HIV Prevalence Among Sex workers in Mysore

DATA

Fit with AVAHAN

intervention

removed

Estimated Impact

of intervention

“Best fit” projection

Source: Pickles, Foss, Vickerman et al., 2010

Beyrer et al, working paper

Peru: Political Courage and Community Mobilization

is Needed to Change the Epidemic’s Trajectory

Present level

100% MSM coverage

Null

Current

100% MSM interventions

Myths about Combination Prevention

It can’t be evaluated

True that it’s difficult to map and prove the

causal chain.

Easier to show effects at similar level of

proximity.

Need to better assess effects of programs that

include structural interventions.

Need Combination Evaluation!

True that measuring impact of any intervention

is difficult.

No reliable, validated, working test for HIV

incidence to compare combinations.

But – analysis of HIV prevalence can allow a

retrospective estimate of changes in incidence

in relation to programme and context.

Zimbabwe: Use of Modelling to

Assess Impact over Time

10

10

Natural decline in

incidence ~ 1990

HIVincidence

incidence(per

(per100pyar)

100pyar)

HIV

8

8

Accelerated

decline in

incidence, due

to behaviour

change: ~ 2000

6

6

4

4

2

2

0

0

1980

1980

1985

1985

1990

1990

1995

1995

Year

Year

2000

2000

Hallett, Gregson, Gonese, et al., Epidemics, 2009

2005

2005

2010

2010

Myths about Combination Prevention

It’s too expensive

Compared to what?

The missing pieces are often the structural

interventions. Contrary to common perception,

the additive costs can be quite reasonable.

Synergies.

Economies of scale

Human rights (HR) services are 1.4 % of

ART programme costs in South Africa

Source: Jones et al: Human Rights Costing of HIV for

Prevention in a Southern African Setting. Poster at aids2010.

• Charlotte watts/ICRW slide (

Watts, Zimmerman, Eckhaus and Nyblade, 2010. Modelling the Impact of

Stigma on HIV and AIDS Programmes: Preliminary Projections for Motherto-Child Transmission. ICRW and LSHTM Working Paper.

http://seofrecencaricias.blogspot.com

Structural Interventions “float all boats”

Gender

Equity

effects

Sexual

Inclusion

Effects

Poverty

Reduction

Effects

HIV

effects

Social Change Takes Time – START NOW!

Results in 1-2

years

Results in 3-5

years

Results in > 5

years

e.g. Knowledge of HIV

prevention, Awareness

of risks of Multiple

concurrent partners,

supportive professional

and workplace policies

e.g. Supportive

community

attitudes,

Enforcement of

supportive

policies

Programmes have focused on those, shortterm results for 25 years!

UNAIDS Social Change Communication Working Group, 2008.

More

Equitable

Gender

Norms

Positive Health, Dignity and Prevention

"Positive health, prevention and dignity highlights the

importance of placing the person living with HIV at the

centre of managing their health and well-being, within the

sociocultural and legal context in which they live. It also

stresses the importance of addressing prevention and

treatment simultaneously and holistically and emphasizes

the leadership of people living with HIV in responding to

policy and legal barriers and in driving the agenda

forward.“

Kevin Moody, Director and CEO, GNP+

Challenges

• Need better tools to ‘know our epidemics’

– Ascertaining incidence, size estimations

– Standardizing terminology

• Need more evidence about our responses

– Insufficient data on what works, contradictions,

how to improve conceptualization of CP

– What combinations are necessary and sufficient

in specific settings? Coverage, intensity?

Take-Home Messages

• Focus on individuals for prevention (w/biomedical

and behavioral approaches) is not sufficient

• CP is not about implementing rigid panel of

redundant/irrelevant interventions.

• Rather, CP is strategic, evidence-informed,

combination of biomedical, behavioral and

structural strategies in a HR framework.

• Investing in structural interventions is not only an

ethical obligation – it is a worthwhile investment

• Needed for a sustained, long-term response

• A flagship of a “prevention revolution”!

“The successful implementation of HIV interventions

therefore demands, first of all, that local-level barriers be

addressed and that an ‘enabling environment’ be created.

This is not difficult to achieve.

Often, what appears to be intractable resistance to

respecting the basic rights of most-at-risk groups yields to

thoughtful advocacy and bridgebuilding with local

authorities and powerbrokers.”

Commission on AIDS in Asia. 2008. Redefining AIDS in Asia: Crafting an Effective

Response. Report of the Commission on AIDS in Asia, . New Delhi, India: Oxford

University Press

Acknowledgements

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

B. Zalduondo, T. Hallett, C. Avila, M. Clayton

K. Daly (ICASO), K. Thomson (UNAIDS)

All authors who shared their work with us

C. Beyrer et al. (JHUSPH/WB)

Auerbach et al, 2009 (aids2031)

Social Drivers Workgroup, aids2031

Sam McPherson (International HIV Alliance)

UNAIDS Prevention Reference Group

WHO HIV Department

IESSDEH and USSDH/Cayetano Heredia University

Thanks!