THEORIES of EXERCISE BEHAVIOR

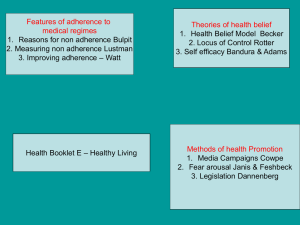

advertisement

Exercise Behavior and Adherence Session Outline Why Study Exercise Behavior? Why Exercise Behavior and Adherence Are Important Reasons to Exercise Reasons for Not Exercising The Problem of Exercise Adherence (continued) Session Outline Theories/Models of Exercise Behavior Determinants of Exercise Adherence Strategies for Enhancing Adherence to Exercise Settings for Exercise Interventions Guidelines for Improving Exercise Adherence Why Study Exercise Behavior? Despite the current societal emphasis on fitness, a small percentage of children and adults participate in regular physical activity. Why Exercise Behavior and Adherence Are Important 50% of adults are completely sedentary. 50% of youth (ages 12-21) do not participate in regular physical activity. 25% of children and adults report doing no physical activity. Only 15% of adults participate in vigorous and frequent activity. Only 10% of sedentary adults are likely to begin a program of regular exercise within a year. (continued) Why Exercise Behavior and Adherence Are Important Among boys and girls, physical activity declines steadily through adolescence. Physical inactivity is more prevalent among women, African-Americans, and Hispanics, as well as among older and less affluent adults. 50% of people starting an exercise program will drop out within six months. Daily attendance in physical education classes dropped from 42% to 25% between 1990 and 1995. Reasons to Exercise Weight control Reduced risk of cardiovascular disease Reduction in stress and depression Enjoyment Building self-esteem Socializing Reasons to Exercise KEY— Exercise combined with proper eating habits can help people lose weight; but weight loss should be slow and steady, occurring as changes in exercise and eating patterns take place. Reasons to Exercise KEY— Both the physiological and psychological benefits of exercise can be cited to help persuade sedentary people to initiate exercise. “Maintenance” as well as initiation of physical activity is critical. Reasons for Not Exercising Lack of time Lack of energy Lack of motivation Reasons for Not Exercising KEY— Exercise professionals should highlight the benefits of exercise and provide a supportive environment to involve sedentary people in physical activity. Reasons for Not Exercising KEY— People often cite time constraints for not exercising, but such constraints are more perceived than real and often reveal a person’s priorities. Individual Barriers to Physical Activity Lack of time, energy, or motivation Excessive cost Illness or injury Feeling uncomfortable Lack of skill Fear of injury (See table 18.1 on p. 403 of text.) The Problem of Exercise Adherence The Problem of Exercise Adherence Help those who start exercising to overcome barriers to continuing the exercise program. Help exercisers develop contingency plans to overcome factors leading to relapses (not exercising). Theories/Models of Exercise Behavior Health Belief Model (Becker and Maiman, 1975) The likelihood of exercising depends on the person’s perception of the severity of health risks and appraisal of the costs and benefits of taking action. Theories/Models of Exercise Behavior Health Belief Model KEY— Overall “inconsistent” support for Health Belief Model predictions of exercise behavior (Becker and Maiman, 1975) Theories/Models of Exercise Behavior Theory of Planned Behavior Exercise behavior is made up of intentions, subjective norms and attitudes, and perceptions of ability to perform behavior. (Ajzen and Madden, 1986) Normative beliefs and subjective norms Normative belief: an individual's perception about the particular behavior, which is influenced by the judgment of significant others (e.g., parents, spouse, friends, teachers. Subjective norm: an individual's perception of social normative pressures, or relevant others' beliefs that he or she should or should not perform such behavior. Theories/Models of Exercise Behavior Theory of Planned Behavior KEY— The theory of planned behavior is a useful theory for predicting exercise behavior. (Ajzen and Madden, 1986) Theories/Models of Exercise Behavior Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1986, 1997) Exercise behavior is influenced by both personal and environmental factors, particularly self-efficacy. What Is Cognition? Cognition is a term referring to the mental processes involved in gaining knowledge and comprehension, including thinking, knowing, remembering, judging and problem-solving. These are higher-level functions of the brain and encompass language, imagination, perception and planning. Theories/Models of Exercise Behavior Social Cognitive Theory KEY— Social cognitive theory has produced some of the most consistent results in predicting exercise behavior. (Bandura, 1986, 1997) Core Assumptions and Statements The social cognitive theory explains how people acquire and maintain certain behavioral patterns, while also providing the basis for intervention strategies (Bandura, 1997). Evaluating behavioral change depends on the factors environment, people and behavior. SCT provides a framework for designing, implementing and evaluating programs. Environment refers to the factors that can affect a person’s behavior. There are social and physical environments. Social environment include family members, friends and colleagues. Physical environment is the size of a room, the ambient temperature or the availability of certain foods. Environment and situation provide the framework for understanding behavior (Parraga, 1990). The situation refers to the cognitive or mental representations of the environment that may affect a person’s behavior. The situation is a person’s perception of the lace, time, physical features and activity (Glanz et al, 2002). The three factors environment, people and behavior are constantly influencing each other. Behavior is not simply the result of the environment and the person, just as the environment is not simply the result of the person and behavior (Glanz et al, 2002). The environment provides models for behavior. Observational learning occurs when a person watches the actions of another person and the reinforcements that the person receives (Bandura, 1997). The concept of behavior can be viewed in many ways. Behavioral capability means that if a person is to perform a behavior he must know what the behavior is and have the skills to perform it. Major Constructs in SCT and Implications for Intervention: • Environment: Factors physically external to the person; Provides opportunities and social support • Situation: Perception of the environment; Correct misperceptions and promote healthful forms • Behavioral capability: Knowledge and skill to perform a given behavior; Promote mastery learning through skills training • Expectations: Anticipatory outcomes of a behavior; Model positive outcomes of healthful behavior • Expectancies: The values that the person places on a given outcome, incentives; Present outcomes of change that have functional meaning • Self-control: Personal regulation of goaldirected behavior or performance; Provide opportunities for self-monitoring, goal setting, problem solving, and self-reward Major Constructs and Implications (continued) • Observational learning: Behavioral acquisition that occurs by watching the actions and outcomes of others’ behavior; Include credible role models of the targeted behavior • Reinforcements: Responses to a person’s behavior that increase or decrease the likelihood of reoccurrence; Promote self-initiated rewards and incentives • Self-efficacy: The person’s confidence in performing a particular behavior; Approach behavioral change in small steps to ensure success • Emotional coping responses: Strategies or tactics that are used by a person to deal with emotional stimuli; Provide training in problem solving and stress management • Reciprocal determinism: The dynamic interaction of the person, the behavior, and the environment in which the behavior is performed; Consider multiple avenues to behavioral change, including environmental, skill, and personal change. Theories/Models of Exercise Behavior Transtheoretical Model An individual progresses through five stages of change: 1. Precontemplation stage (does not exercise) 2. Contemplation stage (has fleeting thoughts of exercising) 3. Preparation stage (exercises, but not regularly enough) (Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross, 1992) (continued) Theories/Models of Exercise Behavior Transtheoretical Model An individual progresses through five stages of change: 4. Action stage (has been exercising regularly, but for less than six months) 5. Maintenance stage (has been exercising regularly for more than six months) (Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross, 1992) STAGE DETAILS Stage 1: Precontemplation (Not Ready) People at this stage do not intend to start the healthy behavior in the near future (within 6 months), and may be unaware of the need to change. People here learn more about healthy behavior: they are encouraged to think about the pros of changing their behavior and to feel emotions about the effects of their negative behavior on others. Precontemplators typically underestimate the pros of changing, overestimate the cons, and often are not aware of making such mistakes. These individuals are encouraged to become more mindful of their decision making and more conscious of the multiple benefits of changing an unhealthy behavior. Stage 2: Contemplation (Getting Ready) At this stage, participants are intending to start the healthy behavior within the next 6 months. While they are usually now more aware of the pros of changing, their cons are about equal to their Pros. This ambivalence about changing can cause them to keep putting off taking action. People here learn about the kind of person they could be if they changed their behavior and learn more from people who behave in healthy ways. They're encouraged to work at reducing the cons of changing their behavior. Stage 3: Preparation (Ready) People at this stage are ready to start taking action within the next 30 days. They take small steps that they believe can help them make the healthy behavior a part of their lives. For example, they tell their friends and family that they want to change their behavior. People in this stage are encouraged to seek support from friends they trust, tell people about their plan to change the way they act, and think about how they would feel if they behaved in a healthier way. Their number one concern is: when they act, will they fail? They learn that the better prepared they are, the more likely they are to keep progressing. STAGE 4: ACTION People at this stage have changed their behavior within the last 6 months and need to work hard to keep moving ahead. These participants need to learn how to strengthen their commitments to change and to fight urges to slip back. People in this stage are taught techniques for keeping up their commitments such as substituting activities related to the unhealthy behavior with positive ones, rewarding themselves for taking steps toward changing, and avoiding people and situations that tempt them to behave in unhealthy ways. STAGE 5: MAINTENANCE People at this stage changed their behavior more than 6 months ago. It is important for people in this stage to be aware of situations that may tempt them to slip back into doing the unhealthy behavior—particularly stressful situations. It is recommended that people in this stage seek support from and talk with people whom they trust, spend time with people who behave in healthy ways, and remember to engage in healthy activities to cope with stress instead of relying on unhealthy behavior. Theories/Models of Exercise Behavior Transtheoretical Model KEY— Different exercise behavior induction strategies are used during the different transtheoretical stages. (Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross, 1992) KEY— Matching the intervention to the stage of change is effective in producing high levels of regular exercise. Factors Associated With Participation in Supervised Exercise Programs Many factors, from demographics to physical and social environment, affect exercise participation. (See table 18.03 on p. 409 of text.) Determinants of Exercise Adherence: Highlights Demographic variables (e.g., education, income, gender, socioeconomic status) have a strong association with physical activity. Early involvement in sport and physical activity should be encouraged, because there is a positive relation between childhood exercise and adult physical activity patterns. Barriers to exercise are similar for white and nonwhite populations. (continued) Determinants of Exercise Adherence: Highlights Self-efficacy and self-motivation consistently predict physical activity. Spousal support is critical to enhance adherence rates for people in exercise programs. Spouses should be involved in orientation sessions or in parallel exercise programs. Exercise intensities should be kept at moderate levels to enhance the probability of long-term adherence to exercise programs. (continued) Determinants of Exercise Adherence: Highlights Group exercising generally produces higher levels of adherence than exercising alone, but tailoring programs to fit individuals and the constraints they feel can help them adhere to the program. Post-exercise participation predicts exercise behavior. (continued) Determinants of Exercise Adherence: Highlights Exercise leaders influence the success of an exercise program. They should be knowledgeable, give lots of feedback and praise, help participants set flexible goals, and show concern for safety and psychological comfort. A convenient location is an important predictor of exercise behavior. Strategies for Enhancing Adherence to Exercise Six categories of techniques Behavior modification approaches Reinforcement approaches Cognitive/behavioral approaches Decision-making approaches Social-support approaches Intrinsic approaches Category 1 Behavior Modification Approaches Prompts Verbal, physical, or symbolic cues that initiate behaviors (e.g., posters, running shoes by bed). Contracting Participants enter into a contract with their exercise leader. Category 2 Reinforcement Approaches Charting attendance and participation Rewards for Attendance and Participation Rewards improve attendance but must be provided throughout the length of the program. (continued) Category 2 Reinforcement Approaches Feedback Providing feedback to participants on their progress has positive motivational effects. Self-Monitoring Participants keep written records of their physical activity. Category 3 Cognitive/Behavioral Approaches Goal setting should be used to motivate individuals. Exercise-related goals should be self-set rather than instructor-set, flexible rather than fixed, and time based rather than distance based. Category 3 Cognitive/Behavioral Approaches Cognitive Techniques Dissociative strategies emphasize external distractions and produce significantly higher levels of exercise adherence than associative strategies focusing on internal body feedback. Category 4 Decision-Making Approaches Involve exercisers in decisions regarding program structure. Develop Balance Sheets Completing a decision balance sheet to increase awareness of the costs and benefits of participating in an exercise program can enhance exercise adherence. Category 4 A Decision Balance Sheet GAINS TO SELF LOSSES TO SELF Better physical condition Less time with hobbies More energy Weight loss (continued) Category 4 A Decision Balance Sheet GAINS TO IMPORTANT OTHERS LOSSES TO IMPORTANT OTHERS Get healthier so I can play baseball Less time with my family Become more attractive to my spouse Less time to devote to work (continued) Category 4 A Decision Balance Sheet APPROVAL OF OTHERS DISAPPROVAL OF OTHERS My children would like to see me be more active My boss thinks it takes time away from work My spouse would like me to lead healthier lifestyle (continued) Category 4 A Decision Balance Sheet SELF-APPROVAL SELF-DISAPPROVAL Feel more confident I look foolish exercising because I’m Improved self-concept out of shape (continued) Category 5 Social-Support Approaches Social Support An individual’s (e.g., spouse’s, family member’s, friend’s) favorable attitude toward another individual’s involvement in an exercise program. Social support can be enhanced by participation in a small group, the use of personalized feedback and the use of a buddy system. Category 6 Intrinsic Approaches Focus on the experience itself. Take a process orientation. Engage in purposeful and meaningful physical activity. Settings for Exercise Interventions Schools Work sites Home Community Health care facilities Settings for Exercise Interventions KEY— Community-based approaches appear to offer the best way of reaching large numbers of people. Guidelines for Improving Exercise Adherence Match the intervention to the participant’s stage of change. Provide cues for exercises (signs, posters, cartoons). Make the exercises enjoyable. Tailor the intensity, duration, and frequency of the exercises. (continued) Guidelines for Improving Exercise Adherence Promote exercising with a group or friend. Have participants sign a contract or statement of intent to comply with the exercise program. Offer a choice of activities. Provide rewards for attendance and participation. Give individualized feedback. (continued) Guidelines for Improving Exercise Adherence Find a convenient place for exercising. Have participants reward themselves for achieving certain goals. Encourage goals to be a self-set, flexible, and time based (rather than distance based). Remind participants to focus on environmental cues (not bodily cues) when exercising. (continued) Guidelines for Improving Exercise Adherence Use small-group discussions. Have participants complete a decision balance sheet before starting the exercise program. Obtain social support from the participant’s spouse, family members, and peers. Suggest keeping daily exercise logs. Help participants choose purposeful physical activity.