Evidence-_Crispin_Passmore_December-2013x

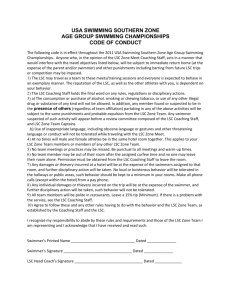

advertisement

Crispin Passmore Evidence to the Low Commission 5 December 2012 My evidence • • • • • • • The evidence, analysis and opinion offered here is a personal reflection, based upon my personal experience working in delivery of legal services since 1993. I started out as a volunteer in a Citizens Advice Bureau and have been employed as an adviser, specialising in representing consumers at tribunals. I became first Chief Executive of Coventry Law Centre, perhaps largest Law Centre in UK at time. I subsequently worked for Legal Services Commission for five years, most latterly as Interim Executive Director for Policy and Strategy Director In 2009 I became Strategy Director at Legal Services Board, which is responsible for modernising legal regulation in order to deliver a reformed and competitive legal market focused on consumers. None of the views expressed should be attributed to current or former employers. For the record, the Legal Services Board has never, and would not, take a stand on what Government policy or expenditure on legal aid should be. However, the LSB is able to comment on consumer need, and the extent to which market is becoming flexible in response to need. Summary • Legal aid – Cost – Innovation – Provider and consumer voices • Understanding consumers – They are not homogenous – Even the most vulnerable are often resourceful • Access to Justice – Access to justice or access to lawyers? – Spatial access to lawyers – Technological impacts • Developing a strategy for access to justice – Subsidising production – Lowering costs – Liberalisation How well has legal aid delivered? Legal aid: too expensive? • Most expensive in world – 2008 = £38.60 per head. Country 2006 Legal aid spending per capita (£) England & Wales Scotland Norway Netherlands New Zealand* Sweden Ireland Australia Canada* Germany France Spain £0.00 £37.74 £31.49 £21.76 £14.17 £11.17 £11.08 £10.07 £9.00 £8.84 £4.57 £3.22 £2.55 £5.00 £10.00 £15.00 £20.00 £25.00 £30.00 £35.00 £40.00 International Comparison of Publicly Funded Legal Services & Justice Systems, University of York, http://www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/statistics/mojstats/international-legal-aid-comparisons.pdf Legal aid: How much money would be enough? • “Optimal effectiveness in the context of a given substantive law could be expressed as complete equality of arms – the assurance that the ultimate result depends only on the relative legal merits of the opposing positions, unrelated to the differences which are extraneous to legal strength and yet as a practical matter affect the assertion and vindication of legal right. This perfect equality of course is utopian as we have already implied; the differences between the two parties can never be completely eradicated. The question is how far to push toward the utopian goal and at what cost”. • (M CAPPELLETTI et al, Access to Justice Volume 1, Part one – General report 1979) Legal aid: lack of innovation • Legal aid decisions focus on budget management made in the absence of ‘consumer voice’ – – – – Providers sought to speak on ‘behalf of vulnerable consumers’ Tangled own and consumers interests Contractual terms became more rigid Reduced scope for genuine innovation e.g. CLS Direct effective competition to CAB helpline – Further complexity adding to consumer confusion • LSC forced to tackle quality issues because of lack of initiative/ credible assurance from sector – “There is no quality problem here” – Quality Mark – ‘costly’ burden imposed by LSC Legal aid: misaligned incentives (Eligibility test, NfPs and competition) • Example of vested interest: – – – – NfPs general aim to serve everyone LSC funding came with eligibility test Contracts provide for a casework and have target hours (inputs) Casework had to be specialist – therefore elevated status compared to other caseworkers – Incentive to spend as long as necessary with single client, not deliver services to as many clients as possible – Incentives to characterise cases as complex • Consequences: LSC identified NfP providers as costly and inefficient – Undermined value of services provided – Increase in audit activity, increasing costs to LSC and providers Consumers are not homogenous advice seeking robots Consumers respond differently to legal needs: (http://research.legalservicesboard.org.uk/news/data-sources/ ) Consumers respond differently to legal needs: Knowledge & Psychology • “Action taken depends on characterisation of a problem as legal Overall, whereas respondents said they would seek help from a lawyer in relation to 44% of problems characterised as legal, the same was true of only 11% of problems not characterised as such. For example, when problems concerning home ownership were not characterised as legal, just 11% of respondents suggested lawyers as a source of help. This rose to 55% when problems were characterised as legal”. • Civil Justice in England and Wales: Report of the 2007 English and Welsh Civil and Social Justice Survey, LSRC,2008 Consumers respond differently to legal needs: Cost and perception • Response to civil and social justice problems shows that: “after taking account of problem type, for problem types where legal aid is most available, people eligible for legal aid are significantly more likely to use lawyers than those on low incomes, but not eligible for legal aid” 12 Income, Lawyers and Access to Justice Factsheet, LSRC 2011 Consumers respond differently to legal needs: Making a choice to handle alone (http://research.legalservicesboard.org.uk/news/data-sources/ ) Access to justice? Define your terms: Access to Justice means providing consumer choice • Research into cost and court procedures • That individual consumers do not use legal representation because they do not believe they need to. – Statistically significant relationship between legal representation and age, work pattern and socio-economic group. – Those with legal representation are more likely to be women, aged 2544, work (full or part-time) and be from socio-economic groups C2DE. – Those without legal representation are more likely to be men, aged 65+, have a household income of more than £45,000 and be more certain that their case will have a positive outcome. • What's cost got to do with it? The impact of changing court fees on users, Ministry of Justice 2007 Access to legal services: Importance of the advice sector • The role of this sector in providing access to legal services is important to understand. As one piece of research points out: the specific use of lawyers in the U.K. surveys is roughly the same as in the U.S. - 27% in England and Wales, 29% in Scotland versus 26% in the U.S. Where the substantial difference emerges is in the use of other third-parties. Moreover, because non-lawyers in the U.K. are authorized to give legal advice (such as volunteer-staffed Citizens Advice Bureaux or proprietary legal advice centres), the effective difference is even greater: Americans received advice from those who are able to give legal advice in only 37% of cases, compared to 60-65% of U.K. cases. Furthermore, a far smaller percentage of the U.K. respondents, as compared to U.S. respondents, “lumped” their problem by doing nothing at all: fewer than 5% versus 29%. • Higher Demand, Lower Supply? A Comparative Assessment of the Legal Landscape for Ordinary Americans, Gillian K. Hadfield 2010 Access to legal services: Choosing a provider - what consumers say – 2011: When they did need to access legal services, many participants said there had been an absence of choice in legal provider or a dearth of information to support the decision-making process. Due to limited financial resources, time pressures and a desire to remain local, individual and SME business participants felt their choices were restricted. As a consequence, there was a high incidence of participants relying on recommendations from friends, family or business contacts – 2010: In addition to personal recommendation, next most important factor in choosing was logistical reasons – either because of its proximity to their home or work because it was the closest, because its local to us, or because the advice centre had convenient opening times – 2009: A few respondents have complained about the opening hours of services. For example a client with an employment law problem complained that solicitors and NfP agencies only opened during office hours and he could not get time off work to attend an appointment. Other clients complained that due to their disabilities they could not attend open door services to queue and because agencies did not answer their phones they were unable to make an appointment to see someone. – 2004: 25% had gone to an advice source, waited too long to be seen and given up. 23% felt an advice source had inappropriate opening hours. 15% were put off because an advice source did not provide appointments. However, 18% were put off because an appointment was provided too far in the future. 14% felt an advice source was too intimidating. ...Only 10% considered an advice source was too far to travel to. Developing measures of consumer outcomes for legal services, Opinion Leader research, 2011 Exploring One-Stop Shop Legal Service Delivery in Community Legal Advice Centres LSRC 2010 Availability of advice survey: the findings Legal Action Group 2009 The Advice Needs of Lone Parents, Richard Moorhead, Mark Sefton and Gillian Douglas Cardiff University 2004 Access to legal services: Geography • Most organisations serve a wide geographical area Findings from the Legal Advice Sector Workforce Surveys, Legal Services Research Centre 2007 Access to legal services: Technology Access to legal services: Technology • “There certainly needs to be a repositioning of internet-based advice. It is entirely logical for advice to be digital by default – the mantra of the UK government in relation to its own services. Those giving advice on legal services should aim to provide it self-sufficiently on the net with the express aim, as in The Netherlands, that people will self-represent. There are certain implications just from that. It will be difficult to maintain charges for information so that there should be overt acceptance that information is being provided for all and for free. Then further support should be provided as necessary. The first line of support should be through skype or telephone to someone physically present but not in the room. Advisers in offices should be the second line of support. That requires a considerable retooling by the advice and law centre sector.” • Roger Smith – Internet Advice worthy but dull? 2012 http://lawyerwatch.wordpress.com/2012/03/20/internet-legal-adviceworthy-but-dull-guest-post/ What is the role of the state in meeting legal need? What is the role of the state in meeting legal need: Subsidise production • Subsidise services so they are accessible: “Lawyers are charged with the task of assisting individuals in making use of the law and enforcing their rights, but violations of those new rights often generate claims of a small economic value, so that lawyers as a rule cannot economically handle them. The basic challenge is to provide machinery to make those rights effective” (Cappelletti 1978) • Subsidies risk protecting inefficient firms increasing overall costs • Legal aid paid by inputs not outputs has been a subsidy What is the role of the state in meeting legal need: Subsidise production – “Access to justice through legal aid is not an unlimited free good. Legal services procured through legal aid are delivered with finite resources which need to be managed within the government’s three year spending regime and judged alongside other priority areas, such as health and education. The challenge is to ensure access to justice within available resources, and to make the best possible use of the budget so that it supports the aims of the justice system”. • Lord Carters Review of Legal Aid Procurement 2006, http://www.lawcentres.org.uk/uploads/Legal_Aid_A_marketbased_approach_to_reform_Summary.pdf What is the role of the state in meeting legal need: Reduce costs • Access to Justice has five waves: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Legal aid – funding for individuals for legal advice and representation before the courts, with legal aid funding provided for over two million consumers in 2011/12. Public interest law - E.g. Equalities & Human Rights Commission, taking legal action against those who discriminate on behalf of society as whole, or Citizens Advice campaigning on behalf of consumers. Informal justice such as alternative dispute resolution Competition policy – used to ensure markets operate effectively minimising the occurrence of legal disputes, through organisations like the Office of Fair Trading and the Competition Commission. Requiring organisations to create access to justice mechanisms for their customers, employees, and other stakeholders – E.g consumer dispute resolution services such as eBay. • All focus on making disputes cheaper/quicker to resolve • Cheaper system = greater access What is the role of the state in meeting legal need: Regulation • Access to legal services and issues of quality: • “In demotic language, markets where one can expect to be mugged tend to deter participation, even though muggers may be in a small minority. Alternatively, it can be noted that although markets for ‘pigs in pokes’ may have existed in economic history, the sizes of those markets were highly limited. In such circumstances, and as the market for lemons example shows, lack of confidence in the market may depress the prices that can be achieved for high quality supplies, as well as reducing the demand for legal services overall” • (Understanding the economic rationale for legal services regulation, Regulatory Policy Institute 2010) What is the role of the state in meeting legal need: Regulation • Consumers are at risk of market failure from information asymmetries • Reputation is vital in the absence of other information – but individual consumers are infrequent users of services • “Ideally what is wanted are arrangements that can effectively reduce the risks of consumers receiving a lower quality service than they had reasonably expected, without imposing unduly large information costs on suppliers or customers”. (Understanding the economic rationale for legal services regulation, Regulatory Policy Institute 2010) • Lack of information best addressed through competition not prescription by vested interests What is the role of the state in meeting legal need: Regulation • Liberalisation to make market work effectively for consumers • Legal services is a market with many segments (A framework to monitor the legal services sector- Oxera 2011) • “The LSB’s priority would be to ensure legal services become more affordable (and so accessible), whilst ensuring consumer confidence in the quality of legal services. In public policy terms, the idea is win-win: consumer trust and affordability can both increase the size of legal service markets. It is also reasonably clear in its trajectory, being deregulatory in approach: the case for regulation has to be made with evidence not the other way round. The central idea is that regulators need to be sure that the markets the govern stimulate competition on quality rather than just price” (Moorhead 2011) What role can Alternative Business Structures play in providing social welfare law advice: • ABS impacts the theory: • “legal services become more affordable (and so accessible), whilst ensuring consumer confidence in the quality of legal services. In public policy terms, the idea is win-win: consumer trust and affordability can both increase the size of legal service markets”. (Legal Services and the market for lemons - Moorhead 2010) • “There is a large fragmented market of series of markets with identifiable over capacity and inefficiency. The reserved, unregulated consumer services will probably be most attractive ..... though the £2bn legal aid market could also be tempting. Capital could be made available for investment in expansion or IT consolidation. There are economies of scale to be derived from investment in and the restructuring of commoditised or bulk services. They are in a position to expend and exploit their brands in ways in which the fragmented high street is not” (After Clementi -The impending legal landscape, Mayson 2006) Finally, some challenges... 1. Be radical and forward looking 2. Recognise and challenge existing vested interests 3. Don't start with service design – start with consumer need 4. Don’t prescribe answers – create an environment where legal providers innovate and compete for consumers by driving value (quality, price, access) 5. Help consumers choose and use legal services – so that they punish poor delivery and reward excellence 6. Let consumers voices rule – no paternalism 7. Use evidence not anecdote Further information sources the Low Commission may wish to consider Quality of legal services • For a summary of available information see LSB research webpages: http://research.legalservicesboard.org.uk/analysis/demand/quality-of-advice/ • For an assessment of how quality can be considered from a consumer perspective: Quality in Legal Services, Chapter 3 What constitutes quality for consumers http://www.legalservicesconsumerpanel.org.uk/publications/research_and_rep orts/documents/VanillaResearch_ConsumerResearch_QualityinLegalServices.pdf • For issues with traditional legal services ‘quality marks’: Voluntary quality schemes in legal services • http://www.legalservicesconsumerpanel.org.uk/ourwork/quality_assurance/do cuments/FinalReport_VQS.pdf • For an views on how quality might be regulated in legal services: Approaches to Quality • http://www.legalservicesboard.org.uk/news_publications/latest_news/pdf/201 20913_summary_responses_recd_lsb_response_approaches_quality_final.pdf Spatial distribution of need/demand for social welfare law advice • For a summary of available information see LSB research webpages: http://research.legalservicesboard.org.uk/analysis/supply/static-marketanalysis/distribution-of-services/ • Data on geographical supply of legal services : Data Platform 2010 http://research.legalservicesboard.org.uk/news/data-sources/ • Request to the Legal Services Commission: Indicative Spend data relating to Social Welfare Law (SWL) and Family procurement areas”, Legal Services Commission, 2009 (No longer on their website) • 2009 perspective on SWL and legal aid: • http://www.ilagnet.org/jscripts/tiny_mce/plugins/filemanager/files/Wellingt on_2009/Powerpoints/Community_legal_services_-_CP.pdf