Aligning mHealth with U.S. National

Health IT Initiatives for HIV

Counseling in Non-Clinical Settings

*Macey L. Henderson, JD, Adam C. Knotts, MBA &

Martin C. Were, MD, MS

Acknowledgements

Academic & Research Advisors

Shaun Grannis, MD, MS

Malaz Boustani, MD, MPH

Dennis Watson, PhD

Paul Halverson, DrPh

Mobilify Technology

Michael Dowden, MBA

Andrew Roden, BS

Kigho Emenike, MPH

Marc Lane, JD, MBA

Tarik Rabie, MPH

Research Assistants

Braden Paschall

Kate Creager

Kaila Dunnick

Tyler Bowles

LaQuita Sparks

Christopher Huff

Christian Zimmerman

Learning Objectives

•

Learning Objective 1: Describe emerging role of mHealth in HIV

counseling, testing, and referral (CTR) within non-clinical setting, as a

demonstration of broad use of mobile technologies for public health

across multiple conditions.

•

Learning Objective 2: Explore national health IT standards and their

application for mHealth CTR tools that serve public health needs.

•

Learning Objective 3: Discuss the implications of FDA’s final guidance

on mobile applications, and current certification guidelines for health

information technologies on mHealth applications for public health,

using mHealth applications for HIV CTR as a reference use-case.

Commonly Used Acronyms

mHealth

IT

HIV

CTR

FTC

FDA

NIST

PHIN

RHIE

mobile health technology (for healthcare or public health)

information technology

human immunodeficiency virus

counseling, testing, and referral

Federal Trade Commission

Federal Food and Drug Administration

National Institute of Standards and Technology

Public Health Information Network

Regional Health Information Exchange

MOBILE APPS FOR

IMPROVED HIV CTR IMPACT

(photo credit: ROBYN BECK/AFP/Getty Images)

mHealth

• The use of mobile information and health IT for

improving population health outcomes:

- health promotion

- illness prevention

- health care delivery

- information systems

- workforce and training

• Has the potential to shift the paradigm on when,

where, how, and by whom health services are

provided and accessed

mHealth and HIV

•

HIV prevention, care, and treatment

•

mHealth tools support HIV priorities

including linkage to care, retention in

care, and adherence to ART

treatment

•

Short messaging services (SMS)

can be used for appointment and

medication reminders

•

Offers an opportunity to expand

health care services in areas with

limited resources

mHealth and HIV

• Mobile phones have the

potential to induce a paradigm

shift in resource-limited settings

by encouraging patients to stay

connected to health care

providers

• Will improve low-cost, highly

engaging, and ubiquitous

STD/HIV prevention and

treatment support interventions

“Just in one of our programs, we

did 1200 tests last year. That’s

1200 pieces of paper that have to

be entered into the system.

Instead of doing that, if we were

doing it on an iPad or whatever,

and that went into the system,

think of the steps we could save….

So those hours and dollars could

be spent doing more testing or

more outreach, saving the agency

money, you know, going into

something else.”

Enhanced Possibilities With a Mobile

Data Collection System in Nontraditional Settings

• Improved surveillance and

reporting

• Improved reach and public

health impact

Test Positivity Rates by setting (CDC, 2012)

Traditional

Non-Traditional

(Community Based

0.47%

0.82%

Dimensions of mHealth Technologies focused on HIV CTR

DEVELOPMENT

CONSIDERATIONS

FDA Regulations of Mobile Apps

•

MAY meet the definition of medical

device but for which FDA intends to

exercise enforcement discretion.

•

May be intended for use in the diagnosis

of disease or other conditions, or in the

cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention

of disease.

•

Even though these mobile apps MAY

meet the definition of medical device,

FDA intends to exercise enforcement

discretion for these mobile apps

because they pose lower risk to the

public.

Mobile apps that use patient

characteristics such as age, sex, and

behavioral risk factors to provide patientspecific screening, counseling and

preventive recommendations from wellknown and established authorities

[Appendix B].

Mobile apps that enable, during an

encounter, a health care provider to

access their patient’s personal health

record (health information) that is either

hosted on a web-based or other platform

[Added March 12, 2014].

National Health IT Standards

• Common standards and implementation specifications

recommended for electronic data exchange within

meaningful use guidelines

• The concept of meaningful use rested on the '5 pillars' of

health outcomes policy priorities, namely:

– Improving quality, safety, efficiency, and reducing health

disparities

– Engage patients and families in their health

– Improve care coordination

– Improve population and public health

– Ensure adequate privacy and security protection for personal

health information

Infrastructure and Workforce

eHealth Exchange

• National

HIE

• Community/Regional

EHR

• Local

• National initiative to increase the capacity of public health

agencies to electronically exchange data and information

across organizations and jurisdictions

• Promotes the use of standards

• Defines functional and technical requirements for public

health information exchange

www.healthit.gov

SUPPORTING EVIDENCE FOR

DEVELOPMENT OF NEW MOBILE

DATA COLLECTION SYSTEM

King et al. (2013) King, J. D., Buolamwini, J., Cromwell, E. A., Panfel, A., Teferi, T.,

Zerihun, M., & Emerson, P. M. (2013). A novel electronic data collection system for

large-scale surveys of neglected tropical diseases. PloS one, 8(9), e74570.

• Studied the collection of data using mobile technology.

• Results:

• Gained 265 person-days using mobile technology as seen in Table 1.1

• Able to collect more data in less time

• 12% decrease in data entry error pertaining to blank field in census

record (age, sex, availability)

• Cost of equipment was similar between both methods, though continual

use of mobile equipment suggested increased savings overtime

• Gave instant results and obviated the need for double-data entry and

cross-correcting, thus reducing errors

“Electronic data collection using an Android-based technology was suitable for a large-scale

health survey, saved time, provided more accurate geo-coordinates, and was preferred by

recorders over standard paper-based questionnaires”.

Onono, M. A., Carraher, N., Cohen, R. C., Bukusi, E. A., & Turan, J. M. (2011). Use

of personal digital assistants for data collection in a multi-site AIDS stigma study in

rural south Nyanza, Kenya. African health sciences, 11(3).

• Describes the development, cost effectiveness, and implementation in

a PDA Based electronic system to collect, verify, and manage data

from a multi-site study on HIV/AIDS.

• PDA programmed for collecting and screening eligibility study data and

responses to structured interviews on HIV/AIDS stigma.

Successes included:

1. Capacity building of interviewers (workforce development)

2. Low cost of implementation

3. Quick turnaround time of data entry with high reliability

4. Convenience

Advantages of Paper to Mobile Transition

Double data entry

• 265 person-days

were gained

• Final data set

available one

month sooner

Accuracy

• Electronic: 1.8%

error rate

(n=38,652)

• Paper: 2.3% error

rate (n=33,800)

King et al. (2013)

Cost & Security

Study Example

Onono 2011

King 2013

Paper Based

$10,313

$13,883

Electronic Based

$6,471

$10,320

Savings

$3,842

$3,563

One device was stolen

“The stolen PDA was not recovered, but because data on the SD card

were encrypted and the PDA password protected, participant privacy

(Onono, et. al., 2011)

was not compromised.”

“It has to be compatible with our

reporting system….If it’s just

another exercise in collecting data,

it doesn’t do us any good. It has to

be compatible.”

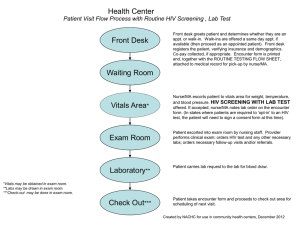

Designed from a Use-Case Analysis

A NEW PROPOSED PROCESS

Current

Process

Community Health

Worker (CHW)

Collects Client’s

Information on pen

and paper.

CHW reenters

info into 3rd

party webbased portal

3rd party

manages

data

Bi-annual

hard upload

to CDC

Proposed

Process

CHW collects

info via Mobile

Tablet

Encrypted

data

transmitted to

3rd party data

management

company

Data sent to CDC

Current

Process

Community Health

Worker (CHW)

Collects Client’s

Information on pen

and paper.

CHW reenters

info into 3rd

party webbased portal

Security

3rd party

manages

data

Bi-annual

hard upload

to CDC

Cost

Double data entry

Data Accuracy

Proposed

Process

CHW collects

info via Mobile

Tablet

NIST Compliant

Diminishing Resources Over Time

Encrypted

data

transmitted to

3rd party data

management

company

Saved man power

Data validity increases

Data sent to CDC

Lower cost

Comparison

• 3rd party web-based portal cost to

CDC and community

organizations

• Security concerns

– No audit trail for paper, unable

to identify data breach

– Paper process not secure –

increased risk to HIPAA

violations

• Double data entry

– Strain on already resourceconstrained organizations

“I see less likelihood of HIPAA

violations with electronic

forms, because with the paper

forms, currently, they take it

back and input it and it might

not be the same person taking

it back and putting it in. So you

have multiple people touching

the forms.”

Implementation Study Overview

• Aim 1: Develop mobile data collection system

• Aim 2: Pilot test (mixed-methods)

• Aim 3: Develop an implementation strategy for

scalability

Aim 1: Develop Mobile Data

Collection System

1) Design basic system components

2) Develop protocols and procedures

Methods:

– Literature reviews

– Observations

– Key informant interviews

3) Alpha Test user-interface

Aim 2: Pilot Testing: Deployment

to Community Based

Organizations

1) Determine appropriate baseline data

– Recommendation: 1 month field observations, or analysis of

2) Beta Test (small sample size (n=10)

– collect quantitative and qualitative data

Technical and workforce components

3) Develop a logic model to describe the

process and to inform implementation

strategy

Aim 3:Develop an Implementation

Strategy for Scalability

1) When developing the implementation

strategy, fidelity will be a key issue

2) Developing a fidelity tool

Could be a checklist, or a scale?

References

Muessig, K. E., Pike, E. C., LeGrand, S., & Hightow-Weidman, L. B. (2013). Mobile phone applications for the care and prevention of HIV and other sexually

transmitted diseases: a

review. Journal of medical Internet research, 15(1).

Heslop, L., Weeding, S., Dawson, L., Fisher, J., & Howard, A. (2010). Implementation issues for mobile-wireless infrastructure and mobile health care computing

devices for a

hospital ward setting. Journal of medical systems, 34, 509-518.

Veniegas, R. C., Kao, U. H., & Rosales, R. (2009). Adapting HIV prevention evidence-based interventions in practice settings: an interview study. Implementation

Science 4(1), 76.

Maiorana, A., Steward, W. T., Koester, K. A., Pearson, C., Shade, S. B., Chakravarty, D., & Myers, J. (2012). Trust, confidentiality, and the acceptability of sharing

HIV-related patient data: lessons learned from a mixed methods study about Health Information Exchanges. Implementation Science, 7(1), 34.

Littman-Quinn, R., Mibenge, C., Antwi, C., Chandra, A., & Kovarik, C. L. (2013). Implementation of m-health applications in Botswana: telemedicine and education

on mobile devices in a low resource setting. Journal of telemedicine and telecare, 19(2), 120-125.

Leon, N., Lewin, S., & Mathews, C. (2013). Implementing a provider-initiated testing and counselling (PITC) intervention in Cape town, South Africa: a process

evaluation using the normalisation process model. Implementation Science, 8(1), 97.

Lester, R. T., Mills, E. J., Kariri, A., Ritvo, P., Chung, M., Jack, W., & Plummer, F. A. (2009). The HAART cell phone adherence trial (WelTel Kenya1): a

randomized

controlled trial protocol. Trials, 10(1), 87.

Lester, R. T. (2013). Ask, Don't Tell—Mobile Phones to Improve HIV Care. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(19), 1867-1868.

Furberg, R. D., Uhrig, J. D., Bann, C. M., Lewis, M. A., Harris, J. L., Williams, P., & Kuhns, L. (2012). Technical Implementation of a Multi-Component, Text

Message–Based Intervention for Persons Living with HIV. JMIR Research Protocols, 1(2).

Hardy, H., Kumar, V., Doros, G., Farmer, E., Drainoni, M. L., Rybin, D., & Skolnik, P. R. (2011). Randomized controlled trial of a personalized cellular phone

reminder system to enhance adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS patient care and STDs, 25(3), 153-161.

Lester, R. T., Ritvo, P., Mills, E. J., Kariri, A., Karanja, S., Chung, M. H., ... & Plummer, F. A. (2010). Effects of a mobile phone short message service on

antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. The Lancet, 376(9755), 1838-1845.

CDC. (2010). Vital Signs: HIV Testing in the U.S. , from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/Vital-Signs-Fact-Sheet.pdf

CDC. (2011). Estimates of New HIV Infections in the United States, 2006-2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/HIV-Infections-2006-2009.pdf

CDC. (2012). Healthy People 2020 Leading Health Indicators: Objective HIV-13: Proportion of Persons Living with HIV Who Know Their Serostatus.

CDC. (2013). Assessment of 2010 CDC-funded Health Department HIV Testing Spending and Outcomes.

Seffah, A., Donyaee, M., Kline, R. B., & Padda, H. K. (2006). Usability measurement and metrics: A consolidated model. Software Quality Journal, 14(2), 159-178.