Constant Flow Community Water Supply in South Africa

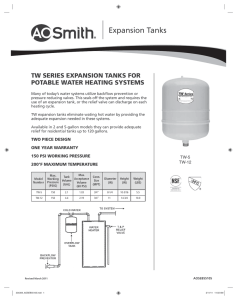

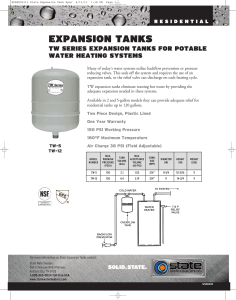

advertisement

Constant Flow Community Water Supply in South Africa Community Water Supply in South Africa pre-1994 South Africa divided into homelands, townships and white areas. DWAF responsible for water supply to formal sector. Water supply in homelands and townships responsibility of under-resourced and unrecognised ‘Banthusthan’ governments. Community Water Supply in South Africa post-1994 12 million with inadequate supply. DWAF now has responsibility of supply to all. New National Policy: Basic service provision a right. “Some for All” rather than “All for Some”. Water has economic value. The user pays. Basic Level of Service Minimum of 25 litres of potable per person per day. Supply point to be within 200 metres of each household. Reliability of 98%. Minimum flow of 10 litres per second. Infrastructure to be subsidised with O&M cost recovery. Problems with Conventional Basic Level of Service Culture of non payment due to historical subsidisation. Low reliability. Inappropriate levels of service. Demand levels lower than design supply. Poverty. Lack of community participation in planning. Lack of planning for O&M. Communities gave high priority to water supply access. Lack of capacity to provide and manage conventional full pressure household supply system. Significant demand for low capital cost household water supply with low energy demand. Free basic level of supply made policy in 2000. Constant Flow Systems Reticulation networks that supply water at a constant rate to distributed household tank storages. Constant rate maintained by constraint mechanisms. Flow independent of consumption patterns. Design for peak flows not required. Reticulation pipe sizes and main storages can be reduced. Constant Flow System Options Trickle feed systems. LW tank system. Manual operated system. Flow control valve systems. Mechanical flow constraint valves. Mechanical constant flow valves. Electronic flow control valves. Trickle Feed Systems LW Tank Systems Manually Operated Systems Yard Tank Options Plastic tanks Concrete tanks Concrete Tanks Concrete Tanks Plastic Tanks International Experience Australia and New Zealand utilised for more than 40 years in scattered rural communities. recently subject of WSUD research and utilised in new developments. Kiribati, South Pacific pilots in water scarce environments Kiribati South African Pilot Programme Implementation in 13 communities (peri-urban to deep rural) to assess feasibility. Objectives: Describe and document technology. Monitor and evaluate implementation and 1 year of operation and maintenance. Economic, technical and social. Assess feasibility and document lessons learnt. Pilot Projects Financial M&E Results Technical M&E Results Increased consumption (average of 14 l/cap./day compared to national average of 7 l/cap./day). Decrease in system losses (average of 12% compared to national range of 30-60%). Low maintenance requirements. Social M&E Results Tampering and illegal connections reduced to almost zero. High cost recovery (up to 90%). Feasibility Analysis Benefits: Low cost of high level of service. Increased health and hygiene benefits. Simple administration requirements. Options for yard tanks. Low maintenance requirements. Low losses. Equitable distribution. Increased supply security. Feasibility Analysis Constraints: Limited daily flow. Community acceptance. Bureaucratic acceptance. Reduced tolerance to suspended matter. Hot water and algae growth. Perceived risk of tampering and illegal connections. Further Research Required Increase information dissemination. Concrete tanks. M&E of consumption and loss patterns. Options for upgrading level of service at household level. The End