2014-02-20 Group 4 Compilation of PPTs for IP Inn of Court

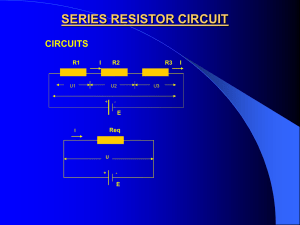

advertisement

IP CASES TO WATCH 2014 Seattle IP Inn of Court – Group 4 Introduction Shannon Jost Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc. Shannon Jost Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd v. CLS Bank Int’l Tim Seeley Highmark, Inc. v. AllCare Health Mgmt. Sys.; Icon Health & Fitness, Inc. v. Octane Fitness, LLC Paul Leuzzi Limelight Networks, Inc. v. Akamai Tech., Inc. David Binney, Antoine McNamara POM Wonderful LLC v. The Coca-Cola Co., B&B Hardware v. Hargis Indus. Alina Morris Stacie Foster Lisa Finkral Lighting Ballast Control v. Phillips Elec. Kirk Johns Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. Tonya Gisselberg J. Bowman Neely Wrap-Up and Questions Agenda Carmen Wong Julianne Henley Subject Technology: Heart rate monitor that measures heart rates by processing ECG signals. Claimed invention included electronic circuitry. Claim 1 is representative and recites, in relevant part: A heart rate monitor for use by a user in association with exercise apparatus and/or exercise procedures, comprising: an elongate member; electronic circuitry including a difference amplifier having a first input terminal of a first polarity and a second input terminal of a second polarity opposite to said first polarity; said elongate member comprising a first half and a second half; a first live electrode and a first common electrode mounted on said first half in spaced relationship with each other; a second live electrode and a second common electrode mounted on said second half in spaced relationship with each other; said first and second common electrodes being connected to each other and to a point of common potential . . . . Nautilus v. Biosig Instruments Nautilus – “spaced relationship”? 35 U.S.C. § 112 ¶ 2: “the specification shall conclude with one or more claims particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming the subject matter which the inventor or a joint inventor regards as the invention.” Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc.: “[t]he limits of a patent must be known for the protection of the patentee, the encouragement of the inventive genius of others and the assurance that the subject of the patent will be dedicated ultimately to the public.” Otherwise, a “zone of uncertainty which enterprise and experimentation may enter only at the risk of infringement claims would discourage invention only a little less than unequivocal foreclosure of the field,” and “[t]he public [would] be deprived of rights supposed to belong to it, without being clearly told what it is that limits these rights.” 517 U.S. 370, 390 (1996) (quoting General Electric Co. v. Wabash Appliance Corp., 304 U.S. 364, 369 (1938); United Carbon Co. v. Binney & Smith Co., 317 U.S. 228 (1942); Merrill v. Yeomans, 94 U.S. 568, 573 (1877). Nautilus- Indefiniteness Standards • District Court: Claim element requiring electrodes to be in a “spaced relationship” with each other was indefinite • Federal Circuit: Although the claim term wasn’t expressly defined in the specification, the “claim language, specification and figures” of the asserted patent “provide[d] sufficient clarity to skilled artisans as to the bounds of this disputed term.” • A claim term is indefinite only when it is “not amenable to construction” or “insolubly ambiguous.” • A claim is not indefinite under § 112 so long as a court can find that the claim has some discernable meaning, and is not “insolubly ambiguous” even when the claim is capable of multiple reasonable interpretations. Nautilus – Lower Courts (1) Whether the Federal Circuit’s acceptance of ambiguous patent claims with multiple reasonable interpretations – so long as the ambiguity is not “insoluble” by a court – defeats the statutory requirement of particular and distinct patent claiming; and (2) Whether the presumption of validity dilutes the requirement of particular and distinct patent claiming. Nautilus – Questions Presented • Under Federal Circuit standard, scope of patent may not be known until claim is construed by court. Claim did not provide clear notice, on its face, of what it covered. Shouldn’t the public know what a patent covers at the time of issuance? Must we wait for appeal? • If “reasonable persons [may] disagree” about the proper scope of a patent claim, how should the public proceed? • If a claim may be definite where the court can discern its function, without clearly claiming how to perform that function, does the patent claim preempt all solutions which address that function? • Unclear and overbroad patents are key contributor to ballooning expense and frequency of patent litigation. Nautilus – Representative Petitioner and Amici Arguments Predictions – What will SCOTUS do? • 35 U.S.C. § 101: “Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l • Asserted claims generally directed to a computerized method for performing a “form of escrow” designed to mitigate the risk that only one party to a financial transaction will perform its contractual obligations at settlement. • Claims recite computer-implemented methods of settling financial transactions, as well as computer-readable media capable of storing, and generic computer systems capable of running, programming instructions for performing the claimed method. • The patents do not disclose or claim the specific programming required to implement the claimed methods. • District Court: No patentable claims. CLS – Claimed Invention and Lower Court Ruling (1) “What test should the court adopt to determine whether a computer-implemented invention is a patent ineligible ‘abstract idea’; and when, if ever, does the presence of a computer in a claim lend patent eligibility to an otherwise ineligible abstract idea?” and (2) “In assessing patent eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101 of a computer-implemented invention, should it matter whether the invention is claimed as a method, system, or storage medium ...?” CLS – Questions before en banc CAFC • 6 separate opinions, none endorsed by a majority. • 5-5 split as to whether Alice’s claims to computer system inventions were patentable (leaving in place the lower court’s SJ that they were nonpatentable). • Alice’s remaining claims held non-patentable, but based on different, conflicting reasons. • No clear legal standard emerged as to whether, and when, computer-implemented inventions are patentable. CLS –en banc CAFC Whether claims to computer-implemented inventions—including claims to systems and machines, processes, and items of manufacture— are directed to patent-eligible subject matter within the meaning of 35 U.S.C. § 101 as interpreted by this Court? CLS – Question Presented - SCOTUS Predictions – What will SCOTUS do? The Fee-Shifting Dash Congress vs Courts Paul W. Leuzzi Weyerhaeuser Company Seattle IP Inn of Court - February 20, 2014 Brief History 35 U.S.C. §285 The court “in exceptional cases may award reasonable attorney fees to the prevailing party” Exceptional Willful infringement or inequitable conduct Otherwise, only if both: The litigation is brought in subjective bad faith, and The litigation is objectively baseless Clear and convincing evidentiary standard Standard of Review on Appeal Exceptional determination – abuse of discretion/clear error Award of attorney fees – abuse of discretion §285 Under Pressure Today Abusive Litigation Difficult to end case early, even when weak Bad actors seek to increase litigation costs to pressure settlements Deadweight to economy Rarity of Fee Awards Only about 1% of cases Supreme Court Deciding two cases, oral argument on February 26th Congressional Activity At least 12 bills introduced relating to patent litigation 4 have fee provisions and 3 seek to amend Rule 11 Judicial Pronouncements Chief Judge Radar’s Op-Ed in the New York Times (June 4, 2013) States §285 gives judges authority to curtail abusive litigation Directs District Judges to seek out more opportunities to award fees Octane Octane Fitness v Icon Health & Fitness District Court Icon (a large company) sued Octane (a start-up) for infringement of its patented linkage system for elliptical machines. After claim construction Octane was granted summary judgment, finding multiple claim limitations missing from the accused device. District court denied Octane’s motion for fees under §285 as not being objectively baseless. Federal Circuit Affirmed judgment and denial of fees. No reason to revisit standard for exceptionality. Rehearing en banc denied. Octane Octane Fitness v Icon Health & Fitness Question Presented: Whether a district court, in exercising its discretion to award attorney fees in exceptional-cases under §285, should use traditional equitable factors…rather than the Federal Circuit’s rigid test requiring both objective baselessness and subjective bad faith? Equitable Factors: Consistent with Supreme Court rulings and Copyright and Lanham Acts. District courts discretionary authority should not be improperly appropriated by federal Circuit. Goverment supports return to pre-Brooks “totality of circumstances” test. Need to address litigation abuse. Brooks Test: Courts should require misconduct. Fee shifting implicates First Amendment. Highmark Highmark Inc. v. Allcare Health Management Systems, Inc. District Court Ruled for Highmark on its DJ of non-infringement, invalidity and unenforceability of Allcare’s patents covering heath management system. Allcare, a patent assertion entity, counterclaimed for infringement of 3 claims, 1 of which was subsequently withdrawn. Federal Circuit Affirmed without written opinion. District Court Granted motion for exceptional case and award for fees and sanctions under Rule 11. Federal Circuit Held objective baselessness is a question of law subject to de novo review. Affirms for withdrawn claim but reverses asserted claim objectively baseless and that Allcare’s actions, when considered separately, amount to misconduct. Rehearing en banc denied. Highmark Highmark Inc. v. Allcare Health Management Systems, Inc. Question Presented: Whether a district court’s exceptional-case finding under §285, based on its judgment that a suit is objectively baseless, is entitled to deference? Deferential Review: Consistent with Supreme Court precedent under EAJA and Rule 11 District courts best suited to evaluate entire record and make decision. Preserves resources by discouraging appeals. De Novo Review: Consistent with de novo review of claim construction on which objectively baselessness will depend. Federal Circuit has expertise to make a legal determination Enhances uniformity and therefore predictability. Congressional Activity 12 Bills Pending in Congress. 4 Have Fee Provisions. 3 Seek to Amend Rule 11. The Federal Circuit Chief Judge Rader’s 2013 Op-Ed. Kilopass. December, 2013 Panel Decision. Court not persuaded that objective baselessness imposes too great of a burden. Bad faith determination is based on the “totality of the circumstances”. Bad faith can be inferred. Questions whether bad faith should be a requirement clear and convincing standard but as a panel decision is unable to change. QUESTIONS? 2014: Eye on the Supreme Court Akamai vs. Limelight Can patent infringement be induced if no single entity is liable for direct infringement? Direct Infringement 1. A method for . . . comprising: A • • • • generating . . . ; transmitting . . . ; receiving . . . ; playing . . . . Induced Infringement B A 1. A method for . . . comprising: • • • • generating . . . ; transmitting . . . ; receiving . . . ; playing . . . . 35 U.S.C. § 271(b): “Whoever actively induces infringement of a patent shall be liable as an infringer” Divided Infringement B A 1. A method for . . . comprising: • • • • generating . . . ; transmitting . . . ; receiving . . . ; playing . . . . No single entity performs all of the limitations. No one is liable for direct infringement. Divided Infringement w/ Inducement Limelight B A 1. A method for . . . comprising: • • • • generating . . . ; transmitting . . . ; receiving . . . ; playing . . . . What if B induces A to perform all of the method steps that B does not itself perform? Before Akamai • “Indirect infringement requires, as a predicate, a finding that some party amongst the accused actors has committed the entire act of direct infringement.” – BMC Resources, Inc. v. Paymentech, LP, 498 F.3d 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2007) Akamai — Majority • BMC Resources overruled – “[T]hat there can be no indirect infringement without direct infringement . . . is well settled.” – “[But] [r]equiring proof that there has been direct infringement . . . is not the same as requiring proof that a single party would be liable as a direct infringer.” • “[A]ll the steps of a claimed method must be performed . . . to find induced infringement, but . . . it is not necessary to prove that all the steps were committed by a single entity.” Akamai — Majority (cont’d) • Policy argument – “It would be a bizarre result to hold someone liable for inducing another to perform all of the steps of a method claim but to hold harmless one who goes further by actually performing some of the steps himself.” • Textual argument – 35 U.S.C. § 271(b) (“Whoever actively induces infringement of a patent shall be liable as an infringer”). Akamai — Linn Dissent • How can there be direct infringement if there is no direct infringer? • Vicarious liability is sufficient to protect patent holders and prevent gamesmanship • Even if vicarious liability were not sufficient, it is the job of Congress, not the Court, to fix the law Akamai — Newman Dissent • Agrees with Judge Linn that inducement cannot occur unless a single entity directly infringes • But Newman would find direct infringement even where no single entity performs all of the steps – “Infringement is not a question of how many people it takes to perform a patented method.” • Under Newman’s approach, Limelight could be liable for both direct and induced infringement Akamai — SG’s amicus brief • Fed. Circuit majority opinion has “intuitive force” – “As a matter of patent policy, there is no obvious reason why a party should be liable for inducing infringement when it actively induces another party to perform all the steps of the process, but not liable when it performs some steps and induces another party to perform the rest.” • Also agrees that vicarious liability is insufficient – Reversing the Fed. Cir. “will likely permit vendors such as Limelight to avoid liability altogether” • But fixing the mess in Congress’ job, not the Court – “That statutory gap is unfortunate, but it reflects the better reading of the current statutory language in light of established background principles of vicarious liability.” Akamai — Other Amici • This is really bad for us because… • Altera – Fed. Cir. decision introduces uncertainty in business; potential liability despite apparent non-infringement – Intent requirement could be met by defendant continuing activity post-suit • Google – Federal Circuit decision gives trolls a new weapon – Permits liability for practicing prior art • CTIA – Federal Circuit decision encourages bad claims-drafting POM Wonderful LLC v. The Coca Cola Company Case Summary by: Julianne Henley & Carmen Wong Presented by: Stacie Foster POM Case • Background: Coca Cola’s Product – Coca Cola released a MINUTE MAID branded drink labeled “Pomegranate Blueberry Flavored Blend of 5 Juices” (“Juice Drink”). POM Case • Background: Coca Cola’s Product Ingredients – 99.4% Apple & Grape Juices – .3% pomegranate juice – .2% blueberry juice – .1% raspberry juice POM Case • Background: Coca Cola’s Product Ingredients – Product named “Pomegranate Blueberry Flavored Blend of 5 Juices – The word “pomegranate” and “blueberry” were in larger font than the rest of the name – All 5 fruits were prominently illustrated on the label of Coca Cola’s Juice Drink POM Case • Background: POM’s Product – POM sells POM WONDERFUL branded drinks including pomegranate and pomegranate blueberry juices. POM Case • 11/26/08: POM sues Coca Cola in C.D. Cal. – False advertising (Lanham Act & Cal. BPC) – Statutory Unfair Competition (Cal. BPC) – POM: Coca Cola’s product misled consumers into believing it was mostly made of pomegranate and blueberry juices POM Case • District Court & 9th Circuit: – The District Court & 9th Circuit held that the Federal Food, Drug, & Cosmetic Act (FDCA) preempted POM’s Lanham Act claims against Coca Cola’s Juice Drink (as well as state law claims to the extent they conflicted with the FDCA). POM Case • SCOTUS: whether 9th Circuit Court erred in holding that a private party cannot bring a Lanham Act claim challenging a product label regulated under the Federal Food, Drug, & Cosmetic Act. POM Case • POM’s Arguments: – The Lanham Act and FDCA are not in “irreconcilable conflict” • Circuit Split: – 3rd, 8th, and 10th recognize false labeling & advertising claims under the Lanham Act – 9th: FDCA preempts these claims POM Case • Coca Cola’s Argument: – Circuits are not in conflict -- the cases POM relies on outside the 9th Circuit did not address the FDCA’s preemption of the Lanham Act. – Government has adequate resources to regulate food and beverage labels and should be permitted to do so. POM Case • Solicitor General’s Amicus Brief: – Urged the Supreme Court not to grant Certiorari – FDCA is not “privately enforceable” and permits manufacturers to use truthful flavoring names on food and beverage labels. B & B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis Industries Inc. Presented by: Stacie Foster and Alina Morris B & B Hardware v. Hargis Indus. • B & B Hardware: – Mark: – Goods: – Use: – Registered: SEALTIGHT industrial fasteners for the aerospace industry 1990 1993 B & B Hardware v. Hargis Indus. • Hargis Industries: – Mark: – Goods: – Use: – Filed: – Refused: SEALTITE self-drilling, self-taping screws for use in the metal-building industry 1992 1996 B&B, and merely descriptive B & B Hardware v. Hargis Indus. • 1997: Hargis petitions to cancel B&B – Abandonment – Priority • 1998: B&B sues Hargis in Arkansas • Cancellation suspended • 2000: Arkansas Court – B&B’s mark descriptive and unregistrable – Didn’t reach likelihood of confusion B & B Hardware v. Hargis Indus. • 2001: Cancellation resumes, Hargis amends B&B to include descriptiveness claim • 2001: Hargis’ Examiner withdraws refusal over B&B registration – Hargis submitted Ark. descriptiveness decision • 2002: Hargis’ Examiner withdraws descriptiveness refusal – Hargis submitted acquired distinctiveness claim B & B Hardware v. Hargis Indus. • 2002: Hargis app publishes • 2003: B&B opposes Hargis app • 2003: Hargis’ amended petition to cancel B&B deemed untimely by TTAB – Petition amended 5+ years post registration – Knew/should have known basis for descriptiveness claim from the outset • 2003: Hargis’ cancellation of B&B dismissed B & B Hardware v. Hargis Indus. • 2006: B&B sues Hargis in Arkansas again • 2007: TTAB sustains B&B’s opposition – Likelihood of confusion – Priority – No issue preclusion from Arkansas • Ark. didn’t consider likelihood of confusion • B&B’s mark is now incontestable B & B Hardware v. Hargis Indus. • B&B’s Second Arkansas Suit Continues! – B&B argues 2007 TTAB decision should have preclusive effect – B&B argues 2007 TTAB decision should at least have deference and be part of evidence • Ark. Court: no preclusion or inclusion • Ark. Jury: no likelihood of confusion • 8th Circuit: TTAB not preclusive on LoC B & B Hardware v. Hargis Indus. • B&B: TTAB preclusion or deference: – LoC Factors – Facts found – Market considered – Same ultimate issue – TTAB experts – Enforce repose B & B Hardware v. Hargis Indus. • Hargis: no preclusion or deference: – Messy history – 4 different tribunals – Different info. – LoC standards – Article I vs. Article III Ct. Petrella v. MGM or Don’t be that lame, then tell me laches doesn’t apply. Tonya Gisselberg and J. Bowman Neely Case time line • 1963 & 1973 – Frank Peter Petrella and boxer Jake LaMotta create a book and 2 screen plays based on LaMotta’s life. • 11/19/1976 – Copyrights assigned by Petrella and LaMotta. • 1980 – United Artists released Raging Bull. • 1981 – Frank Petrella died. • 1991 – Paula Petrella filed a renewal application for the 1963 screen play. • 7 year gap. • 1998 – Petrella’s attorney informed the defendants of their copyright infringement. • 1998 – 2000 Letters exchanged regarding the infringement. • 9 year gap. • 2009 – Petrella sued MGM, UA and others for copyright infringement. Ninth Circuit Ruling We hold that Petrella’s copyright, unjust enrichment and accounting claims are barred by laches, and we therefore affirm the district court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of the defendants. Petrella v. MGM, 695 F.3d 946, 957 (2012). Petrella abandoned her non-copyright claims on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. Relief requested by Petrella from the U.S. Supreme Court • Petrella filed suit on 1/6/2009. • In light of the three-year statutory limitations period, Petrella sought damages and injunctive relief for acts of infringement occurring on or after January 6, 2006. Copyright Act civil statute of limitations No civil action shall be maintained under the provisions of this title unless it is commenced within three years after the claim accrued. 17 U.S.C. §507(b). Laches Laches is an equitable defense that prevents a plaintiff, who with full knowledge of the facts, acquiesces in a transaction and sleeps upon his rights. Elements of the defense: (1) the plaintiff delayed in initiating the lawsuit; (2) the delay was unreasonable; and (3) the delay resulted in prejudice. Circuits Split re Laches in Copyright Cases • Fourth Circuit – no laches. • Eleventh Circuit – strong presumption of timeliness if suit filed within the statutory period. Laches available only in extraordinary circumstances. • Second Circuit - laches is available as a bar to injunctive relief but not to money damages. • Sixth Circuit – laches is available in only “the most compelling of cases.” • Ninth Circuit - laches can bar all relief, both legal and equitable Petrella frames the issue before the U.S. Supreme Court Whether the nonstatutory defense of laches is available without restriction to bar all remedies for civil copyright claims filed within the threeyear statute of limitations prescribed by Congress, 17 U.S.C. § 507(b). Petrella’s Arguments • Petrella’s claims for relief should not be completely barred. • Congress has prescribed the time allowed for bringing copyright infringement suits and courts may not impose additional timeliness doctrines, such as laches. • Laches cannot bar either injunctive relief or damages for copyright infringement, as it would result in uncompensated compulsory licenses and laches cannot limit legal, as opposed to equitable, remedies. • Precluding laches provides the benefits of preventing evidentiary concerns from trumping heirs’ copyrights, reducing needless litigation by copyright holders and protecting against financial prejudice through the equitable estoppel doctrine. MGM’s Arguments • Federal courts have the inherent equitable power to apply laches in all civil actions. • Congress intended that federal courts would apply laches in copyright cases. • Laches may bar an entire claim regardless of the relief sought. • Petitioner’s entire claim is barred by her unreasonable delay and the resulting prejudice. Justices’ Comments Justice Alito – The copyright statute of limitations says you can’t do it (bring a claim) unless it’s within 3 years. It doesn’t say that if it’s within 3 years, you’re home free. Justice Sotomayor – In terms of injunctive relief, given their reliance on your failure to act for 18 years, they shouldn’t be put out of business and told that they can’t continue in their business. Justices’ Comments cont. Justice Kagan – You don’t have very many cases where courts have applied laches as against the statute of limitations, but that’s because you can’t think of many instances in which it would be considered unfair to take the entire statute of limitations to bring a suit. Justice Breyer – Who in their right mind would go ahead and make this year after year if a huge amount of money is going to be paid to this copyright owner who delayed for 30 years and didn’t even seem to own it. Justices’ Comments cont. Justice Kennedy – Estoppel applies. Why isn’t laches just a first cousin of estoppel? Estoppel is an affirmative misrepresentation. Why isn’t laches here almost a misrepresentation? Justice Sotomayor – Your complaint is not against the witness dying. Your complaint is about what Congress does, which is to give a person the right to keep a copyright or renew it when the individual with whom you probably dealt with is dead. That’s always going to be the case. Justices’ Comments cont. Justice Ginsburg – Why is it unreasonable for the plaintiff to wait to see if the copyright is worth anything?