Program Evaluation and the Logic Model

advertisement

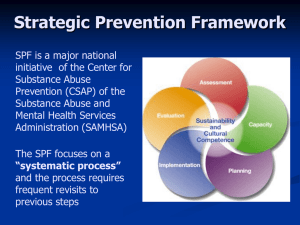

Program Evaluation, Research Design, and the Logic Model Research Methods for Public Administrators Dr. Gail Johnson Adapted, with additional material, by Dr. Mario Rivera for PADM 552, Designing Applied Research Multiple Methods—Mixed Methods Combination and Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Methods Neither is inherently better Realities of the situation rule Each work well in some situations, less well in others Arguably, all research is qualitative at its inception (choosing and defining the research question) and at its end (interpreting, evaluating findings); most program evaluations and other applied research involve multi-method triangulation (triangulation of both method and data) Quantitative and qualitative data collection often used together— mixed-methods approaches Available data with surveys Surveys with observations Pre-post data analysis (for instance, using t-tests) Surveys with focus groups 2 The Hypothesis Dilemma Hypotheses are designed to express relationships between or among variables. They are testable propositions that formally state theoretical expectations about these relationships among. If this is the nature of your topic or question, a hypothesis can add to your research. However, if your topic is more descriptive or explorative and analytical, generating a hypothesis may not be appropriate. A hypothesis may not be appropriate if: You have not identified and articulated a particular theoretical construct You do not have a set of defined variables. Your question turns on phenomenological description Your question entails an analytical review of the problem posed Your question involves in whole or part the study of a cultural group You will both engage in and research the program in question 3 What to Evaluate? Projects: a single intervention in one location or a single project implemented in several locations. Programs: an intervention comprised of various activities or projects which are intended to contribute to a common goal. Organizations: multiple intervention programs delivered by an organization. While seldom done, it is possible and sometimes desirable to evaluate an entire organization, or a complex of programs essentially defined by and defining an entire organization—e.g., the curriculum of a graduate program, its organizational core, without necessarily looking at all operational elements of the organization. When to Evaluate? Before program starts: To improve design During the implementation: To improve implementation Identify barriers to be removed Lessons learned about implementation To assess a critical element of a program under review, for instance a risk-management training component of an equal opportunity office in a public agency. When to Evaluate Mid-term evaluation Relevance, effectiveness, efficiency Lessons learned: management tool Impact evaluation (versus outcome evaluation) Either at the end of the project or a few years after the program has been operating: assessing a mature program Can also look at: effectiveness, efficiency, early signs of impact and sustainability Lessons learned for future projects or programs Distinction between short- and medium-term outcomes or results versus longer-term impacts. An impact is the net, long-term effect or complex of effects ensuing from a program. Gross impacts are affected by other causes, programs, secular changes (e.g., in attitudes toward smoking). If one can gauge gross impacts (the longer after the program the more the exogenous influences), can one isolate and evaluate net program impacts? Why Is Evaluation Useful? Feedback Accountability Learning Improvement Results Testing underlying assumptions or theory (change model or theory of change, action model or action theory) Funding decisions—publicizing and disseminating program results Evaluation Questions Compliance/ Accountability Questions Did the promised activities actually take place as they were planned? Implementation fidelity “How” Questions What Impact Questions Did was the sequence or processes that led to successful (or unsuccessful) outcomes the program achieve the desired results? What of positive but unplanned ones? Intended and unintended consequences Types of Evaluations Auditing: accounting for money Is the money being spent according to plan? Efficiency and effectiveness. Monitoring: measuring implementation and results Is the intervention producing the intended results? Process: measuring operations and service delivery Are there problems in service delivery? Types of Program Evaluations Feasibility evaluations Before the program begins Intended to improve program design Evaluability assessments Assesses potential usefulness of the evaluation Used to test out different strategies for conducting an evaluation What is doable given the situation? Evaluability Assessment Helps to define the actual objectives, implementation and management of a program. The actual objectives may differ from those initially planned. Determines the coherence of the program: are goals, activities, program infrastructure linked? Evaluability Assessment Key steps in the process: Interview key program staff to actual program mission, goals, objectives and activities. Site visits to observe and get a sense of what is going on. May include interviews with key stakeholders. Observe program delivery. Evaluability Assessment Reach agreement as to: Whether to conduct the evaluation. Scope and objectives of the evaluation. The decision could be to not conduct the evaluation. Evaluability Assessment: Challenges Key components of the program may not be well defined: Lack of agreement on program objectives. Lack clear, measurable indicators of performance and/or impact. Target group may not be clearly defined. The delivery system is poorly articulated. Types of Program Evaluations Formative evaluations During implementation Feedback about operations and processes Used to make mid-course corrections Definition: Performance Monitoring Performance monitoring: the continuous process of collecting and analyzing data to compare how well a project, program or policy is being implemented against expected results. Performance measurement tells you the what of what has occurred, while program evaluation explores the why. Program evaluation requires performance data but brings it to interpretive effort eventuating in judgments of value—evaluative decisions, or evaluation. Traditional vs. newer forms of assessment: Traditional focus on inputs, activities and outputs. Contemporary emphasis on if-then causal questions, incorporating change and action modeling. Types of Evaluation:Monitoring Ongoing review: On-time On-budget On-target Linked with ongoing management Measured against established baselines Indicators of progress toward targets Types of Program Evaluations Summative Evaluations At the end of the program or after the program has been running long enough to achieve its goals (with “mature” programs) Identify lessons learned Other issues: unintended outcomes, program sustainability, program efficiency, costs and benefits Sometimes called impact evaluations and ex-post evaluations Program Evaluation Summative Evaluation Question: Do Public Programs Work? Implied cause-effect relationship Did the program cause a desired outcome? Performance-based: Focus on outcomes, results, impacts, goal achievement. Differences Formative Evaluations Project Monitoring Best Suited to Early Years of Implementation Key Question: Are we doing things right? Have we hired the right people with the right skills? Have we marketed the program effectively? Have we met our strategic objectives? Have we spent our money according to our plan? Differences Summative Evaluations Measuring Results or Impacts A longer time before results or impacts are visible Key Question: Are we doing the right thing? This gets back to the theory or underlying assumptions of the program: We can do an excellent job at training people but if the problem derives from larger structural economic issues, a training program, no matter how well implemented, may show little result. Participatory Evaluation Responsibility for planning, implementing, evaluating and reporting is shared with all stakeholders. A partnership based on dialogue and negotiation. Participatory Participant focus and ownership Focus on learning Flexible design Rapid appraisal methods Outsiders are facilitators Traditional Donor focus and ownership Focus on accountability and judgment Predetermined design Formal methods Outsiders are evaluators Participatory Evaluation Participants: Engage in group discussions Conduct interviews Conduct field workshops Analyze data and develop conclusions Write the report Disseminate the evaluation results Participatory Evaluation How is it done? No single right way Commitment to the principles of participation and inclusion Core assumption: Those closest to the situation have valuable and necessary information Develop strategies to develop trust and honest communication Information sharing and decision-making Create even tables Participatory Evaluation Benefits: Increased credibility of results Results are more likely to be used Increased buy-in, less resistance Increased sustainability A tool for empowering the affected populations More flexibility in approaches Participatory Evaluation Challenges: Time consuming Clarifying roles, responsibilities and process Skilled facilitation Just-in time training No predetermined evaluation plan May be seen as less objective Participatory Evaluation Is it the right approach for you? Is there a need for: An independent outside judgment? Technical information? Will stakeholders want to participate? Is there sufficient agreement among the stakeholders so they can work together? Rapid Assessments Described as: “fairly-quick and fairly-clean” as opposed to “quick and dirty” or “long and clean” studies. Rapid Assessments Uses Diagnostic evaluations: processes, problems and causes of problems. Trouble-shooting: Why isn’t a program working as expected? What can be done to improve the program? Rapid Assessments Data Collection Observe: Converse: Record: Locate: Patterns, land use, behavior Talk with people, listen to their concerns and views; interviews, meetings. Write everything down. Existing data: reports, records, maps, prior studies. Principles of Rapid Assessments Process: Don’t rush when gathering information Probe and explore Listen rather than speak Be unimposing, open, non-judgmental Seek out the people most likely to be overlooked and find out what concerns them Rapid Assessments: No Fixed Definition Intended to do evaluations quickly while obtaining reasonably accurate and useful information Uses a systematic strategy to obtain just essential information Focus is on practical issues Sources: FAO.Org/docrep/ Principles of Rapid Assessments Optimize trade-offs: quantity, relevance, accuracy and timeliness. Planned but ability to pursue serendipity. Triangulation: use more than one technique and source of information. Face-to-face, on site learning. Learn with a general blueprint that is adapted as more information is obtained: use multiple methods, improvisation, cross-checking. Source: FAO.Org/docrep/. Rapid Assessments Is it the right approach for you? Important but no major decisions based on the study. Not controversial so face validity is sufficient. Limited time and resources available. Information is already available or requires in-depth understanding of process. Social Assessment Social assessment is a process that brings relevant social information into the decision-making process for program design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation. It assists in forming key outcome measures to be used in evaluation. Social Assessment Tools and Approaches include: Stakeholder analysis Gender analysis Participatory Rapid Appraisal Observation, interviews, focus groups Mapping, Analysis of Tasks, Wealth Ranking Workshops Objective-oriented Project Planning Working with Logic Models Visualize a program in context Systems approach, within an environment Identify the relationships between various components Identify cause and effect Identify key assumptions Models: Cause and Effect: Did the program cause something to happen? Education Employment Hierarchy of Objectives Reduced Poverty Sequencing Improved Quality of Life Increased Income Job Training Unemployed Logic Models The focus is on results or impacts rather than inputs and activities We are not training people just for the sake of training people We believe if we train the chronically unemployed, then there quality of life will be improved and poverty will decrease. Our goal is to reduce poverty Also called Program Outcome Model or Measuring for Results Remember, models are not reality; avoid reification. What makes a good model? Elements of the Logic Model Inputs: what resources are used University inputs: budget, number of faculty, number of staff, number of buildings, number of classrooms Activities: what the program does University activities: teaching, research, and service Elements of the Logic Model Outputs: the services or products produced University outputs: number of students that graduate, number of articles and books published by faculty Outcomes: what happened: immediate results Graduates are sought after, get good jobs, active alumni who donate big bucks Faculty well-known, obtain big grants, enhance rating of university Elements of the Logic Model Impacts: the “so what.” Larger, long term results, usually tied to program goals. A more informed and engaged citizenry, preserves democratic institutions, future leaders. Faculty research contributes to knowledge. Logic Model Logical Connections: Inputs to do activities Activities lead to outputs Outputs lead to one or more outcomes Outcomes lead to impacts Logic Model: Training Program Inputs Resources •money •staff •Supplies •mentors Activities Outputs Products •Training Programs •Dress for success coaching •Interview coaching •Resume assistance •Number of graduates per training session •% graduate rate Outcomes Benefits, changes •Increased skills •% Obtain jobs •% Obtain high paying, quality jobs •Increased self-esteem Impacts Goals •Increased income •Selfsufficiency •Family stability •Reduction in poverty Complex effects chain in partnered programs—network logic models Attribution difficulties; transparency & accountability challenges Partners 1, 2, 3, etc. Shared Common Outcomes Mario Rivera 47 Participatory evaluation Participatory evaluation is complex, requiring a correspondingly complex evaluative approach that can adequately deal with complex causality and interaction The case study is one approach to evaluation that can capture such complexity, through “thick description.” Mario Rivera 48 Logic Models The focus is on results or impacts rather than inputs and activities, although all of these are specified, along with indicators and measures. For example, you are in effect saying that We are not training people just for the sake of training people. We believe if we train the chronically unemployed, then they might gain meaningful and sustainable employment. Their quality of life will be improved thereby, and with enough such results from this and other efforts poverty will decrease. Our strategic goal is to help improve that quality of life and reduce poverty—these are the anticipated or hoped-for program impacts. Also called the Program Outcome Model, Measuring for Results, etc. Mario Rivera 49 Logic Models A logic model is a systematic and visual way to present and share your understanding of the relationships among the resources you have to operate your program, the activities you plan to undertake, and the changes or results you hope to achieve Provides stakeholders with road map describing the sequence of related events connecting the need for the planned program with the program’s desired results A program design and planning tool A program implementation tool as the core of a focused management plan Program evaluation and strategic reporting: presents program information and progress toward goals, telling the story of the program’s commitments and successes. Mario Rivera 50 Schematic Logic Model Impacts Outcomes Outputs Activities Inputs Mario Rivera 51 Logic Models and Planning Well established, easy-to-use tool for planning programs, eliciting and using stakeholder input. Provide a common language among managers, program or project principals, stakeholders including funders, and impacted communities. Graphic way to articulate—make explicit—and communicate program theory to internal and external audiences. Provides planners with a road map – asking them to determine where they want to end up (goals) and then chart their course of action. Logic modeling may help program managers in program planning as such, by bringing them to a fuller articulation of program goals and the connection among program aims, activities, and desired outcomes or impacts. Mario Rivera 52 Logic Model example—Preventive Health Ed. for an Immigrant Community POPULATION Characteristics; needs INPUTS Resources ACTIVITIES Strategies, services OUTPUTS program participation OUTCOMES desired changes in the population; impacts –Low –Program –Health –Number –Immigrant income, limited Englishspeaking community –Low use of health care coverage –Low use of preventive health services –Mostly employed in temporary and/or part-time positions –Community without an efficacious concept or custom of preventive health care in the way defined by the program (e.g., mammograms) and agency staffing, other resources –Funding –Existing curriculum and volunteer health educators –Prevention media –Verbal and written translation and interpreting resources care coverage review –Education about other available coverage –Prevention education sessions –Preventive health services in nontraditional locations –Focus groups –Regular tracking of health care coverage and preventive service use of new families signed up for coverage –Number of lapsed coverage renewed –Number attended education session about available resources –Number of contacts in nontraditional settings –Number of focus groups families will better understand the importance of preventive health services –Participating families will schedule and complete an increased number of well-child visits, cancer screening, prenatal checkups, etc. –Immunization rates will increase among children in the target population –The number of workdays or school days missed due to illness will decrease Another template: If-then sequencing Inputs Assumption or Needs or Underlying Condition Activities Immediate Outcomes Intermediate Outcomes Long Term Outcomes, Results, or Impacts Cascading Outcome-focused Logic Model Organizational-level Systemic Model •Human Capital •Technology Systemic model outputs and outcomes cascade down to next program level, for example, as inputs and resources or program context. Workforce Development Outcome Model Youth Development Outcome Model Financial Literacy Training Outcome Model Logic Model for the New Mexico SPF SIG The Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentive Grant (SPF SIG) is the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA) major demonstration project of their new Strategic Prevention Framework (SPF) and a Center for Substance Abuse Prevention’s (CSAP) flagship initiative. The SIG is a five-year cooperative agreement from CSAP to states. States receive up to $2.35 million per year for five years of which 85% must go to communities and 15% for State administration activities including a state-wide needs assessment and evaluation. The required components to the SPF SIG are as follows): Create a State epidemiological workgroup and state advisory board Have data-driven planning set state/local priorities Have a funding mechanism for targeting communities Address underage drinking in needs assessment, focus on prevention In 2005, New Mexico was in the first cohort of states to receive a SPF SIG grant. In FY 2006, the state began in local communities. New Mexico had five years of funding and an additional 6th year of an unfunded extension. National & State SPF SIG Goals—the overarching national goals are to: prevent onset and reduce progression of substance abuse, including underage drinking; reduce substance-related problems in communities; build prevention capacities and infrastructure at State and community levels SPF SIG New Mexico Community Logic Model Reducing alcohol-related youth traffic fatalities—change modeling SubstanceRelated Consequences Substance Use Underage BINGE DRINKING High rate of alcoholrelated crash mortality Among 15 to 24 year olds Underage DRINKING AND DRIVING Young Adult Intervening Variables Easy RETAIL ACCESS to Alcohol for youth Low ENFORCEMENT of alcohol laws Easy SOCIAL ACCESS to Alcohol Low PERCEIVED RISK of alcohol use Strategies (Examples) Enforce underage retail sales laws Social Event Monitoring and Enforcement Media Advocacy to Increase Community Concern about Underage Drinking BINGE DRINKING SOCIAL NORMS accepting and/or encouraging youth drinking Young Adult PROMOTION of alcohol use (advertising, movies, music, etc) Restrictions on alcohol advertising in youth markets Low or discount PRICING of alcohol Bans on alcohol price promotions and happy hours DRINKING AND DRIVING Multiplicity of Contextual and Causative Factors That Influence a Program’s Community Impact Multi-System, Cross-sector Collaboration Other Funding Grant Funding Inter-agency Community Partnership Project Outcomes Economy Community Impact Time Policy Changes Citizen Efforts Creative Commons This powerpoint is meant to be used and shared with attribution Please provide feedback If you make changes, please share freely and send me a copy of changes: Johnsong62@gmail.com Visit www.creativecommons.org for more information