Demographic, Economic and Social Predictors of Psychological

advertisement

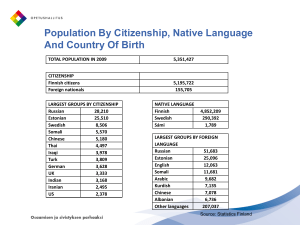

Demographic, Economic and Social Predictors of Psychological and Sociocultural Adaptation of Immigrant Youth Colleen Ward and Jaimee Stuart Centre for Applied Cross-Cultural Research Victoria University of Wellington Psychological Aspects of Immigration • Acculturation • Integration • Adaptation – Psychological – Sociocultural This Study • Objective: To predict psychological and sociocultural adaptation in immigrant youth • From individual-level data (e.g., gender, perceived discrimination) from the International Comparative Study of Ethno-cultural Youth (ICSEY) and nationallevel data archival data from the World Bank (e.g., GDP) and the International Social Survey (e.g., attitudes toward immigrants) • By using Multi-level Modelling International Comparative Study of Ethno-cultural Youth (ICSEY) • Key Questions – How do immigrant youth adapt in their societies of settlement? – How well do they adapt? – What is the relationship between how immigrant youth adapt and how well they adapt? • Survey Methods – Demographic variables – Intercultural variables – Adaptation variables International Comparative Study of Ethno-cultural Youth • Participants – 5366 immigrant youth – 2631 national youth – In Europe: Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, United Kingdom; North America: Canada, United States; Australasia: Australia, New Zealand; and Israel Variables of Interest: Individual Level • Positive and Negative Indicators of Adaptation – Psychological: Life satisfaction (α =.78), Psychological Symptoms (α =.83) – Sociocultural: School Adjustment (α =.68), Behavioural Problems (α =.81) • Level 1 – Personal background: Age, gender, generation – Perceived discrimination (α =.84) Variables of Interest: National Level • Per capita GDP in $US ($28,504- $84,508) • % Immigrants (4%- 39%) • Positive Attitudes – The government should help minorities to preserve traditions. – Immigrants are generally good for the economy. – Immigrants make societies open to new ideas and cultures. • Negative Attitudes – Immigrants increase the crime rate. – Immigrants take away jobs from those born in this country – People who do not share traditions cannot be fully [ ]. SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS Country N Age % Sec Gen % female Per Discr P.C. GDP % Imm + Att - Att Australia 456 15.22 51.1 60.5 1.97 42,131 16 3.16 3.03 Canada 257 15.87 44.7 55.6 2.00 46,236 21 3.12 3.00 Finland 442 15.30 9.0 50.0 2.20 44,512 4 2.94 3.36 France 517 15.61 82.6 57.3 1.90 39,460 10 2.53 3.15 Germany 295 16.36 58.3 52.2 1.90 40,152 13 2.72 3.50 Israel 456 16.31 1.1 41.0 2.50 28,504 39 3.24 3.13 Netherlands 351 14.87 66.7 49.7 1.92 46,915 11 2.60 3.27 N.Z. 243 15.71 65.1 54.4 2.47 29,352 22 2.92 3.11 Norway 484 15.24 46.1 52.2 2.10 84,538 10 2.56 3.45 Portugal 426 14.79 53.1 62.0 2.17 21,505 9 3.17 3.24 Sweden 829 15.11 57.4 51.0 1.82 48,936 14 2.95 3.09 U.K. 120 15.18 89.2 45.0 2.21 36,144 10 2.48 3.42 U.S. 472 14.60 44.7 60.6 2.09 47,199 14 2.90 3.09 Total 5365 15.35 49.1 53.3 2.07 Hypotheses • At the individual level, perceived discrimination will predict poorer adaptive outcomes • At the country level – Greater immigrant density (larger numbers of immigrants) and more negative attitudes toward them predict poorer adaptive outcomes, – Positive attitudes toward immigrants predict better adaptive outcomes, and – Higher per capita GDP predicts greater life satisfaction Hypotheses • There will be an interaction between immigrant density and perceived discrimination with the negative effects of perceived discrimination on adaptation exacerbated under more immigrantdense conditions. PREDICTORS OF ADAPTATION IN IMMIGRANT YOUTH Psych Probs Life Sat Beh Probs Sch Adj 2.236** 3.622** 1.753** 3.843** Per capita GDP -.001† .000 -.000 .000 % of immigrants .016** -.021** .016** -.000 Positive Attitudes .144 -.087 -.047 -.267 Negative Attitudes .314 -1.025** .709* -.515* Age .015 -.010 -.013 -.041** Gender .152* -.105** -.208** .102** Generation -.003 -.053 -.077* -.000 Perceived Discrimination (PD) .318** -.228** .172** -.239** .005** -.001 .008** -.002 Intercept Level-2 Level-1 Cross-level Interaction PD x % of immigrants ** p <.01, * p <.05, † p <.10 Psychological Problems: Cross-level Interaction between Perceived Discrimination and % of Immigrants 1.83 MIGRANT = -6.677 Psychological Problems MIGRANT = 5.423 1.70 1.57 1.43 1.30 -0.96 -0.46 0.04 Discrimination 0.54 1.04 Behavioural Problems: Cross-level Interaction between Perceived Discrimination and % of Immigrants 2.77 MIGRANT = -6.677 Behaviour Problems MIGRANT = 5.423 2.56 2.36 2.15 1.94 -0.96 -0.46 0.04 Discrimination 0.54 1.04 Summary of Key Findings • Personal background factors are associated with psychological and sociocultural adaptation • Perceived discrimination predicts negative adaptation outcomes • % of immigrants and negative attitudes toward them exert significant negative effects on adaptation in immigrant youth • Perceived discrimination exerts more negative influence on adaptation problems under immigrant dense conditions Obviously, the integration strategy can be pursued only in societies that are explicitly multicultural, in which certain psychological preconditions are established... These preconditions are the widespread acceptance of the value to a society of cultural diversity (i.e., the presence of a multicultural ideology), and of low levels of prejudice and discrimination; positive mutual attitudes among ethnocultural groups (i.e., no specific intergroup hatreds); and a sense of attachment to, or identification with, the larger society by all individuals and groups (Berry, 2001). But there are questions….. • Positive and negative: Why is it only negative attitudes that affect adaptation? Policy Implications • Maximising the benefits and minimizing the risks of immigration – Restrict numbers? – Improve attitudes, intergroup relations and social cohesion? – Whose responsibility? To “get the best out of immigrants” and to reap the benefits of diversity, diminishing (or even better eliminating) negative attitudes toward immigrants should be a fundamental objective. Ensuring fair and equitable access to participation and discouraging separation from the mainstream society are also important. In the end, our findings support the contention that it is not only the responsibility of immigrants to “fit in” and adapt to their new homelands, but it is the responsibility of the receiving society to ensure a receptive environment that is conducive to mutually beneficial goals. For further information contact: Colleen.Ward@vuw.ac.nz