A Brief History of Business

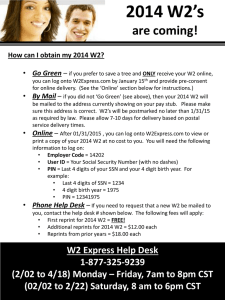

advertisement

A Brief History of Business Most histories of business start with the premise that business began with the advent of money and the end of the barter system. Many ancient civilizations therefore had a primitive business model with goods and services being sold for what we would call cash. Trade among various cultures was also a feature of the ancient world, dating back as far as the third millennium B.C. in Egypt. The Phoenecians, Greeks, and Carthaginians all created wealthy and powerful trading states during the first millennium B.C.; the Roman Empire built much of its dominance of the Mediterranean world on its continuous contact with other cultures and used its armies to help enforce good trading terms with client states. With the decline of the empire in the fifth and sixth centuries, barter returned throughout much of Europe until the 12th and 13th centuries, when the city-states of Italy (Venice and Genoa among others) brought about a tremendous resurgence of trade on the Mediterranean. By the time the great age of exploration arrived in the late 15th century, the business of foreign trade, whether founded by monarchies or pools of investors, had been well established. The seven northern provinces that formed the Dutch Republic were flexible enough to respond to these international market conditions; by the middle of the 17th century, the Dutch were the supreme economic power, and Amsterdam was the world’s leading financial and commercial center. This balance of power shifted by the beginning of the 18th century, when Britain led the world into an industrial revolution; this is the point when the history of modern business can be truly said to have begun. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business The Industrial Revolution In the late 17th and 18th centuries, economic power grew fastest in Great Britain. It arose from a proliferation of inventions, the availability of capital, a relatively fluid social order, a rising and mobile population, a responsive legal system, a government with power divided between the king and parliament, and an entrepreneurial spirit that was shared by all of the social classes. These factors – collectively called the Industrial Revolution – produced a profound change in the nature of commerce and business. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business Inventions Beginning in the 18th century, the pace of invention began to quicken as industrialization created unprecedented opportunities for wealth – and a powerful incentive for invention. The invention of the process of invention during the period of industrialization has been called the most important invention of all. One of the inventions that drove the Industrial Revolution was the steam engine. Before the 17th century, there were essentially four means of applying power to do work: humans (pushing, lifting, carrying, animals (pulling plows, transporting people, wind (powering sailing ships and windmills), and water (turning water wheels). The steam engine changed all this, providing a reliable source of power that could be used in many of the new industries that were being developed at the time. The first commercially successful steam engine was developed by Thomas Newcomen (1663-1729) and first used in 1712. Newcomen’s primitive engine was improved upon by James Watt (1736-1819), who produced a more efficient engine using rotary mechanics. Thanks to Watt’s steam engine, factories were liberated from water wheels and built closer to their sources of supply; ships could move in all directions, no longer dependent on the directions of the wind or the currents. The steam engine also made possible critical new mode of transportation – the railroad. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business Transportation The invention of the steam engine also made possible steam-powered ships that could travel to their destination more directly than sailing ships, reducing the time and costs of voyages. Now goods that moved along the railroads to port cities moved overseas on steamships, creating a vast flow of commerce between trading nations. One of the reasons that Britain’s industrialization moved at the pace it did was the availability of cheap transportation. From the 17th to the 19th centuries, Parliament passed a number of acts that facilitated the construction of roads, canals, and railroads. In 1829, George Stephenson (1781-1848) and his son Robert (1803-1859) successfully demonstrated a steam locomotive that traveled on iron rails. In 1830 it was adopted by the Liverpool and Manchester Railway and immediately put Britain ahead of the rest of the world in a form of transportation that was even cheaper than shipping by canals. Thereafter no country that aspired to industrialization could succeed without a network of railroads to carry the goods. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business The Factory System The first important industry to undergo profound changes during the Industrial Revolution was the textile industry, which was transformed by a series of inventions. Prior to 1700, most of the processes used to turn raw cotton or wool into fabrics were performed by hand, often by people working at home. During the 18th century, machines replaced human beings in all of the essential processes. This caused the cost of production to drop over time; merchants were able to sell fabric at lower prices, thus finding a mass market for their products. The change from small groups of widely dispersed workers to mechanized processes performed under one roof signaled the birth of the modern factory. Factories provided employment to hundreds of thousands of workers who otherwise would have found no employment or means of survival, although conditions in the factories and settlements where the workers lived were often deplorable. And although Britain had a social system based on class, it did not prevent entrepreneurs of the lower classes from rising to become factory supervisors, managers and owners. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business Industrialization Spreads to Europe As Britain was expanding under industrialization, it not only traded with European countries but also was a party – somewhat reluctantly – to transfer of technologies and ideas to the continent. European countries paid British engineers to help them establish new industrial enterprises; they hired British workers to come to work for them and – as they imported the goods of British industry – they learned how the goods were manufactured. They even were the beneficiaries of British investment in some of their enterprises. Investors thus had an incentive to transfer ideas and technologies to receptive European countries. The more forward-looking of the continental countries made full use of these advantages. For example, Germany - rich in resources, especially coal – was aggressive in developing its iron production capability. Germany ultimately excelled in industries that were fostered by its many fine universities. It came to dominate the field of chemistry and made important advances in the production and applications of electricity. French engineers developed sophisticated weaving machines, notably the Jacquard loom, named for its developer, J. M. Jacquard (1752-1834) The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business Industrialization in the United States In 1800 the United States was a new nation struggling to define itself; by 1900 it had the largest economy in the world and was the world’s leading industrial nation. America’s extraordinary economic growth during the 19th century is probably the most important business story in history. The country, even before westward expansion, was vast in comparison with its population. There was abundant fertile land on which to grow food and other useful crops such as cotton. Natural resources were also abundant, in the form of wood, coal, iron and copper ores, and oil. But America’s greatest resource was its people. A high birth rate provided most, but not all, of the rapidly growing population. Added to this were waves of immigrants who were ambitious, energetic, skilled, and entrepreneurial, eager to put their talents to work in the opportunities that the new country afforded. The first United States census in 1790 enumerated fewer than 4 million inhabitants; by 1870, there were almost 40 million inhabitants. This rapidly growing population not only supplied labor to industry but was also a growing pool of customers for the products of that industry. But even with this rapid population growth, there was a constant shortage of workers; agriculture and industry simply grew faster than the population. The country’s chronic labor shortage had two important effects on the growth of business and commerce. The first was that wages rose, attracting both native workers and ambitious and talented immigrants. The other was that agriculture and industry compensated for scarce workers by adopting and developing new technologies to increase productivity. By 1830, a surprisingly early date, productivity in the U.S. exceeded that of Great Britain. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) Transportation Constructing roads, canals, and railroads to connect the vast expanses of the North American continent required vast amounts of capital. The federal government did not have the financial resources to pay for transportation projects as public works, so it was up to the states and the private sector, including investors from abroad, to find most of the money. This created opportunities for visionaries to build the arteries of commerce – and, at the same time, create great wealth for themselves. Canals During the 18th century and the early 19th , water transportation was less expensive than land transportation, especially after the introduction of steam power. The existing rivers were soon supplemented and connected by systems of canals. The longest of these canals, and the one that inspired a wave of imitators, was the Erie Canal. The governor of New York state, DeWitt Clinton (1769-1828), understood the potential of connecting the Eastern seaboard with what was then the interior of the country. He pushed through the state legislature an authorization for $7 million to build a canal from Albany on the upper Hudson River to Buffalo on Lake Erie – a distance of 363 miles. It was one of the great engineering and construction projects of the century. After overcoming many obstacles, the canal opened in 1825 to great success. Soon many states and localities had built their own canals and created a web of water transportation. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) Railroads America’s canals were soon displaced by an even more economical means of transportation – the railroad. The building of the nation’s railroad system required enormous amounts of capital. Fortunes were made by entrepreneurs who could combine building with financing – although it was sometimes difficult to distinguish between the builders and scoundrels. The first great railroad entrepreneur was Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877). He began to invest in the stock of eastern railroad companies in the 1840’s; by the time of his death he controlled railroads that stretched from New York City to Chicago. The watershed achievement of railroad building in the 19th century was the completion of the first transcontinental railroad. As the nation expanded westward it clearly needed a rail connection to California. In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act that authorized the Union Pacific to build west from Omaha and the Central Pacific to build east from Sacramento until they met at a still undetermined location. On May 10, 1869, the two lines celebrated their linking-up in Promontory Point, Utah, northwest of Salt Lake City. Following that first meeting of the tracks at Promontory Point, several other transcontinental lines were laid, as well as many other trunk and feeder lines. As early as 1840 the total mileage of American railroads was 4,510 – exceeding the total mileage of Britain and continental Europe combined. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) Inventors Inventions and innovations had been essential to industrialization in Britain and Europe – and it was the same in the United States. Textiles American manufacturers were eager to learn about advances in technologies in their industries, and offered bounties, high pay and advancement as inducements to ambitious Europeans willing to emigrate. One of the most influential of these immigrant inventors was Samuel Slater (1768-1835), who had apprenticed in Britain with Jedediah Strutt (1726-1797), developers of the first water-powered spinning machine. In 1789, Slater immigrated to the United States, where he engaged in a series of ventures to build water-driven spinning machines. He continued to develop textile manufacturing technology and was a major innovator in the development of the American factory system. Steamships A number of inventors contributed to the development of a reliable steam-powered shipping industry. The most important was Robert Fulton (1765-1815); in August 1807 his boat, the Clermont, made a test run from New York City to Albany. Fulton proved the practicality of steamboat travel the following year when his rebuild boat began weekly trips between the two cities. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) The American System of Manufacturing Inventors A number of inventors working in different industries developed manufacturing processes that, taken together were more important than the products they manufactured. This came to be known as the “American System” – special purpose machines and standardized work processes that resulted in repetitive tasks that could be performed rapidly by relatively unskilled workers. This system gave American industry a competitive edge in the growing world economy. Eli Whitney (1765-1825) is best known for inventing the cotton gin, the machine that separated cotton seeds from cotton fiber. It revolutionized textile production, but was widely pirated, and Whitney never realized the wealth that should have been his. He also developed a precision process to make uniform parts that could be assembled interchangeably into finished guns – an achievement that was arguably as important as the cotton gin. Another important contributor to the “American System” was Cyrus Hall McCormick (18091884), who developed the grain reaper. This invention not only increased agricultural productivity – releasing surplus farm workers for growing industry – but also refined the efficiency of the manufacturing processes. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) Inventors (continued) Thomas Edison The most prolific inventor of all was Thomas Alva Edison (18471931), who differed from earlier inventors by using a sustained and organized invention process. In 1876, he combined his research laboratory with his manufacturing facility. From then until his death in 1931, he worked tirelessly to produce a steady flood of commercially viable products. General Electric The model for institutionalizing innovation was established by Charles Proteus Steinmetz (1865-1923), who fled Germany for New York in 1889, and obtained employment with an electrical equipment company. He soon founded his own laboratory, which in 1892 was acquired by the General Electric Co. In 1900 General Electric organized the first modern industrial research laboratory, and the following year it promoted Steinmetz to chief consulting engineer. Other companies, including DuPont, Corning Glass, Parke-Davis pharmaceuticals, and Eastman Kodak, soon had their own research laboratories, which would be the source of countless new products and processes over the coming years. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) Communications If commerce were to flourish in a country as large as the United States, there needed to be not only a large and efficient transportation system, but also a way to speed communications between far-flung areas. Initially, mail was conveyed by railroad; the Railway Mail Service was established in 1869 as a separate branch of the Post Office Department. But faster communications were needed – and, during the first half of the 19th century, a number of inventors in Europe and the United States worked on the problem of transmitting messages by means of electricity. The Telegraph Samuel Finley Breese Morse (1791-1872) believed that the flow of electricity could be made visible and that “intelligence” could be transmitted by wires across distances. He and other experts constructed a machine that transmitted electrical impulses through a wire that when drove another device at the other end to inscribe a series of dots and dashes on a moving strip of paper. Morse devised a code of dots and dashes for the letters of the alphabet. The system thus permitted messages to be sent almost instantaneously between two points. On May 24, 1844, the message, “What hath God wrought,” flashed from the nation’s capital to Baltimore and then back again. This was the beginning of the telegraph system and the coding that became known as “Morse Code.” Morse’s company, the Morse Electromagnetic Telegraphy Co., licenses his patent; the Western Union Telegraph Co. ultimately came to dominate long-distance telegraphic communications. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) Communications (continued) The Telephone If words could be transmitted by code, inventors soon realized that the voice itself might be transmitted, as well. Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922) developed a system that converted sound waves to a varying current of electricity. His father-in-law, Gardner Green Hubbard (1822-1897), submitted Bell’s patent application on February 14, 1876. It was granted on March 1, 1876; some have called it the single most valuable patent in history. In 1877 Hubbard headed a group that formed the Bell Telephone Company (later renamed American Bell), although Bell ultimately lost interest in further developing the technology. The Telephone System In 1880 Theodore Newton Vail (1845-1920) was hired to be the first general manager of American Bell. Vail envisioned linking all of the phones in the U.S. into one system. He started by persuading a potential competitor, Western Union, not to enter the telephone business, and he then acquired a controlling interest in Western Electric to provide technology and equipment for his countrywide network. In 1902 as head of American Telephone and Telegraph (a wholly owned subsidiary of American Bell), Vail successfully fought and bought out most of his competitors. He realized, however, that the monopoly he was creating would be vulnerable to government antitrust action. To forestall such action, he proposed a regulatory commission to monitor AT&T’s business, ceased acquiring competitors, and agreed to connect his longdistance lines with any local independent operator that wanted to be a part of the system. In return, the government agreed not to bring antitrust actions against the company. The agreement lasted until 1974, when the U.S. Justice Department filed an antitrust suit against AT&T – “Ma Bell” – which was then the world’s largest company. The company split itself into pieces, separating its longdistance and regional phone operations. The breakup launched competition within the telephone industry and eventually the telecommunications revolution. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) Entrepreneurs and Financiers Industrialization and the growth of the American economy in the 19th century created opportunities for many ambitious and talented entrepreneurs to become extraordinarily wealthy. Along with their wealth came power – the power to shape industries, and even the power to affect government. John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) played a central role in shaping the course of American industrialization. He established his own investment bank, J. P. Morgan & Co., in 1861. The railroad boom was on, and railroads required huge amounts of capital that Morgan began to provide. Morgan’s investment reach also extended to other industries; he underwrote Edison’s incandescent light, invested in Edison’s power generation and distribution plants, and in 1892 financed the creation of General Electric. His greatest achievement in industrial finance was the creation of the United Steel Corp., the largest industrial company in the world. Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) began investing at the age of 22 and established an iron works company in 1864. He used these early investments to create an empire of iron and steel. He relentlessly sought ways to reduce costs of production by gaining control of the entire process from mining the ore, transporting it to the plants, buying the coke to convert the ore, and then processing it with the latest technology. At the same time, he bought out competitors and combined them into an ever-larger empire. In early 1901, Carnegie sold his company to J. P. Morgan for the then unheard-of price of $480 million. Morgan combined Carnegie’s company with his own to form the United States Steel Co. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) John Davison Rockefeller (1839-1937) entered the refining business in 1863 – four years after the first oil well was drilled at Titusville, Pennsylvania, giving birth to the American petroleum industry. Cleveland soon became a major refining center, but Rockefeller disliked the disorderly and fragmented industry and moved to bring order to it. In 1870 he organized the Standard Oil Company; his strategy was to buy smaller companies and combine them into a company large enough to exert control over the market. By the end of 1872 Standard Oil had bought 34 competitors and controlled almost all of the refining companies in Cleveland; by 1879 the company controlled 90% of America’s refining capacity. In its search for a way of legally organizing its large and diverse business, the company tried a number of organizational structures. In 1882 it created the first modern trust in American history, the Standard Oil Trust in Ohio. But the Ohio attorney general brought suit against the trust, and in 1892 the Ohio Supreme Court annulled the charter. The company then moved the trust to New Jersey and renamed itself Standard Oil (New Jersey). By this time the company owned an estimated threefourths of all the petroleum business in the United States. The passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 intensified attention on the giant company, and it was constantly fighting efforts to break it up and limit its power. Court battles with the company continued until a Supreme Court antitrust decision of May 15, 1911, dissolved Standard Oil Trust and reorganized it into 38 companies. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) The Birth Of Marketing Industrialization not only created opportunities for mass production, but also led to the development of mass markets – and mass marketing. Mass Marketing Before the Industrial Revolution, products were mostly handcrafted and sold on a one-toone basis to customers. The mass production of consumer goods enabled retailers to sell quantities of similar products to a larger base of customers. Selling to mass markets required companies to communicate to all of their potential customers. Advertising, a small and scattered industry, began transforming itself into a sophisticated group of comparatively large companies. Retail Merchandisers The 19th century brought the ascendancy of merchandisers that combined distribution with mass marketing. The growing urban population provided a concentrated market for John Wanamaker (1838-1922), who saw an opportunity to create a new kind of store-the department store-that offered a wide variety of wares under a single roof. He build his business around customer loyalty and wrote and bought advertising that proclaimed his policies: a full guarantee on all merchandise, one price for all, payment in cash, and a cash refund if the customer was not happy. A different segment of the market beckoned to Frank W. Woolworth (1852-1919). In 1878, Woolworth was working in a store in Watertown, NY, when he helped to create a new five-cent counter. He grasped the potential of the idea of eliminating skilled, expensive clerks and replacing them with low-paid women clerks. The following year, 1879, Woolworth tested his idea with his first store in Utica, NY, but it failed because of a poor location That same year, he opened a similar store in Lancaster, PA, that was an immediate success. Despite early setbacks, Woolworth persevered and continued to expand. Selling many low-priced products, he relentlessly looked for low-cost merchandise, including toys, ornaments and glass goods from Europe. In 1900 he began to build a strong brand identity by creating uniform design for his 59 existing stores and by 1919 there were 1081 Woolworth stores in the US and Canada. The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind A Brief History of Business (in the U.S.) The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind