The History of Low arousal approaches

advertisement

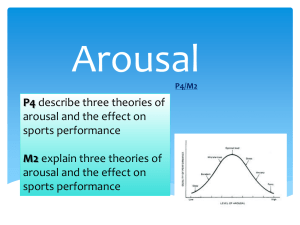

The History of Low arousal approaches Andrew McDonnell, PhD. Andy@studio3.org The Historical Context In the intellectual disabilities field the avoidance of punitive consequences has been a guiding principle of non aversive approaches especially so-called Positive Behavioural Supports (Carr et al, 1999). Verbal aggression appears to be a more common occurrence than physical aggressions in care environments (Kiely & Pankhurst, 1998). The Historical Context People with disabilities have been identified as a vulnerable group in terms of their exposure to restrictive practices (Chan et al, 2011) and physical restraint (Baker & Allen 2008). Whilst a technology of behaviour support and behaviour change was emerging. There was a paucity of data for behaviour management strategies (McDonnell, 2010). In the early 1990’s I became increasingly interested in both the academic rationale for training in the management of challenging behaviours and the reduction of restrictive practices in care environments. My Background I trained as a clinical psychologist in the UK (1986 to 1988). I worked both in institutional and community settings. I was trained in behavioural approaches. I became interested in how staff were trained to manage crisis situations. I also witnessed on many occasions ‘strong methods’ being used by care staff. Bad Practice The Term Low Arousal Approach The term low arousal approach was first used in 1994 (McDonnell, McEvoy & Dearden, 1994). The approach was then reformulated within a cognitive behavioural framework (McDonnell, 2010; McDonnell, Waters & Jones, 2002). The work was developed originally in institutional environments Key Areas of Interest There were three areas of early development. The first was a specialist high staff ratio support service for adults with intellectual disabilities and autism. The second area was a community service for people with intellectual disabilities. The third area was a hospital for people with intellectual disabilities and most notably a secure area for people with severe challenging behaviours. All three of these work areas involved the author working with people who presented with aggressive behaviours with varying levels of resources. Punitive Practices It was very noticeable that there was a great need to manage behaviours in a dignified and socially acceptable manner. The behaviour management approach was developed as a response to observational data that staff and carers often adopted punitive approaches in verbally managing aggressive behaviours. More Words of Caution “It is a mistake to think that once an intervention is underway, you no longer need to worry about serious outbursts and the necessity for crisis management” (Carr et al. 1994, p.14). Training Staff Between 1987 and 1992 I carried out staff training which what described as ‘non aversive behaviour management’ (low arousal began to be used in 1992). The majority of this training contained physical interventions with a simple behavioural rationale. The main emphasis was to show staff gentle physical interventions. Even in these early day no restraint ‘hold downs were taught and no techniques which involved the deliberate use of pain. Training Staff Based on these experiences and ongoing reviews of the literature, the author published a series of three brief articles for a practitioner journal in Intellectual disabilities (McDonnell Dearden & Richens, 1991a, 1991b, 1991c). The emphasis was on developing training systems. Training staff McDonnell et al. (1991b) described three principles involved in the training courses. They were: First, practitioners should avoid violent situations. The best way to avoid assault is to not be in the specific place. It is our experience that conflict can often occur in situations that tend to be repeated. Avoiding these predictable violent situations is a more practical option that managing them Second, where physical restraint is required it should not use procedures that involve painful locking of joints. The use of pain as means of coercion can damage the relationship between carer and service user. There is also the real possibility that a service user may consider retaliating in a similar manner. Third, staff should learn to use their body weight more effectively. These methods biomechanically require less physical strength to use, but more technical skill. Physical techniques that use bodyweight are more likely to be universally applied by male and female staff. The Development of Studio3 In 1992 the Studio3 organisation was initially formed. The aim was to allow independently the philosophy of low arousal to be developed. The name was chosen as it had no connotations with violence. ‘It sounded like a hairdressing salon!’ Social Validity Wolf (1978) argued that three dimensions were important in understanding the concept of social validity. First are goals or objectives ‘socially significant.’ That is, do they achieve what society wants? Second, are procedures or methods ‘socially appropriate’; literally do the ends justify the means? Finally, are consumers satisfied with the results? The Case for Socially Valid Behavioural Interventions I conducted several studies that examined the social validity of physical Interventions (McDonnell et al, 1993. McDonnell et al, 2000, Cunningham et al, 2002) Methods of intervention should be both effective and highly socially valid. The Views of Service Users There is a growing literature examining the views of service users. A survey of staff and service users in a secure facility found real differences between these groups. Staff reported the major reasons for use of restraint was to prevent harm. Service users tended to report that restraint was used as a form of punishment (Fish & Culshaw, 2005). Low Arousal Approaches: Early Speculations The early papers outlined five key principles. 1. Stay calm. Or more correctly give the appearance of being calm. Staff members need to control their breathing and avoid sudden movements and increases in the pitch of their voice. There is a commonly used phrase ‘do not pour fuel on an open fire’. In a conflict situation a staff member should be appear calm and not increase arousal in a conflict situation; especially when the service user they are managing is hyperaroused. Low Arousal Approaches: Early Speculations 2. Avoid physical contact. Human touch can have both calming and excitatory effects. When a service user is hyperaroused it is possible that physical contact may increase this further. Touch should be intermittent. Low Arousal Approaches: Early Speculations 3. Be aware of your own bodily reactions. It is the experience of the author that staff members in these situations are not aware that their own body language often communicates fear and distress. Individuals may perspire or stare at a service user (also physiologically arousing). Aggressive postures such as folding arms should be avoided. Low Arousal Approaches: Early Speculations 4. Keep your distance. Everyday social interactions tend to take place at a social distance of three to six feet. Research has demonstrated that close proximity to individuals who are angry or aroused may increase the likelihood of interpersonal violence. Low Arousal Approaches: Early Speculations 5. Respond in a non-violent manner. This is as much a moral as well as a pragmatic approach. Essential to the approach is the view that violent acts elicit violent responses, thus creating behavioural response chains that increase the likelihood of violence. Developing Low Arousal Approaches There was a consistent emphasis on the role of staff behaviour in the maintenance of challenging behaviours. In 2002 the low arousal approach was reformulated within a CBT framework. A key facet was an understanding of staff attributions surrounding challenging behaviours (including belief systems). Staff Perceptions “peoples’ levels of motivation, affective states and actions are based on what they believe, than in what is objectively true” (Bandura, 1997, p21). Staff who work with aggressive service users face a challenging and sometimes dangerous task. They all come into their job with their own learning history of managing aggressive behaviour and conflict resolution McDonnell, 2010). A Service Example (Circa 2000) We conducted a four year audit of a service where staff were trained in low arousal approaches. 18 services users were monitored over this period. All of these individuals were judged to present with significant challenges. Organisational monitoring All incidents of PI were actively monitored by staff. Where multiple incidents occurred in a month a review meeting to discuss PI reduction strategies was held which involved a clinical psychologist. Low arousal strategies were reviewed in these meetings and written reactive plans were produced. Measures Staff reported Management of aggression forms. These had to be filled in after any use of PI in the service. Reliability of reports were established by getting staff to separately rate a sample of the same incidents for a one month period incidents (this produced reliabilities of over 96%). Service user support plans were audited for evidence of ‘low arousal approaches’. Figure 1: The use of the ‘chair method’ of physical intervention used . over four years Figure 2: The use of the walking method over the four year period Low arousal strategies Key Main Findings There appeared to be significant reductions in PI usage across the service. There was a shift from more intrusive (chair restraint) PI’s to less intrusive methods (walk around method). The increased use of low arousal strategies is a measure based on a ‘paper trail’ as opposed to directly observable evidence. The Last 10 Years A greater emphasis in the Studio3 system on low arousal approaches. Training in the last several years has spread to several European countries. There has been an increasing emphasis in placing these approaches within a stress management framework. The Last 10 Years (Research) ‘In summary, what do we know about the effectiveness of physical interventions training? At present, a worldwide training industry is based primarily on anecdotal evidence and fourteen studies only four of which show reasonable design quality. An evidenced based approach represents the only way forward.’ (McDonnell, 2008)