Incorporating Trauma into PBIS & Teacher Management

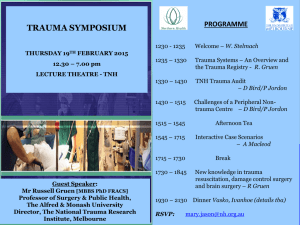

advertisement

Incorporating Trauma into PBIS & Teacher Management Chris Dunning, Ph.D. Professor Emerita University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee cdunning@uwm.edu Trauma and Learning Who could be the trauma student here? Children who do not feel safe live in a state of emergency. Their energy is consumed by crisis, making it impossible for them to focus on learning. From “Too Scared to Learn” by Jenny Horsman, 2000 ANSWER: Either Implications for Learning “Traumatized children often spend so much time in the lower level brain in a state of fear that they consistently focus on non-verbal vs. verbal cues.” Children who have experienced trauma also experience: More school nurse visits/School absences Referral to school speech pathologist/support services More Disciplinary Actions/Suspension from school More aggressive or non-attentive in school Difficulties with peers, teachers, and staff Lower performance and grade point averages Higher drop-out rates • “The school setting can be a battleground in which traumatized children’s assumptions of the world as a dangerous place sabotage their ability to develop constructive relationships with nurturing adults. Unfortunately, many traumatized children adopt behavioral coping mechanisms that frustrate educators and evoke exasperated reprisals, reactions that both strengthen expectations of confrontation and danger and reinforce a negative self-image. • Traumatized children’s behavior can be perplexing. Prompted by internal states not fully understood by the children themselves and unobservable by teachers, traumatized children can be ambivalent, unpredictable and demanding. But it is critical to underscore that traumatized children’s most demanding behavior often originates in feelings of vulnerability.” (Helping Traumatized Children Learn, p. 32-33) Trauma-Informed Educator Practice The trauma-informed educator: • Understands the impact of trauma on a child’s behavior, development, relationships, and survival strategies • Can integrate that understanding into planning for the child and learning • Understands his or her role in responding to child traumatic stress 5 What Can an Educator Do? • Recognize that exposure to trauma occurs to many children, not just those in protective or foster care. • Recognize the signs and symptoms of child traumatic stress and how they vary in different age groups. • Recognize that children’s “bad” behavior is sometimes an adaptation to trauma. • Understand the impact of trauma on different developmental domains. 6 What Can an Educator Do? • Understand the impact of trauma and PTSD on learning. • Understand the cumulative effect of trauma. • Gather and document psychosocial information regarding all traumas in the child’s life to make better-informed decisions. • Lessen the risk of system-induced secondary trauma by serving as a protective and stress-reducing buffer for children: – Develop trust with children through listening, frequent contacts, and honesty in order to mitigate previous traumatic stress. – Understand that schools would do well to be proactive about trauma rather than reactive. Trauma-Informed Educator • Offers interventions that increase self worth, • Forms strong relationships to enhance sense of trust, • Emphasizes the relationship consequences of behaviors, • Build up avenues for achievement and hope, • Helps child learn both emotion management skills and relationship skills, • Teaches how to calm biology to increase ability to think. Essential Elements of TraumaInformed education 1. Maximize the child’s sense of safety. 2. Assist children in reducing inappropriate hyperarousal and/or dissociation. 3. Address the impact of trauma and subsequent changes in the child’s behavior, learning, development, and relationships. 4. Utilize comprehensive assessment of the child’s trauma experiences and their impact on the child’s development and behavior to guide services. 9 5. Coordinate services with other agencies. Maximizing Safety: Understanding Children’s Responses • Children who have experienced trauma often exhibit extremely challenging behaviors and reactions. • When we label these behaviors as “good” or “bad,” we forget that children’s behavior is reflective of their experience. • Many of the most challenging behaviors are strategies that in the past may have helped the child survive in the presence of abusive or neglectful caregivers. 10 Maintaining safety • Behavior management based on selfregulation rather than compliance – Conflict resolution – Problem-solving – Compromise • Create positive peer culture – Reduce or prevent isolation/bullying – Increase social competence • Understand child’s need for containment • Providing positive behavioral supports – Identify triggers that set child off – Consistency and structure – Involve child, especially feedback PBIS • Assumes that approximately 80% of students can and will behave well if – 1) there are clear behavioral expectations – 2) they are taught how to behave in effective and ongoing manners. “Insights from Trauma-Informed Care help us to understand that it is just as important, if not more so, to focus on students’ emotional responses as their behavioral responses. Behavior may often communicate a student’s emotional need.” White and Dibble (2012) Wisconsin DPI Using Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS) to Help Schools Become More Trauma-Sensitive Paradigm Shift • Understanding that trauma is not a cognitive experience, but a sensory one, dictates strategies that immediately restore, to victims, a sense of safety and renewed sense of empowerment/control in the face of fear and uncertainty generated by the incident. • Reduction of the arousal level is critical to the restoration of pre-trauma cognitive processes, learning functions, behavior and performance. Trauma and School • Trauma can trigger (arouse) the activation of the autonomic nervous system to ready itself to resist or solve the real or perceived threat presented by exposure to an incident such as….. • If the response (arousal) is not discharged or deactivated, the sustained arousal state can lead to sustained cognitive and behavioral dysfunction. • Trauma being a sensory experience, arousal is experienced as an absence of the “sense of safety” and as a “sense of powerlessness.” • Aggressiveness, over reactive responses and exaggerated withdrawal are survival behaviors – attempts to feel safe, in control. What This Tells Us • As long as a student is not feeling safe and in control, this aroused state makes it difficult to process verbal information, attend, focus, retain and recall. • Intervention designed to deactivate the arousal state and return the student to a sense of safety and a sense of power or control, helps to restore previous cognitive and behavioral patterns. • The most immediate, short-term and long-term intervention, therefore, must be designed to restore that sense of safety and control. Why use the PBIS Triangle for Traumatized Students? Hierarchy of Brain Function Bruce Perry M.D., Ph.D. 1997 In the brain of someone who has experienced a variety of emotional, behavioral and cognitive stimuli, a “top heavy” ratio develops. In this ratio, the brain matures to moderate the more primitive instincts of the midbrain/brainstem. Bruce Perry M.D., Ph.D. 1997 When key experiences (Which develop the cortical/limbic part of the brain) are absent or minimal, the “higher” to “lower” brain ratio is impaired. In this case, the ability of the brain to moderate impulsive, reactive responses and to work through frustration is diminished significantly. Bruce Perry M.D., Ph.D. 1997 Children raised in environments characterized by domestic violence, physical abuse or other persistent trauma will develop an excessively active midbrain/brainstem. This results in an overly active and reactive stress response and a predisposition to aggression and impulsiveness. Bruce Perry M.D., Ph.D. 1997 When the developing brain is both deprived of sensory stimuli and experiences traumatic stress, the brainstem/ midbrain to cortical/limbic ratio is profoundly altered. Bruce Perry M.D., Ph.D. 1997 The Child’s Brain Differences due to Psychological Trauma Memory Normally coordinated and cohesive Explicit Memory Left Brain Implicit Memory Right Brain • Facts • Details • Who, what, where, when, how • Tied to Language • Emotional Memory • Senses-smells, sounds, etc. • Tied to Fight, Flight, Freeze Response Memory and Traumatic Stress Trauma Uncouples Integration of Memory I feel a certain way and I don’t know why!! Fight/Flight/Freeze • Overdevelopment of regions of the brain involved in anxiety and fear responses And • Underdevelopment of regions of the brain involved in complex thought and those necessary for learning. Implications for Learning • Traumatized children often spend so much time in the lower level brain in a state of persisting fear that they consistently focus on non-verbal vs. verbal cues • May be very intelligent but can’t learn easily→must do verbal learning when calm • •Learning needs to be more experience-based ⇒ → when traumatized children are stressed they are reactive/reflexive vs. accessing cognitive solutions Implications for Behavior • During early development, these traumatized children spent so much time in a low-level state of fear that they were focused primarily on non-verbal cues. • Once out of such an environment, it is still difficult for the child's brain to interpret (relearn) these innocent looks and touches as benign. These children are often labeled as learning disabled. • Difficulties with cognitive organization contribute to a more primitive, less mature style of problem solving -with violence often being employed as a "tool.“ • A traumatized child -- in a persistent state of arousal -can sit in a classroom and not learn. • The brain of this child has different areas activated -different parts of the brain controlling his functioning. • The capacity to internalize new verbal cognitive information depends upon having portions of the frontal and related cortical areas activated, which in turn requires a state of attentive calm. • This is a state that the traumatized child rarely achieves. Conduct Disorders Behavior is the language of trauma. Most children lack the language skills needed to describe how they are suffering, so they use behavior to express themselves. Most behaviors used by children to express themselves are considered “negative” behaviors. Cortical Modulation Is AgeRelated • The capacity to moderate frustration, impulsivity, aggression, and violent behavior is age-related. • With sufficient motor, sensory, emotional, cognitive, and social experiences during infancy and childhood, the mature brain develops (in a use-dependent fashion) a mature, humane capacity to – tolerate frustration – contain impulsivity – channel aggressive urges. Outcome • When a child is threatened, he or she is likely to act in an "immature" fashion. • Regression, a retreat to a less-mature style of functioning and behavior, is commonly observed in all of us when we are physically ill, sleepdeprived, hungry, fatigued, or threatened. • When we regress -- in response to a real or perceived threat -- our behavior is mediated (primarily) by less-complex brain areas. Baseline State of Arousal If a child has been raised in an environment of persistent threat, the child will have an altered baseline such that the internal state of calm is rarely obtained. The traumatized child will have a "sensitized" alarm response, over-reading verbal and non-verbal cues as threatening. Increased reactivity will result in dramatic changes in behavior in the face of seemingly minor provocative cues. Over-reading of threat will lead to a "fight or flight" reaction and impulsive violence. The child will view his violent actions as defensive. Change in “thermostat” • Children exposed to significant threat will "re-set" their baseline state of arousal such that even when no external threats or demands are present, they will be in a physiological state of persistent alarm. • As external stressors are introduced (e.g., a complicated task at school, a disagreement with a peer) the traumatized child will be more "reactive." • Even a relatively small stressor can instigate a state of fear or terror. • The cognition and behavior of the child will reflect his or her state of arousal. The Threat Recurs: Chronic Hyperarousal Traumatic Reenactment Damages meaning, conscience, view of self and others Disrupted attachment – failed trust, failed relationships Problems with authority figures Difficulties resolving conflicts Inability to grieve Addiction to stress Resistance to change Deterioration, alienation Affective or Physiological Dysregulation • Impaired developmental achievement related to arousal regulation: Mood Bodily Functions Diminished awareness of emotional and behavioral states Difficulty describing emotional or bodily states Students who have experienced complex trauma• Developmentally adverse interpersonal trauma for over one year, and exposure was before the age of 18. • Subjective experiencing of: Rage Betrayal Shame Humiliation Interconnected Framework for School Mental Health Development of an Interconnected Systems Framework for School Mental Health February, 2012 Susan Barrett and Lucille Eber, National PBIS Center Partners; and Mark Weist, University of South Carolina University of Maryland, Center for School Mental Health) Trauma-Sensitive School PBIS Model Tier 1 Trauma-Sensitive School PBIS Model Tier 1 School policies, culture & climate Behavior management Instructional practices & approaches Modeling Classroom consultation TRAUMA SENSITIVE SCHOOL Trauma Proofing Curriculum Compassionate School Emotionally Safe School PFA-Psychological First Aid The Whole Learner Intellectual (Problem solving / creativity) Physical (Stamina) Emotional (Resiliency / empathy) All components are interdependent What’s “New” In The Context Of What’s “Old”? • A trauma-sensitive school environment is characterized by respect and supports capable of “taking over” when the student’s coping skills fail. – Operationalization • • • • • RtI PBIS Crisis/Disaster/Active Shooter Interventions Violence Prevention/Bullying Programs Character Education/Emotional Intelligence/Service Learning • Stress Management/Yoga • Restorative Discipline/Justice How We Become: Office of the Superintendant of Public Instruction State of Washington Ten Strategies of a Compassionate School 1. Focus on culture and climate in the school and community. 2. Train and support all staff regarding trauma and learning. 3. Encourage and sustain open and regular communication for all. 4. Develop a strengths based approach in working with students and peers. 5. Ensure discipline policies are both compassionate and effective (Restorative Practices). 6. Weave compassionate strategies into school improvement planning. 7. Provide tiered support for all students based on what they need. 8. Create flexible accommodations for diverse learners. 9. Provide access, voice, and ownership for staff, students and community. 10. Identify vulnerable students and outcomes and strategies Domains of Compassionate Instruction • Domain 1: Safety, Connection, and Assurance • Domain 2 : Emotional and Behavioral Self-Regulation • Domain 3: Competencies of Personal Agency, Social Skills, and Academic Skills The Six Principles 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) Always Empower, Never Dis-empower Provide Unconditional Positive Regard Maintain High Expectations Check Assumptions, Observe, Question Be a Relationship Coach Provide Opportunities for Helpful Participation Another Curriculum for Traumatized Children Connecting 1 Safety 2 Engaging 3 Trusting Processing 4 Managing the self 5 Managing feelings 6 Taking responsibility Adapting 7 Developing social awareness 8 Developing reflectivity 9 Developing reciprocity (Cairns, K. & Stanway, S., 2004.) Step I - Safety First Stay aware of the terror Provide and sustain a relaxing environment Use self appropriately to deal with a terrified student: voice, gestures, expression Use group work skills to create sense of safety Bring relaxation into the awareness of the child and encourage practice Discourage dependence on high stimulus activities • (Cairns, K. & Stanway, S., 2004.) Step II - Engaging Provide appropriate environmental stimulation for adults and students Learning about the effects of trauma is part of good classroom management Stories and metaphors are powerful tools for teaching about overwhelming events Encourage expression of experience and development of emotional intelligence Bring dissociation into awareness, develop sense of protector self and observer self Step III - Trusting and Feeling Accept the level of trust the student has to offer Encourage open discussion of issues of trust Encourage the student to express inner states in words, even though they will find this difficult Notice non-verbal signals of feelings and help student to recognize and name what is happening Identify self-transcending as well as self-assertive emotions Step IV - Managing the Self Discuss and practice relaxation and soothing activities with the student Avoid asking ‘why did you do that?’ Instead invite reflection linking inner state with actions Encourage the student to be interested in their own inner state with regard to their behavior Comment on small indicators of self-regulation Encourage students to build on growing capacity for self-management Procedures or Situations That May Trigger Prior Experiences of Trauma Include: Lack of controlpowerlessness Threat or use of physical force Observing threats, assaults, others engaged in self-harm Isolation Being in a locked room or space Physical restraints –or even wristbands Interacting with authority figures Interacting with men, in general Lack of privacy Removal of clothing –strip searches, medical exams Being touched –pat downs Being watched Loud noises Fear based on lack of information Darkness Intrusive or personal questions Step V - Managing Feelings Expect and contain disturbed behavior Encourage student to feel more in control space, time, activities Limit choices, restrict choice-making to less stressful situations and celebrate successes Encourage student to recognize and celebrate learning from mistakes Step VI - Taking Responsibility Recognize the power of traumatic identity and expect resistance to changing identity Provide choices about how they see themselves Allow student to let go of excessive or inappropriate responsibilities Encourage student to allow adults to be in control appropriately Celebrate any evidence of the student taking appropriate responsibility for behavior VII - Developing Social Awareness Encourage friendships and social interaction Identify and rehearse social situations requiring self-control in the student Encourage the student to broaden the range of their social connections and to be interested in people generally Promote activities motivating social accountability such as sport, drama, music VIII - Developing Reflectivity Promote self-esteem; catch them doing something good Provide and comment on role models of centered people who are comfortable in their own lives Encourage the use of tools for reflection such as keeping a diary Help students deal with feedback from a range of social situations Be creative about ways to help the student become fearlessly reflective IX - Developing Reciprocity • Provide and invite reflection on wide range of aesthetic experiences • Share thoughts and feelings • Apologize when we hurt the student • Encourage the student to reflect on our experience as well as their own • Invite the child to take our position - ‘What do you think I should do about this?’ in response to student’s behavior • Accept that we are a problem for the child Trauma-Sensitive School PBIS Model Tier 2 Tier 2 Trauma assessment screening DERS CPTSRI CANS CROPS/PROPS Sensory Regulation Experiential Therapies Group Trauma Interventions TARGET SPARCS SSET Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale (DERS) (Gratz, K.L.) • The DERS is a brief, 36-item, self-report questionnaire designed to assess multiple aspects of emotion dysregulation. • The measure yields a total score as well as scores on six scales derived through factor analysis: 1. Non-acceptance of emotional responses (NONACCEPTANCE) 2. Difficulties engaging in goal directed behavior (GOALS) 3. Impulse control difficulties (IMPULSE) 4. Lack of emotional awareness (AWARENESS) 5. Limited access to emotion regulation strategies (STRATEGIES) 6. Lack of emotional clarity (CLARITY) Nearly all empirically validated treatments for child trauma seek to make changes in the domain of emotion regulation, but there are few measures that assess this domain. Group Interventions • Support for Students Exposed to Trauma (SSET) Toolkit to manage stress and trauma: From National Child Traumatic Stress Network • Structured Psychotherapy for Adolescents Responding to Chronic Stress (SPARCS) – For traumatized adolescents continually living with ongoing stress – Six domains of functioning to cope more effectively, make better choices, and cultivate supportive relationships Goals: • to help traumatized adolescents make better choices for their lives • to cultivate healthier relationships • to activate meaning making • to rouse mindful action • to teach tools for coping with current and future stressors • to promote healing TARGET • Trauma Adaptive Recovery Group Education and Therapy (TARGET) • Objective: developed to help trauma survivors understand how trauma changes the body and brain’s normal stress response into a survival-oriented “alarm” reaction that can lead to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). • TARGET provides a practical skill-set that can be used by trauma survivors and family members to de-escalate and regulate extreme emotion states, to manage intrusive trauma memories, and to restore the capacity for information processing and autobiographical memory. • TARGET teaches a sequence of seven (7) skills described as the FREEDOM steps. • For ages 11-17 Trauma-Sensitive School PBIS Model Tier 3 Power and Control Strategies that are NOT Beneficial to a Traumatized Student • Threats • Bribes • Control over bodily functions, like prohibiting children from using the bathroom • Random enforcement of petty rules • Humiliation or degradation • Isolation • Corporal punishment Tier 3 Evidence-Based Trauma Interventions for Schools www.nctsn.org Individual Trauma Interventions TF-CBT CBITS (Child Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools Sensory ExperiencingSE ADBT-SP (Adapted Dialectical Behavioral Therapy) Life Skills/Life Story SITCAP http://www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/treatments-that-work/promising-practices Resources • Bluestein, J. (2001) Creating Emotionally Safe Schools: A guide for educators and parents. HCI • Cairns, K. & Stanway, S., Learn the child - helping looked after children to learn: A good practice guide for social workers, carers and teachers. London, England: BAAF • Coles, S. et al (2005) Helping Traumatized Children Learn: Supportive School Environments for Children Traumatized by Violence. Boston: Massachusetts Advocates for Children / The Hale and Dorr Legal Services Center of Harvard Law School • Craig, S. (2006) Reaching and Teaching Children Who Hurt: Strategies or your classroom. Paul Brookes Pub. • Hart, S. and V. Hodson (2004) The Compassionate Classroom: Relationship based teaching and Learning Puddledancer Press • Jaycox, L. et al.(2006) How Schools Can Help Students Recover from Traumatic Experiences: A Tool-Kit for Supporting Long-Term Recovery, RAND Corporation (TR-413), RAND Corp. • Jaycox, L. (2003) CBITS: Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools, Sopris West Resources cont. • Levine, P. (2007) Trauma Through A Child’s Eyes: Awakening the ordinary miracle of healing infancy to adolescence. Berkley, CA: North Atlantic Books • Levine, P. and M. Kline (2008) Trauma-Proofing Your Kids. Berkley, CA: North Atlantic Books. • Morrow, G. (1987) The Compassionate School: Educating abused and traumatized children. New York: Prentice-Hall. • Wolpow, R. et al. Compassionate Schools: The heart of Learning and Teaching. Seattle: Office of the Superintendant of Public Instruction State of Washington