KPA Media Workshop - Kenya Ports Authority

advertisement

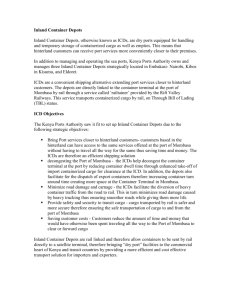

Growing prosperity through trade Kenya Ports Authority Media Workshop Port Efficiency and Hinterland Infrastructure A Symbiotic Relationship Overview Economic Geography • Ports do not exist in isolation. ‘However attractive a site1 may be for harbour development, it cannot create a port unless the situation2 allows the development of the all important relations with the hinterland’ • On the landward side they need to connect to areas of economic productivity (typically origin or destination ports ) • On the seaward side, their relationship to global sea-lanes and to other ports of significance (transshipment ports) 1. 2. The immediate area of land and waters in which facilities are developed The broad view of the port in the wider physical, human and especially economic environment *A geographical Study of the seaports of East Africa 1967 Overview Role of (Origin and Destination) Ports in the Transport Supply Chain • Provide for the balanced, smooth and cost effective flow of cargo through the port • Provide storage space required for intermodal change – mindful of different cargo carrying attributes. • Handle both: – – liner vessels operating on fixed routes to fixed schedules on fixed rates; and charter (tramp) vessels which operate entirely to the demands of the person hiring them. • Must cater for customs and other agency checks to ensure that goods arriving are legitimate, and that appropriate duties and fees are paid. Historic Development Although Ports on the East African Coast can trace the history back many centuries, their ‘modern’ development began with: • The opening of the Suez Canal • The construction of railways to exploit the economic hinterland • Tanga is the oldest of all the gateway ports on the East African seaboard, dating back to 1893, Mombasa 1895, Dar es Salaam 1905, Mtwara 1954 Historic Development Kasese Line (1956) Kampala Mainline (1931) Kisumu Line (1901) Mombasa-Nairobi Mainline (1896-1899) Mwanza Line (1928) Singida Line (1985) Arusha line (1929) Moshi -Voi Link-line (1924) Tanga- Moshi Mainline (1893-1911) Kalemie -Kabalo Line Tanga Link Line (1963) Mpanda Line (1949) Dar es SalaamKigoma Mainline (1905-1914) Kidatu Line (1965) TAZARA Mainline (1067mm Gauge) Dar es Salaam – Kapiri Mposhi (19701975) Historic Development Mombasa Established in 1895 to aid construction of the Uganda Railway 1947 – 1967: East African Railways and Harbours Corporation 1967 -1977: East African Harbours Corporation 1977 – 1986: Kenya Ports Authority and Kenya Cargo Handling Services 1986 - Present Day: Kenya Ports Authority Current Situation In 2011, of all volumes handled through Mombasa: • 72% of all port volumes for Kenya’s domestic market • 22% for Uganda • 2.3% for the DRC; 1.5% for Rwanda; Less than 1% for Tanzania, Burundi, South Sudan and Somalia 2% Kenya Imports 6% 20% Kenya Exports 60% 12% Uganda Imports Uganda Exports Remaining Transit Country Imports/Exports Throughputs Current Situation Major Imports: • Consumer Goods • Crude and Petroleum Products • Industrial Machinery • Vehicles • Iron & Steel • Plastics • Grains and Fertilizers • Other Dry Bulks Major Exports: • • • • Tea Coffee Cash Crops Soda Ash Current Situation • Kenya’s population concentrated in the central and western parts of the country; • Increasing coastal population Current Situation • Predominantly a Corridor Port – 80% (?) of goods transported at least 500km inland Current Hinterland Connectivity Current Hinterland Connectivity Challenges 1. Ship/Shore performance can be affected by yard congestion caused by slow clearing and forwarding arrangements World Average Container Terminal Comparison Description Units Small Medium Large All Mombasa Terminals Terminals Terminals Terminals Terminal Quay Line Capacity TEU per m of quay per annum 300 550 1300-1700 900 533 Gantry Crane Capacity TEU per crane per annum 45,000 80,000 130,000 100,000 79,902 Yard Capacity TEU per Hectare 7,500 14,500 35,000 20,000 23,000 Challenges 2. High dwell time necessitates additional infrastructure (to handle same volumes) Exports Empty Returns T'shipments Totals 109,941 115,303 242,927 19,927 770,804 5.4 8.5 11 11 15 Holding Capacity (c) 4,182 2,560 3,475 7,321 819 18,358 TGS Computation (d) 1,394 853 695 1,464 273 4,680 Peak Factor (e) 20% 20% 20% 20% 20% Total TGS Requirements 1,673 1,024 834 1,757 328 Annual Volume (a) Average Dwell Time(b) Domestic Imports Transit Imports 282,706 5,616 Challenges 3. Poor rail performance – in 2011 lifted less than 5% of port throughputs – Much of the rail network needs modification to take account of changing freight trends 4. High urban migration, poor urban planning and zoning – Planning across sectors required to achieve a balanced and smooth flow of cargo through the port 5. Poor urban road networks – All coastal traffic has to filter across Mombasa Island • Need northern and southern bypasses, extension of the duel carriageway between Nyali and Mtwapa – All transit traffic routes through the center of Nairobi, Kampala and other major towns Challenges Challenges Challenges 6. Capacity needed (ahead of demand) to cater for Trade/Transport Growth2 transport demand typically grows at double GDP Daily Freight Task Cargo Trade 2011 2015 Actual Containers (TEU/Day) 2020 2025 2030 Estimated 2,112 3,005 4,839 7,794 12,552 10,764 14,706 20,625 28,928 40,573 Conventional Cargo (Tons/Day) 4,025 5,056 6,766 9,054 12,117 Liquid Bulks (Tons/Day) 18,534 22,330 Dry Bulk (Tons/Day) - Challenges 7. Future cargoes will be carried on even bigger ships • Need Bigger and more specialized terminals and a concentration of port facilities Political Challenge • Devolution to County Governments (47) • Need integrated transport demand modeling ?