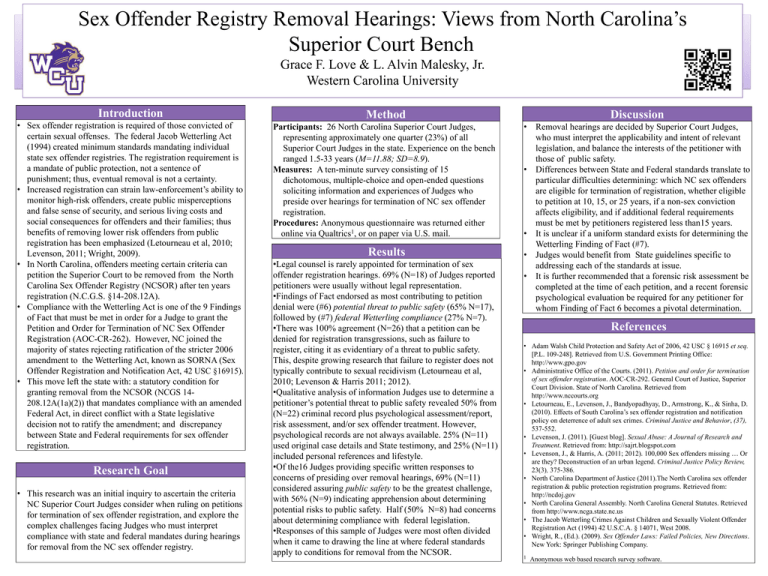

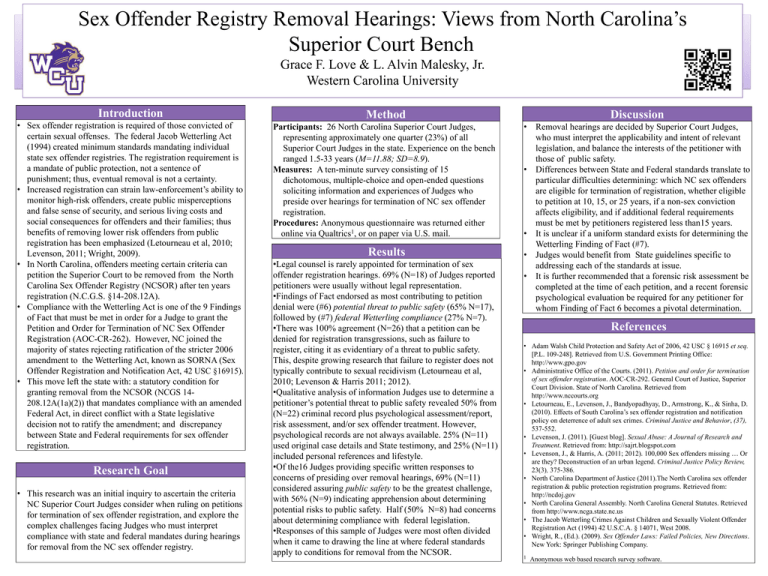

Sex Offender Registry Removal Hearings: Views from North Carolina’s

Superior Court Bench

Grace F. Love & L. Alvin Malesky, Jr.

Western Carolina University

Introduction

• Sex offender registration is required of those convicted of

certain sexual offenses. The federal Jacob Wetterling Act

(1994) created minimum standards mandating individual

state sex offender registries. The registration requirement is

a mandate of public protection, not a sentence of

punishment; thus, eventual removal is not a certainty.

• Increased registration can strain law-enforcement’s ability to

monitor high-risk offenders, create public misperceptions

and false sense of security, and serious living costs and

social consequences for offenders and their families; thus

benefits of removing lower risk offenders from public

registration has been emphasized (Letourneau et al, 2010;

Levenson, 2011; Wright, 2009).

• In North Carolina, offenders meeting certain criteria can

petition the Superior Court to be removed from the North

Carolina Sex Offender Registry (NCSOR) after ten years

registration (N.C.G.S. §14-208.12A).

• Compliance with the Wetterling Act is one of the 9 Findings

of Fact that must be met in order for a Judge to grant the

Petition and Order for Termination of NC Sex Offender

Registration (AOC-CR-262). However, NC joined the

majority of states rejecting ratification of the stricter 2006

amendment to the Wetterling Act, known as SORNA (Sex

Offender Registration and Notification Act, 42 USC §16915).

• This move left the state with: a statutory condition for

granting removal from the NCSOR (NCGS 14208.12A(1a)(2)) that mandates compliance with an amended

Federal Act, in direct conflict with a State legislative

decision not to ratify the amendment; and discrepancy

between State and Federal requirements for sex offender

registration.

Research Goal

• This research was an initial inquiry to ascertain the criteria

NC Superior Court Judges consider when ruling on petitions

for termination of sex offender registration, and explore the

complex challenges facing Judges who must interpret

compliance with state and federal mandates during hearings

for removal from the NC sex offender registry.

Method

Discussion

Participants: 26 North Carolina Superior Court Judges,

representing approximately one quarter (23%) of all

Superior Court Judges in the state. Experience on the bench

ranged 1.5-33 years (M=11.88; SD=8.9).

Measures: A ten-minute survey consisting of 15

dichotomous, multiple-choice and open-ended questions

soliciting information and experiences of Judges who

preside over hearings for termination of NC sex offender

registration.

Procedures: Anonymous questionnaire was returned either

online via Qualtrics1, or on paper via U.S. mail.

•

Results

•

•Legal counsel is rarely appointed for termination of sex

offender registration hearings. 69% (N=18) of Judges reported

petitioners were usually without legal representation.

•Findings of Fact endorsed as most contributing to petition

denial were (#6) potential threat to public safety (65% N=17),

followed by (#7) federal Wetterling compliance (27% N=7).

•There was 100% agreement (N=26) that a petition can be

denied for registration transgressions, such as failure to

register, citing it as evidentiary of a threat to public safety.

This, despite growing research that failure to register does not

typically contribute to sexual recidivism (Letourneau et al,

2010; Levenson & Harris 2011; 2012).

•Qualitative analysis of information Judges use to determine a

petitioner’s potential threat to public safety revealed 50% from

(N=22) criminal record plus psychological assessment/report,

risk assessment, and/or sex offender treatment. However,

psychological records are not always available. 25% (N=11)

used original case details and State testimony, and 25% (N=11)

included personal references and lifestyle.

•Of the16 Judges providing specific written responses to

concerns of presiding over removal hearings, 69% (N=11)

considered assuring public safety to be the greatest challenge,

with 56% (N=9) indicating apprehension about determining

potential risks to public safety. Half (50% N=8) had concerns

about determining compliance with federal legislation.

•Responses of this sample of Judges were most often divided

when it came to drawing the line at where federal standards

apply to conditions for removal from the NCSOR.

•

•

•

Removal hearings are decided by Superior Court Judges,

who must interpret the applicability and intent of relevant

legislation, and balance the interests of the petitioner with

those of public safety.

Differences between State and Federal standards translate to

particular difficulties determining: which NC sex offenders

are eligible for termination of registration, whether eligible

to petition at 10, 15, or 25 years, if a non-sex conviction

affects eligibility, and if additional federal requirements

must be met by petitioners registered less than15 years.

It is unclear if a uniform standard exists for determining the

Wetterling Finding of Fact (#7).

Judges would benefit from State guidelines specific to

addressing each of the standards at issue.

It is further recommended that a forensic risk assessment be

completed at the time of each petition, and a recent forensic

psychological evaluation be required for any petitioner for

whom Finding of Fact 6 becomes a pivotal determination.

References

• Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006, 42 USC § 16915 et seq.

[P.L. 109-248]. Retrieved from U.S. Government Printing Office:

http://www.gpo.gov

• Administrative Office of the Courts. (2011). Petition and order for termination

of sex offender registration. AOC-CR-292. General Court of Justice, Superior

Court Division. State of North Carolina. Retrieved from

http://www.nccourts.org

• Letourneau, E., Levenson, J., Bandyopadhyay, D., Armstrong, K., & Sinha, D.

(2010). Effects of South Carolina’s sex offender registration and notification

policy on deterrence of adult sex crimes. Criminal Justice and Behavior, (37),

537-552.

• Levenson, J. (2011). [Guest blog]. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and

Treatment. Retrieved from: http://sajrt.blogspot.com

• Levenson, J., & Harris, A. (2011; 2012). 100,000 Sex offenders missing … Or

are they? Deconstruction of an urban legend. Criminal Justice Policy Review,

23(3), 375-386.

• North Carolina Department of Justice (2011).The North Carolina sex offender

registration & public protection registration programs. Retrieved from:

http://ncdoj.gov

• North Carolina General Assembly. North Carolina General Statutes. Retrieved

from http://www.ncga.state.nc.us

• The Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender

Registration Act (1994) 42 U.S.C.A. § 14071, West 2008.

• Wright, R., (Ed.). (2009). Sex Offender Laws: Failed Policies, New Directions.

New York: Springer Publishing Company.

1

Anonymous web based research survey software.