1. Introduction

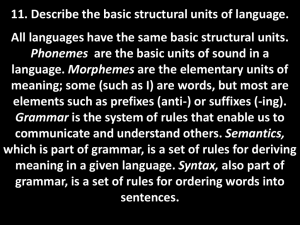

advertisement

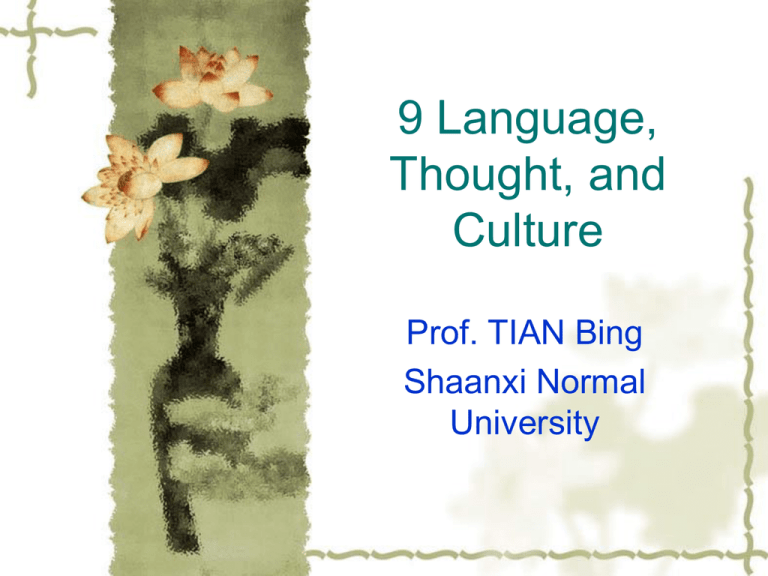

9 Language, Thought, and Culture Prof. TIAN Bing Shaanxi Normal University I. overvie w & history An Introduction IV. Methods and Testing Traditional Thoughts of Education Research M ethods Foreign Language Education Language Testing. (Pedagogical) Lexicography V. Learning II. Lg Description Language Descriptions Language Corpora. Stylistics. Discourse Analysis. vs CA Second Language Learning. Individual Differences in Second Language Learning. Social Influences on Language Learning. VI. Teaching III. Cognitive & Social Fashions in Language Teaching Language Acquisition: L1 vs L2 Language, Thought, and Culture. Language and Gender. Language and Politics. Language Teacher Education. World Englishes. The Practice of LSP Bilingual Education. M ethodology. Computer Assisted Language Learning Fig. 0 A Bird’s-Eye-Vie w of Applied Linguistic Studies 1. Introduction 9.1 Introduction 9.2 Language, Thought, and Culture and the 9.3 Re-Thinking Linguistic Relativity 9.4 Semiotic Relativity, or How the Use of a Symbolic System Affects Thought 9.5 Linguistic Relativity, or How Speakers of Different Languages Think Differently When Speaking 9.6 Discursive Relativity 9.7 Language Relativity in Applied Linguistic Research 9.8 Language Relativity in Educational Practice 9.9 The Danger of Stereotyping and Prejudice 9.10 Instead of Language-Thought-and-Culture: Speakers/Writers, Thinkers, and Members of Discourse Communities 9.11 Conclusion: The “Incorrigible Diversity” of Applied Linguistics 1. Introduction The hypothesis that language both expresses and creates categories of thought that are shared by members of a social group and that language is, in part, responsible for the attitudes and beliefs that constitute what we call “culture,” is a hypothesis that various disciplines have focused on in various ways. The field of applied linguistics, born in the fifties, at a time when the relation-ship of language and mind was the primary concern of formal linguistics, had a natural affinity to the brain sciences as they were developed then. Applied linguistics missed the heydays of empirical linguistics research that had led linguists like Boas, Sapir, and Whorf to investigate the relation of language and culture in preindustrialized societies. In the rationalist spirit of the fifties and sixties, and its information processing focus, the young field of applied linguistics was at first primarily interested in the sycholinguistic processes at work in language acquisition and testing, and in the cognitive dimensions of language pedagogy. In the eighties, the ascendancy of sociology and anthropology created a favorable climate for applied linguists to explore, in addition, the relation of language and social structure (Halliday, 1978), the social psychological aspects of language acquisition (e.g., Ellis, 1986) and the multiple discursive aspects of language in use in a variety of social contexts (e.g., Gumperz, 1982a & b; Ochs, 1988). It is not before the nineties, however, that advances in cognitive linguistics, linguistic anthropology, and the growing importance given to culture in language education brought a renewed interest in the relation of language, thought, and culture in applied linguistics. In this essay, I first review the canonical linguistic relativity hypothesis and its current resurgence in various fields related to applied linguistics. I then examine three major strands of thought in the triadic relation – language, thought, and culture – and how they are reflected in applied linguistics research. Finally, I explore the potential enrichment that the principle of language relativity can bring to applied linguistics, both in its theoretical endeavors and in its educational practice. 9.2 Language, Thought, and Culture and the Problem of Linguistic Relativity The relation of language, thought, and culture was first expressed in the early nineteenth century by the two German philosophers Johann Herder and Wilhelm von Humboldt, and picked up later by the American anthropologists Franz Boas, Edward Sapir, and Sapir’s student Benjamin Lee Whorf, in what has come to be called the linguistic relativity or Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. 9.2.1 Early precursors: Herder and von Humboldt If it be true that we . . . learn to think through words, then language is what defines and delineates the whole of human knowledge . . . In everyday life, it is clear that to think is almost nothing else but to speak. Every nation speaks . . . according to the way it thinks and thinks according to the way it speaks. (Herder, [1772] 1960, pp. 99–100, my translation) . . . there resides in every language a characteristic world-view . . . By the same act whereby [man] spins language out of himself, he spins himself into it, and every language draws about the people that possesses it a circle whence it is possible to exit only by stepping over at once into the circle of another one. (von Humboldt, [1836] 1988, p. 60) 9.2.2 The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis The best known formulation of the relation of language, thought, and culture is that captured by Sapir and Whorf under the term “linguistic relativity.” 9.3Re-Thinking Linguistic Relativity The strong version of linguistic relativity, or linguistic determinism, has been pretty much discarded, for a variety of convincing reasons. It is clear that translation is possible amongst languages, even though some meaning does get lost in translation, so the language web that Humboldt refers to does not seem to be spun as tightly as he suggests. Bi- or multilingual individuals are able to use their various languages in ways that are not dictated by the habits of any one speech community. And, with the increasing diversity of speakers within speech communities around the globe, it is increasingly difficult to maintain that all speakers of a language think the same way. A weak form of the hypothesis has remained generally accepted. But the idea that the grammar we use influences in some way the thoughts that we communicate to others did not affect the young field of applied linguistics at a time when rationalist, experimental, and, moreover, monolingual modes of research dominated all linguistic inquiry, and information processing theories of cognition dominated western psychology. The role of social context in language acquisition and use was a strong component of linguistic research, but western linguists were careful not to suggest in any way that the social context might influence the way people speak and think. A case in point is the debate between Basil Bernstein and William Labov. Bernstein had linked speakers’ different ways with words (i.e., elaborated vs. restricted codes) with the social class of these speakers (Bernstein, 1971). He suggested that middle-class speakers use more elaborated codes, i.e., assume less prior knowledge of their listeners, than working-class speakers, who assume greater shared knowledge on the part of their listeners, and thus use more restricted codes. Labov violently rejected Bernstein’s views, showing that poor black adolescents in New York’s inner city used as “elaborated” codes as Bernstein’s middle-class whites, thus dispelling the idea that social context conditions language use (Labov, 1972). However, since the late eighties, the notion of linguistic relativity has re-appeared in various, more sophisticated forms. In a recent state-of-the-art article on “Language and worldview” (1992), anthropologists Jane Hill and Bruce Mannheim argue that the hypothesis was never a hypothesis, but an axiom that was formulated at the time against “a naive and racist universalism in grammar, and an equally vulgar evolutionism in anthropology and history” (1992, p. 384). The resurgence of the concept in applied linguistics is due to a variety of developments in several related fields in the last 30 years. The first two come from work done in the twenties and thirties by Vygotsky and Bakhtin in the then Soviet Union. Vygotsky’s work, translated in the west in 1962 and 1978, became particularly influential in applied linguistics through the neoVygotskyian research of psychologist James Wertsch (1985) and linguist James Lantolf (2000). The work of Mikhail Bakhtin, discovered and translated in the west in the early eighties (1981, 1986), became influential in all areas of western intellectual life through the work of American literary scholars Michael Holquist (1990) and Gary Morson and Caryl Emerson (1990). Bakhtin’s thought has ushered in a period of postmodernism that questions the stable truths on which modern rationalism is based and gives a new meaning to the notion of linguistic relativity within a dialogic perspective. The other developments come from the emergence of new fields within the established disciplines of the social sciences. Innovative research in cognitive semantics (Lakoff, 1987, Lakoff & Johnson, 1980), cross-cultural semantics (Wierzbicka, 1992), cognitive linguistics (Slobin, 1996; Levinson, 1997; Turner, 1996; Fauconnier, 1985), and gesture and thought (McNeill, 1992) has provided new insights into the relation of language and thought. The social psychological study of talk and interaction as it is explored through discourse and conversation analysis (see Jaworski & Coupland, 1999; Moerman, 1988), discursive psychology (see Edwards & Potter, 1992), cultural psychology (Stigler, Shweder, & Herdt, 1990), and language socialization research (Schieffelin and Ochs, 1986; Jacoby & Ochs, 1995) has opened up new ways of relating thought and action. Advances in linguistic anthropology (e.g., Silverstein, 1976: Gumperz, 1982a and b; Friedrich, 1986; Hanks, 1996; Hymes, 1996; Becker, 2000) have placed discourse at the core of the nexus of language, thought, and culture. Finally, there is a growing body of research on bi- and multilingualism that counteracts the monolingual bias prevalent until now in applied linguistics (e.g., Romaine, 1995: Cook, 2000; Pavlenko, in press). This research is enabling us to consider the conceptual and cultural make-up of people who use more than one language in their daily lives (Pavlenko, 1999). Three edited volumes give the state of current research on the relation of language, thought, and culture: Duranti and Goodwin (1992), Gumperz and Levinson (1996), and Niemeier and Dirven (2000). In his introduction to this last volume, Lucy makes the distinction between three ways or levels in which language can be said to influence thought. The semiotic or cognitive level concerns the way any symbolic system (versus one confined to iconic-indexical elements) transforms thinking in certain ways. The linguistic or structural level concerns the way particular languages (e.g., Hopi vs. English) influence thinking about reality in particular ways, based on their unique morphosyntactic configurations of meaning. The functional or discursive level concerns the way in which using language in a particular manner (e.g., according to schooled, scientific, or professional “cultures”) influences thinking. Semiotic, linguistic, and discursive relativity interact in important ways. For example, semiotic effects are associated with cognitive patterns, that in turn are related to discourse regularities and cultural differences. I examine how these three levels of language relativity have been researched in recent years. 9.4 Semiotic Relativity, or How the Use of a Symbolic System Affects Thought From a phylogenetic perspective (the development of the human species), the argument has been made by biological anthropologist Terrence Deacon (1997) that the acquisition of symbolic reference, by contrast with iconic or indexical reference, represents a quantum leap in the development of humankind that has led to the development of uniquely human thought. It is this leap that animals have never been able to make. Using a Peircean terminology, Deacon argues that, whereas iconic reference (i.e., a relation of similarity) is based on the negation of the distinction between signs and their objects, and indexical reference (i.e., a relation of contiguity) is based on the associative links between iconic signs and their referents in the world, symbolic reference builds on both iconic and indexical signs, and adds the unique capacity of language as a semiotic system to reflect cognitively upon itself, i.e., to refer to itself as a symbolic system, and link sign to sign, word to word. Symbolic reference represents the core semiotic innovation that distinguishes the human “symbolic species” from other living species. Deacon argues that the ability to manipulate symbols is in a hierarchical relationship with the ability to manipulate iconic and indexical signs. Symbolic reference needs the two others, but goes beyond them, adding an interpretive response to the mere perception of icons and recognition of indexical links. What symbolic activity does is add sense, which is something in the mind, to reference, which is something in the world (Frege, 1879 in Deacon, 1997, p. 61). Taking the American psychologist James Mark Baldwin as his anchor point in the natural sciences, Deacon argues that the ability to use language symbolically has phylogenetically affected the human brain, not in a direct cause and effect manner, but indirectly through its effect on human behavior and on the changes that human behavior brings about in the environment. Even though the ability to use language as a symbolic system doesn’t bring about genetic changes in the nature of the brain, the changes in environmental conditions brought about by human symbolic responses to that environment can, in the long run, bias natural selection and alter the selection of cognitive predispositions that will be favored in the future. The tension between semiotic determinism and semiotic relativity underlies much of the work done by researchers in cognitive semantics like George Lakoff (1987) and Mark Johnson (1987). They remind us of the way in which language is both “in the mind” and also quintessentially embodied as the “bodily basis of meaning, imagination and reason” (Johnson, 1987). Johnson goes one step further than Vygotsky, to show that symbols have a way of changing not only our ability for abstraction and reason, but also our imagination and emotions (see also Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1991: and Shore, 1996). This is nowhere more apparent than in the linguistic “metaphors This is nowhere more apparent than in the linguistic “metaphors we live by,” i.e., those expressions that we take as representing reality “as it is,” but that are, in fact, mental representations or conceptual spaces (Fauconnier, 1985; Turner, 1996) that are constructed by language (Lakoff, 1987; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). They are so tied up with our bodily presence in the world that they can arouse emotions and passions, and lead people to action (see George Lakoff, 1992; Robin Lakoff, 1990, 2000). The metaphors given by Lakoff and Johnson 1980, for example, the mind is a container, are constructed by the language we use to talk about the mind, as in “it slipped my mind,” or “you must be out of your mind,” or in the phrase “comprehensible input.” They permeate the language of the media, the professions, the academic disciplines, and our daily conversations; they are often invisible to us because they are so ever present.