Emotional well-being and trauma in youth

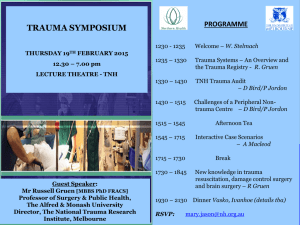

advertisement

Don’t Forget About Me !!!… Emotional well-being and trauma in youth Gregory E. Perkins, Ed.D.. MSW, ACSW, LAPSW Emotional well-being and trauma in youth Objectives • Discuss trauma in general • What is secondary trauma? • Secondary trauma within home settings • Secondary trauma specifically related to military families • Discuss methods to reduce secondary trauma for you “Traumatic experiences can be dehumanizing, shocking or terrifying, singular or multiple compounding events over time, and often include betrayal of a trusted person or institution and a loss of safety. Trauma can result from experiences of violence. Trauma includes physical, sexual and institutional abuse, neglect, intergenerational trauma, and disasters that induce powerlessness, fear, recurrent hopelessness, and a constant state of alert. Trauma impacts one's spirituality and relationships with self, others, communities and environment, often resulting in recurring feelings of shame, guilt, rage, isolation, and disconnection. Healing is possible.” The presentation seeks to educate the audience about the emotional health of children. Secondary trauma experienced by children may not have an immediate impact on daily functioning but potentially may provide significant emotional challenges later in life. According to the New York University Child Study Center “But beyond the sniffles and the bruised knees, there is a myriad of other aspects to Keeping Kids Healthy in today’s changing world. Parents and care-givers must navigate the complexities and challenges of issues ranging from self-esteem to substance abuse, from video games to eating disorders, from schoolyard bullying to campus violence.” Emotional well-being and trauma in youth Defining Trauma and Child Traumatic Stress Trauma Children and adolescents experience trauma under two different sets of circumstances. Some types of traumatic events involve (1) experiencing a serious injury to yourself or witnessing a serious injury to or the death of someone else, (2) facing imminent threats of serious injury or death to yourself or others, or (3) experiencing a violation of personal physical integrity. These experiences usually call forth overwhelming feelings of terror, horror, or helplessness. Because these events occur at a particular time and place and are usually short-lived, we refer to them as acute traumatic events. Emotional well-being and trauma in youth These kinds of traumatic events include the following: •School shootings •Gang-related violence in the community •Terrorist attacks •Natural disasters (for example, earthquakes, floods, or hurricanes) •Serious accidents (for example, car or motorcycle crashes) •Sudden or violent loss of a loved one •Physical or sexual assault (for example, being beaten, shot, or raped) In other cases, exposure to trauma can occur repeatedly over long periods of time. These experiences call forth a range of responses, including intense feelings of fear, loss of trust in others, decreased sense of personal safety, guilt, and shame. We call these kinds of trauma chronic traumatic situations. Emotional well-being and trauma in youth In other cases, exposure to trauma can occur repeatedly over long periods of time. These experiences call forth a range of responses, including intense feelings of fear, loss of trust in others, decreased sense of personal safety, guilt, and shame. We call these kinds of trauma chronic traumatic situations. These kinds of traumatic situations include the following: •Some forms of physical abuse •Long-standing sexual abuse •Domestic violence •Wars and other forms of political violence Emotional well-being and trauma in youth The 12 Core Concepts: Concepts for Understanding Traumatic Stress Responses in Children and Families Emotional well-being and trauma in youth 1. Traumatic experiences are inherently complex. 2. Trauma occurs within a broad context that includes children’s personal characteristics, life experiences, and current circumstances. 3. Traumatic events often generate secondary adversities, life changes, and distressing reminders in children’s daily lives. 4. Children can exhibit a wide range of reactions to trauma and loss. NCTSN Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma Task Force (2012). The 12 core concepts: Concepts for understanding traumatic stress responses in children and families. Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma. Los Angeles, CA, and Durham, NC: UCLA-Duke University National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. Emotional well-being and trauma in youth 5. Danger and safety are core concerns in the lives of traumatized children. systems. 6. Traumatic experiences affect the family and broader caregiving 7. Protective and promotive factors can reduce the adverse impact of trauma. NCTSN Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma Task Force (2012). The 12 core concepts: Concepts for understanding traumatic stress responses in children and families. Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma. Los Angeles, CA, and Durham, NC: UCLA-Duke University National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. Emotional well-being and trauma in youth 8. Trauma and post-trauma adversities can strongly influence development. 9. Developmental neurobiology underlies children’s reactions to traumatic experiences. 10. Culture is closely interwoven with traumatic experiences, response, and recovery. NCTSN Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma Task Force (2012). The 12 core concepts: Concepts for understanding traumatic stress responses in children and families. Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma. Los Angeles, CA, and Durham, NC: UCLA-Duke University National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. Emotional well-being and trauma in youth 11. Challenges to the social contract, including legal and ethical issues, affect trauma response and recovery. 12. Working with trauma-exposed children can evoke distress in providers that makes it more difficult for them to provide good care. NCTSN Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma Task Force (2012). The 12 core concepts: Concepts for understanding traumatic stress responses in children and families. Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma. Los Angeles, CA, and Durham, NC: UCLA-Duke University National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. Emotional well-being and trauma in youth Secondary Trauma Emotional well-being and trauma in youth Secondary Trauma Research also indicates that although most military children are healthy and resilient, and may even have positive outcomes as a result of certain deployment stressors, some groups are more at risk. Among those are young children; some boys; children with preexisting health and mental health problems; children whose parents serve in the National Guard, are reserve personnel, or have had multiple deployments; children who do not live close to military communities; children who live in places with limited resources; children in single-parent families with the parent deployed; and children in dual-military parent families with one or both parents deployed. Secondary Trauma A Child’s Signs of Stress Behaviors Moods Refuses to eat Listless Infants Ages < 1 yr Toddlers 1-3 yrs Cries, tantrums Irritable, sad Preschool 3-6 yrs Potty accidents, clingy Irritable, sad School Age 6-12 yrs Whines, body aches Irritable, sad Teenagers 12-18 yrs Isolates, uses drugs Anger, apathy Remedy Holding, nurturing Increased attention, holding, hugs Increased attention, holding, hugs Spend time together, maintain routines Patience, limitsetting, counseling Secondary Trauma EARLY CHILDHOOD TO ADOLESCENCE, 6–19 YEARS OLD Children and youth in these age ranges may have some of the same reactions to trauma as younger children. Often younger children want much more attention from parents or caregivers. They may stop doing their school work or chores at home. Some youth may feel helpless and guilty because they cannot take on adult roles as their family or the community responds to a trauma or disaster. Secondary Trauma • Children, 6–10 years old, may fear going to school and stop spending time with friends. They may have trouble paying attention and do poorly in school overall. Some may become aggressive for no clear reason. Or they may act younger than their age by asking to be fed or dressed by their parent or caregiver. Emotional well-being and trauma in youth Military families are not immune to the stresses of deployment. There is a growing body of research on the impact of prolonged deployment and trauma-related stress on military families, particularly spouses and children. Strengthening Our Military Families; Meeting America’s Commitment www.whitehouse.gov Secondary Trauma I serve too, I’m a military child, I stay strong when my dad goes away. If there is a war and my dad is detached, I will help him fight back. With my braveness and courage I can stay strong, My family’s support helps me carry on. Whenever we move, I start over again, I have to go to a new school, and make new friends. Even though people think I’m a military brat, I just don’t quite see it like that. My daddy helps defend our country, So we can live in peace and harmony. So all the military children help their mothers and fathers, Because we serve too, we’re their sons and daughters. By Kiara, 6th Grade, Belle Chasse Academy, Louisiana © 2003 Military Child Education Coalition www.militarychild.org DISCUSSION ?