Non aversive approaches

Developing Crisis Support Plans Using Low Arousal

Approaches..

Andy McDonnell, PhD,

Director, Studio3 Training Systems,

WWW.studio3.org

Challenging Behaviour

A definition

‘Culturally abnormal behaviour of such intensity, frequency or duration that the physical safety of the person or others is likely to be placed in serious jeopardy, or behaviour that is likely to seriously limit the use of, or result in the person being denied access to ordinary community facilities.’

Emerson 1995

Non aversive approaches

Early behavioural interventions concentrated on the consequences of behaviour.

The use of punishing consequences to suppress behaviour has been extremely controversial.

In many ways we attempt to control what we fear.

In the last two decades there has been an increasing emphasis on intervening before a challenging behaviour occurs.

Many of these approaches can be labelled as positive behavioural supports.

Autism

People with autistic spectrum disorders

(ASD) can present behaviours that challenge and a recent survey of the behavioural intervention literature identified a diagnosis of autism as a risk marker for physical aggression

(McClintock, Hall and Oliver, 2003).

Aggression

These behaviours may furthermore result in injury to clients when attempts are made to restrain them and thus may provoke physical abuse from carers

(Rusch, Hall & Griffin, 1986).

Crisis Management is Important

Carr et al.

(1994) maintained that crisis interventions are needed and that “it is a mistake to think that once an intervention is underway, you no longer need to worry about serious outbursts and the necessity for crisis management” (Carr et al.

1994, p.14).

Crisis management Research is

Needed!

A large number of behavioural intervention studies have tended to focus on long term interventions for physical aggression (Horner, Carr, Strain, Todd and Reed, 2000) with short term management receiving less attention

(McDonnell, 2006).

Aggressive Behaviour:

Often emerges in early childhood and persists over decades.

Is functional and adaptive

Is about communication and control

Causes of violence and aggression in persons with an

ASD

Communication difficulties

Confusion

Unexpected change – breaking a routine or ritual

Environmental factors – heat, overcrowding, noise, etc.

Sensory differences i.e. hyper and hyposensitivity

Pain or medical problems

Medication changes

Inactivity/boredom

Demands and requests

Emotional problems and mental illness

Too many rules and restrictions

Being denied a need or getting something that they don’t want

PEOPLE!!

Cognitive Behavioural

Approaches

THOUGHTS

FEELINGS

BEHAVIOUR

Testing Our Assumptions about

Behaviour

Aware Not Aware

In Control

Not in

Control

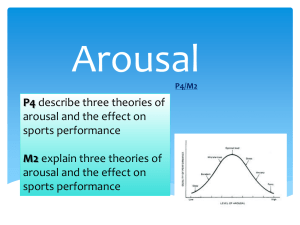

What is arousal?

Arousal is a construct which is notoriously difficult to define with researchers adopting views that it is either a unitary or multifaceted construct; recent research in neurobiology indicates that there is a generalised arousal mechanism in the brain which feeds cortical functions (Pfaff, 2006).

Negative effects of high arousal

The construct of arousal is considered useful in understanding the regulation of emotion (Pfaff, 2005) and arousal and stress are considered to be important in the moderation of emotions (Reich and

Zautra, 2002).

Arousal and ASD

There is some laboratory evidence of differences in physiological responses of individuals with ASD compared to non autistic controls (Althaus, van Roon,

Mulder, Mulder, Aarnoudse and

Minderaa 2004; Hirstein Iversen and

Ramachandran 2001; van Engeland,

Roelofs, Verbaten and Slangen, 1991)

Sensory difficulties in ASD

Increasing interest in this area.

‘some autistic individuals cannot tolerate food of some particular taste, smell, texture and appearance (certain colours for example) or even the sound it produces when they chew it’

(Bogdashina, 2003, p63).

Sensory difficulties are vital to understand if staff are to develop behaviour management strategies.

Sensory difficulties

Processing using one modality.

Inconsistency in visual perception.

Sensory agnosia (difficulties interpreting a sense).

Delayed processing.

Sensory overload: Remember this can be a painful physical experience for some people.

Maintaining Equilibrium: A central tenet.

A balance between internal and external stimuli is required to maintain levels of arousal.

Equilibrium/balance

The human body has a sensitive self-monitoring and self-regulating system that is constantly working to maintain the body in homeostasis (balance).

I would suggest that physiological arousal employs a similar mechanism. A balance is struck between internal and external sources of arousal. Let us call it arousal homeostasis.

Each individual has an optimum performance threshold of arousal to functioning successfully.

We are aiming for a state of arousal equilibrium .

Regulation of arousal is problematic for some people with ASD.

Maintaining equilibrium

Stereotyped movements may help maintain equilibrium because they serve a de-arousing function.

Rituals may occur more frequently when arousal levels increase.

People avoid specific arousing stimuli.

Other do individuals seek out arousing stimuli.

Arousal and Stress

Stress and anxiety have been proposed as factors in challenging behaviours of people with ASD (Howlin, 1998; Groden, Cautela,

Prince and Berryman, 1994). Lazarus and

Folkman (1984) described a transactional model of stress emphasizing interaction between an individual and his/her environment. Stress occurs when the demands of stressors outweigh coping responses and there is a clear interaction between environmental and physiological events.

Aggressive behaviour and panic reactions

Many people with ASD and challenging behaviours show signs of panic in specific situations.

Behaviours may be interpreted as deliberate by carers in these situations

Similarities have been drawn between the symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder and some individuals who present with challenging behaviours (Pitonyak,

2004).

Panic reactions can often lead to people needing to escape from situations.

Panic responses do not appear to habituate rapidly.

This may be true of a specific subset of people with

ASD.

Low arousal approaches in practice

A key component of these approaches to behaviour management is REFLECTIVE

PRACTICE.

A carer may often be making a situation worse accidentally

What makes you angry?

How do you express your anger?

How do you cope?

How do you Destress?

Definition

" attempts to alter staff behaviour by avoiding confrontational situations and seeking the least line of resistance."

(McDonnell, Reeves, Johnson & Lane,

1998, p164)

Low Arousal

Theoretical Assumptions

ASSUMPTION ONE

Most people who are challenging are usually extremely aroused at the time. We should therefore avoid doing anything that will arouse a person who is already upset.

ASSUMPTION TWO

A large proportion of challenging behaviours are usually preceded by demands and requests, therefore reducing these should help to reduce the frequency and perhaps the intensity of the incidents.

ASSUMPTION THREE

Most communication is predominantly non-verbal, therefore we should be aware of the signals we communicate to people who are upset.

Symptoms of physiological arousal

In anxiety disorders arousal is increased in response to a ‘perceived threat’.

Rapid beating heart.

Sweaty hands and other forms of perspiration.

Pupils may increase in size.

Panic reactions (including escape from situations).

Anatomy of an Incident

CRISIS

Arousal

Level Triggering Phase

‘Normal’ range

Time

Non verbal behaviours

Eye contact: Should be avoided when a person is angry.

Touch: Keep this to a minimum.

Interpersonal space: We are much more aware of the space around us when we are angry or aroused.

Postures: Threatening postures need to be avoided.

Non verbal behaviours

Language: language needs to be clear and simple, avoid ritualistic debates.

Avoid key trigger phrases such as ‘calm down’

Do attempt to appear calm and give off a minimal amount of energy.

Developing a crisis plan

John is a 23 year old man with intellectual disabilities and autism.

His repetative questioning of staff was considered to be a major problem.

John was reported to be really dangerous.

Verbally aggressive behaviours occurred on a daily basis.

Physical aggression at least weekly.

An Observation

Analysis

Staff member is ignoring the person.

John is very stressed.

His arousal level is so high that cannot process what the staff member is saying to him.

He is asking ‘Who is on later’ and not getting the answer he NEEDS to hear.

Individualised training

The staff team had a one day training course which focussed on low arousal approaches.

John’s support plan was reviewed.

Many staff felt that John ‘did things on purpose.

We made them understand that he was frightened and scared.

Individualised Training

We selected practical examples of everyday situations that led to physical aggression.

Strategies to distract John (tea and coffee worked well).

Visual aids used

Staff practiced a new approach using role play methods.

After training

Outcomes

There was no incidents of physical aggression for 6 months.

Staff reported that John seemed a lot calmer.

Staff reported that they felt calmer.

One staff member felt that things had worked but they were ‘Giving In’.

Longer term arousal regulation

Relaxation techniques.

Sensory environments.

Physical exercise.

Sensory diets.

Environmental design.

Antecedent control.

Conclusions

Sensitivity to arousal as a model of working has several implications.

We are aiming to create ‘ arousal equilibrium ’ for individuals.

Assessment of individual arousal sensitivity should be a fundamental part of the approach.

Pharmacological approaches may need to concentrate more on reducing or in some cases increasing physiological arousal.

Conclusions

Designing environments where arousal levels can be controlled (heat, light, colour, space, sounds).

Developing more self control distraction strategies (wearing walkmans, use of mood music).

Anxiety reduction strategies may help some individuals (see Attwood, 2006).

Consider individual arousal responses when developing individualised activity plans.

Conclusions

The behaviour of staff has significant impact on the management of challenging behaviours.

Staff may inadvertently trigger challenging behaviours (McDonnell, 2005)

Training staff/families to recognise the initial signs of panic and sensitivity may have a significant effect.

Short term demand reduction should be a major facet of crisis management for people with ASD/Intellectual disabilities.