Native Residential Schools

advertisement

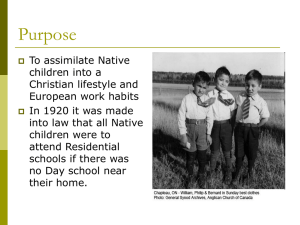

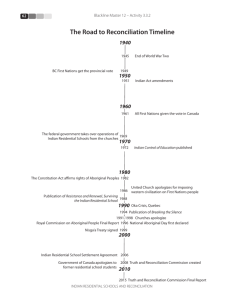

In 1883, Sir John A. MacDonald addressed the House of Commons and stated that “secular education is a good thing among white men, and if possible, good Christian men by applying proper moral restraints, and appealing to the instinct for worship that is found in all nations, whether civilized or uncivilized.” Prime Minister MacDonald argued that it was “of the greatest importance with a view to the future progress of the Indian race in the arts of civilization and in intelligence, that every effort should be made to educate and train the young Indian females, as well as the male members of the different Bands of Indians.” Ottawa favoured Native residential schools that ensured that the Native child would be dissociated from the prejudicial influences by which he is surrounded on the reserve of his band. At the peak of their existence, Native residential schools totalled 80 institutions, and perhaps only a minority of children; probably as many as 75 % of all eligible Innuit and status Indian children of school age. Native children were forcibly taken from their homes, or parents may have given them up willingly with promises of money and benefits, and by promoting the advantages for their children. Some parents were penalized or sent to jail if they did not send their children to the Residential Schools. “Native children were removed from their family homes and familiar lands. This isolation made children more vulnerable to the massive brainwashing that was undertaken to replace their pagan superstitions with Christianity, and their free and easy mode of life with relentless labour and routines.” “Clearly Canada chose to eliminate the Indians by assimilating them, unlike the Americans, who had long sought to exterminate them physically.” This “policy of assimilation, a policy designed to move Aboriginal communities from their savage state to that of civilization and then to make one community in Canada – a non-Aboriginal one.” Schools were operated by various religious groups including: Roman Catholics, Anglicans, United, Methodists, Baptists, and Jesuits. Despite this, the care of the Native children was anything but Christian. Food, the lack of it, and its bug-infested inferior quality, were on-going problems. Stealing became a real problem because the children were simply not getting enough to eat. Since dressing and grooming were considered indicators of the degree to which the assimilation program was succeeding, there were strong attempts to make the Native children look white by forbidding them to wear their Native costumes, and making them wear the European clothes. Often the children wore military-like outfits or school uniforms, often in poor repair. Natives reared in Residential Schools were “called apples: red on the outside, white on the inside, or they were called ‘wannabe Indians.’” The teachers were not well trained, did not have any cross-cultural training, did not know how to handle these children, were poorly paid, had poor working conditions, no time off, little privacy, and many had not even completed high school themselves. Native children while at the schools were not allowed to speak their Native language and if caught doing so, were badly beaten and abused. Children were also sent to bed hungry, and sent into isolation. “Yes, I received quite an education there all right, being to taught to feel guilty, inferior, and ashamed to be a ‘heathen’ and a ‘savage’. They beat me for speaking Ojibwa and for practising my own culture, and they crushed my spirituality with their religion.” There were many problems in the schools including … the sanitary conditions were horrid; poor ventilation; overcrowding in the homes; a high risk of fires because of the heating by stoves, and the use of coal-lit lamps; disease, illness, and death. “Children in these schools had been dying in unbelievable numbers.” Children were subjected to horrid treatment including various forms of abuse – verbal, physical, emotional and sexual. Native Residential Schools created children who had no family ties, were poorly educated, angry, and abused, and who had no experience in parenting. They also had no strong connections with their Native culture and language. Children were taken from a permissive Native culture, from parents and relatives who had never struck a child in their lives. The Residential School system was a supporter of corporal punishment. The “final irony of this situation was that in all areas of the country, except the high plains after the disappearance of the buffalo, children on entering the schools likely left behind a better diet, provided by communities that were still living on the land, than that which was provided to them by school authorities.” The survivors of the Indian Residential Schools system have, in many cases, continued to have their lives shaped by the experiences in these schools. Persons who attended these schools continue to struggle with their identity after years of being taught to hate themselves and their culture. The Residential Schools led to a disruption in the transference of parenting skills from one generation to the next. Without these skills, many survivors had difficulties in raising their own children. Native children learned that adults often exert power and control abuse. “Once all the witnesses are gone, maybe history can be re-written and this crime against Native humanity can be given a couple of good coats of whitewash/ But until then, I’m going to speak out because my body may be broken, but not my spirit. That is why, on spite of the government of Canada’s best and worst efforts, I can proudly say that I am still an Indian”, said Gabe Mentuck, a 77 year old Winnipeg resident, and survivor of a Native Residential School. Cruel Lessons AD0112 (1997) 25 minutes