BirthofPoMoVenturi

advertisement

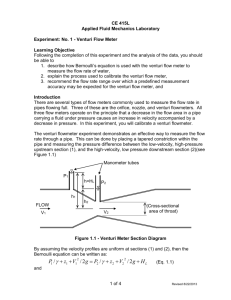

The Critique of the Modernist Project The Birth of Post-Modernism Chestnut Hill, Vanna Venturi House, 1963, Robert Venturi L. Mies van der Rohe: “Less is more.” Robert Venturi: “Less is a bore.” Post-Modernism introduced a challenge to an architecture or a design culture of minimalism and abstraction, an architecture dominated by the taste of its architects. Venturi argued that great architecture is not characterized by unity and simplicity. In his book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, first published by the Museum of Modern Art in 1966, Venturi made a case for creating architecture that has the same characteristics as great poetry in which words and phrases often have multiple meanings, layers of interpretation, and irony as enriching factors. Referring to the literary criticism of T. S. Eliot, Venturi argued that great architecture should be “complex and contradictory.” Philadelphia, Guild House, 1961-3, Robert Venturi Guild House introduced the notion that the taste of the client is more important than the taste of the architect. Especially in this kind of urban context, new buildings should not threaten older buildings; nor should they make the belongings of the inhabitants seem out of place. In other words, context is as important as content or intention. The concept of context began to have an impact on many architects. While Venturi considered the design of Guild House in the context of its urban setting and the lives of its intended occupants, other architects began to consider such things as history, vernacular tradition, and an inherited sense of place as contextual. Context offered a matrix for creating complex, contradictory, layered, and multi-valent architecture. Charles Moore, Searanch Condominiums, Sonoma County, California, 1964-66 Charles Moore, Faculty Club, University of California, Santa Barbara, 1968 Michael Graves, Benecerraf House addition, Princeton, NJ, 1969 First trained as a painter, Michael Graves never left his interest in color behind. While the Benecerraf addition employed an abstract white structural frame, it also introduced color and playful shapes as contrasting elements against the white frame. More important, Graves soon developed an interest in the idea of reintroducing classical elements into his work. These appeared in a number of smaller designs, especially for the Sunar showrooms in Chicago and Houston in the 1970s. Hardly defensible on the basis of physical context, Graves simply argued that these elements had inherent value as architectural elements expressing entry or portal, passage, protection or covering, order, and structure. Michael Graves, Sunar Showroom, Chicago, 1970s “House for an academical couple” by Robert A. M. Stern, 1974-76