Technical Guide to HIV

Prevention, Treatment and

Care for People Who Use

Stimulants

CDARI Press

March 2014

Dr Marcus Day, Director

Take Home Messages

• Not all stimulant use is associated with HIV

• Incidence is critical Vulnerability to HIV is

heightened in certain contexts when in high

incidence environments stimulant use involves

concomitant sexual behaviours creating HIV

“blossoms”

• Certain subgroups are at heightened vulnerability

for the sexual transmission of HIV

• Drug treatment is NOT effective in reducing HIV .

Take Home Messages

• immuno-depressiveness of crack and

cocaine

• Efficacy of ART despite immunodepressiveness

• Prohibition and criminalisation compound

the vulnerability

• This technical guide fully embraces

existing strategies and guidelines of the

Joint United Nations Programme on

HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the United Nations

Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and

the World Health Organization (WHO)

regarding HIV prevention, treatment and

care for all persons, including for people

who use drugs ].

[1],[2],[3

•

•

•

•

[1] Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, Getting to Zero: 2011-2015 Strategy — Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

(UNAIDS) (Geneva, 2010). Available from

www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2010/JC2034_UNAIDS_Strategy_en.pdf

[2] WHO, UNODC, UNAIDS Technical Guide for Countries to Set Targets for Universal Access to HIV Prevention, Treatment and Care for

Injecting Drug Users (Geneva, World Health Organization, 2009). Available from www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/idu_target_setting_guide.pdf

[3] WHO, UNODC, UNAIDS Technical Guide for Countries to Set Targets for Universal Access to HIV Prevention, Treatment and Care for

Injecting Drug Users – 2012 Revision (Geneva, World Health Organization, 2012). Available from

http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77969/1/9789241504379_eng.pdf

World Drug Report 2012 (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.12.XI.1). Available from http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-andanalysis/WDR-2012.html

Intended Use

• This Guide is intended for use by all

stakeholders, service providers,

policymakers and agencies at the local,

national or regional levels, who undertake

to have a positive impact on HIV

prevention, treatment and care among

stimulant users.

Purpose of this Guide

• The purpose of this guide is to facilitate

access to HIV prevention, treatment and

care for people who use stimulants

• The Guide describes how evidence-based

and recommended interventions may be

helpful to people who use stimulants as a

group whose primary risk of HIV

transmission is through sexual behaviours

correlated to their stimulant use.

This Technical Guide provides:

• A package of core health interventions for

people who use stimulants, whose route of use

is primarily through non-injecting means.

• A framework and process for setting targets

• A non exhaustive set of recommended indicators

and targets (or “benchmarks”) for setting

programme objectives and monitoring and

evaluating outcomes of core health interventions

for stimulant users

• Examples of data sources

Operational Definition

• People who use stimulants include:

– individuals who use cocaine,

– various forms of smokeable cocaine base,

commonly referred to as crack cocaine,

– paste or pasta base, paco, basuco:

– amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS)

– or any of the other varieties of psycho

stimulant drugs.

Variability of Stimulant Use

• wide range of variability in levels of

stimulant use, from minimal to occasional

to regular/daily use.

Range of Responses

• People who use stimulant drugs differ in

their range of responses:

• experience may vary from little or no

consequences to various levels of

distress,

• Responses often compounded by other

physical, mental or external factors that

are exacerbated by use in a criminalised

environment.

A comprehensive package of

efficacious interventions for HIV

prevention, treatment and care

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

HIV testing and counselling

Antiretroviral therapy (ART)

Needle and syringe programmes for people who inject

stimulants

Harm reduction services targeting stimulant use.

Condom programmes for people who use stimulants and

for their sexual partners

Screening, prevention and treatment of STIs, hepatitis B,

hepatitis C, and tuberculosis (TB)

Behavioural interventions aimed at reducing HIV

transmission

Targeted information, education and communication

programmes

Overlap between stimulant use and

HIV

Factors determining the overlap between

stimulant use and HIV transmission

include three dimensions that require

consideration :

• the type of stimulant used;

• the way in which it is used and;

• contexts in which that use occurs.

Types of stimulant drugs used

•

•

•

•

crack, cocaine,

methamphetamine,

ecstasy or other psychostimulants):

HIV transmission risks vary by the type of

drugs used and by whether risk

behaviours occur in proximity to a

localised HIV epidemic particularly one

with an elevated incidence

Route of administration

• Stimulants are most commonly used via

non-injection methods such as

– oral,

– smoked,

– snorted,

– inserted anally

• Injected

Frequency of use

• Short-acting stimulants like crack or

powder cocaine are administered

frequently

• Longer-acting stimulants such as

amphetamine or methamphetamine tend

to be used less frequently.

Crucial variables

• Immediacy, duration and magnitude of the

stimulants effect

• frequency and quantity of the stimulant

used[1].

• Vulnerability to HIV is heightened in

certain contexts when stimulant use

involves concomitant sexual behaviours.

[1] Hatsukami DK, Fischman MW., 1996 Crack cocaine and cocaine

hydrochloride. Are the differences myth or reality? JAMA 1996 Nov

20; 276(19):1580-8

Unique subgroups & HIV

• Some subgroups are at heightened vulnerability

for the sexual transmission of HIV:,

• the homeless and other and street engaged

populations,

• those with untreated, co-occurring psychiatric

issues,

• men who have sex with men, sex workers,

• street youth,

• itinerant migrant labourers are examples of

these subgroups.

Barriers to access

• Local environmental factors (social,

cultural, religious, economic, political)

impact on and may create barriers to

access to HIV prevention, treatment and

care

• Requiring a sensitive, competent and

sustained response in an environment

where accessibility and utilisation of

services are a key indicator of success.

Cocaine

• Smoking cocaine correlates with HIV and

other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

such as syphilis

[1].[2],[3],[4].

•

•

•

•

[1] R. Marx and others, “Crack, sex, and STD”, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, vol. 18,

No. 2 (1991), pp. 92-101

[2] M. L. Williams and others, “An assessment of the risks of syphilis and HIV infection

among a sample of not-in-treatment drug users in Houston, Texas”, AIDS Care, vol. 8,

No. 6 (1996), pp. 671-682

[3] M. W. Ross and others, “Sexual behaviour, STDs and drug use in a crack house

population”, International Journal of STD and AIDS, vol. 10, No. 4 (1999), pp. 224-230

[4] M. L. Williams and others, “Determinants of condom use among African Americans

who smoke crack cocaine”, Culture, Health and Sexuality, vol. 2, No. 1 (2000), pp. 1532

Increased libidinous urges

• Certain sub populations of male and

female cocaine and crack users report an

increased libidinous urge, corresponding

with high numbers of reported sexual

partners and episodic unprotected sex[1].

[1] M. W. Ross and others, “Sexual risk behaviours and STIs in drug abuse treatment populations whose drug of choice

is crack cocaine”, International Journal of STD and AIDS, vol. 13, No. 11 (2002), pp. 769-774

Desire, disinhibition,acquisition,

• The desire to acquire smokable cocaine

triggers disinhibition and, as such, it is

often found in the context of sexual

behaviours such as the exchange of sex

for drugs or money.

Immuno-depressiveness

• There are indications of the immunodepressiveness of crack and cocaine and

that its use may impede the mechanisms

that inhibit viral uptake and may enhance

viral progression.

Accelerates HIV progression

• There is evidence that cocaine and crack

use accelerates HIV disease progression,

Research conducted among women living

with HIV[1], although there is no reason to

believe that men are not similarity affected

though the mechanism for this is still

unclear.

[

1] J. A. Cook and others, “Crack cocaine, disease progression, and mortality in a multicenter cohort of HIV-1 positive

women”, AIDS, vol. 22, No. 11 (2008), pp. 1355-1363

Barriers to an enhancing

envirionment

• PWHIV who smoke cocaine have been shown to

be less likely than their non-cocaine-smoking

peers to access medical services and are more

likely to have lower rates of ART adherence[1]

There are barriers that impede the promotion of

an enhancing environment to increase utilisation

of services. The main challenge has been the

provision of HIV and other health care services

to a highly criminalised, demonised, stigmatised

and discriminated population.

[1] M. K. Baum and others, “Crack-cocaine use accelerates HIV disease progression in a cohort of

HIV-positive drug users”, Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, vol. 50, No. 1

(2009), pp. 93-99

Amphetamine-type stimulants

(ATS)

• The use of ATS has been reported to

facilitate particular sexual behaviours and

males have reported that it enhances

sexual stamina. Smoking is a common

route of administration[1].

•

[1] Australia, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, National Drug and Alcohol Research

Centre: 2007 Annual Report (Sydney, University of New South Wales, 2007). Available from

http://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/sites/ndarc.cms.med.unsw.edu.au/files/ndarc/resources/2007%2BA

NNUAL%2BREPORT.pdf

Methamphetamine use and HIV

• Methamphetamine use has been shown to

significantly elevate the biological vulnerability to

HIV infection[1] and increase HIV disease

progression[2],[3] in men who have sex with

men. These biological vulnerabilities are more

than likely generalisable to all humans who use

stimulants.

[1] M. W. Plankey and others, “The relationship between methamphetamine and popper use and risk

of HIV seroconversion in the multicenter AIDS cohort study”, Journal of Acquired Immune

Deficiency Syndromes, vol. 45, No. 1 (2007), pp. 85-92

[2] L. Chang and others, “Additive effects of HIV and chronic methamphetamine use on brain

metabolite abnormalities”, American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 162, No. 2 (2005), pp. 361-369

[3] M. J. Taylor and others, “Effects of human immunodeficiency virus and methamphetamine on

cerebral metabolites measured with magnetic resonance spectroscopy”, Journal of NeuroVirology,

vol. 13, No. 2 (2007), pp. 150-159

Core interventions

• A comprehensive package of efficacious

interventions for HIV prevention, treatment

and care among stimulant users (who are

mostly non-injecting) include:

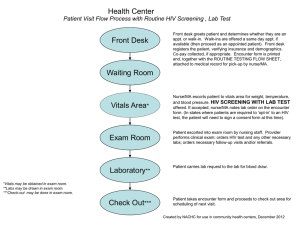

1. HIV testing and counselling

• More than 60 per cent of people living with

HIV worldwide are unaware of their HIV

status

[1].

•

1] Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, UNAIDS World AIDS Day Report 2011 (Geneva, 2011).

Available from

www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/JC2216_WorldAIDSday_report

_2011_en.pdf

2. Antiretroviral therapy (ART)

• PWHIV cocaine users have been shown to

have accelerated HIV disease

progression[1] and mortality[2], yet the

immune-enhancing effects of consistent

ART adherence are far greater than

negative immune effects caused by

stimulant use[3],[4].

•

•

•

•

[1] Baum (2009)

[2] Cook (2008)

[3] Ellis 2003

[4] S. Shoptaw and others, “Cumulative exposure to stimulants and immune function outcomes

among and HIV-negative men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study”, International Journal of STD

& AIDS, vol. 23, No. 8 (2012), pp. 576-80

High incidence environment

• stimulant users are a group may benefit

disproportionately from combination HIV

prevention strategies by reducing the pool

of PWHIV with high viral load in their

sexual networks

3 NSP for people who inject

stimulants

• Programmes whose objective is to reduce the

frequency of injecting by the provision of opioid

assisted therapy present an imperceptible yet

none the less, tangible barrier for people who

use stimulants

• No accepted substitution programme for

stimulants

• The trajectory of an NSP/OST programme that

supports the transit of people from injecting to

orally administered OST leaves stimulant users

with no comparable, accepted substitute and this

may create a barrier to integration in the

programme.

4. Harm reduction services

•

•

Harm reduction services targeting

stimulant use and other evidence-based

drug dependence treatment.

While drug dependence treatment

opportunities may be a welcome respite

from heavy episodic stimulant use,

abstinence based drug treatment has

been shown to be ineffective in

addressing HIV transmission among

the population of stimulant users

NIDU harm reduction

• Stimulant use in highly criminalised

environments face is associated with poverty,

unemployment, unstable housing and

incarceration.

• Programmes that address these issues and offer

meals, shower facilities, housing, legal

assistance and other basic services may help

stimulant users in need to stabilise their living

situation, which can increase their access to

services related to HIV and other co-morbidities,

improve adherence to medication schedules and

help them maintain ongoing HIV care

Pharmacotherapies

• Pharmacotherapies or as some say substitution therapy

(agonist pharmacotherapy, agonist replacement therapy,

agonist-assisted therapy) is defined as the administration

under medical supervision of a prescribed psychoactive

substance, pharmacologically related to the one

producing dependence, to people with substance

dependence, for achieving defined treatment aims.

Substitution therapy is widely used in the management

opioid dependence (methadone, buprenorphine)[1]

•

[1] Substitution maintenance therapy in the management of opioid dependence and HIV/AIDS prevention: position

paper / World Health Organization, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, UNAIDS.

Substitutution therapy

• Positive outcomes using sustained-release

dextroamphetamine and

dextroamphetamine as a

pharmacotherapy for amphetamines and

cocaine respectively have been reported.

The studies reported no adverse reactions

and recommended further studies be

conducted.

Cannabis

• Cannabis has also shown promise as a

therapeutic alternative to crack cocaine use.

More research needs to be conducted in this

area but service providers should note that

cannabis use should be considered therapeutic

and for those individuals who turn to cannabis

use should not be discouraged. There are no

know negative interactions between cannabis

and ART and cannabis use has been shown to

inhibit viral progression of HIV in treatment naïve

PWHIV[1].

•

[1] Costantino CM, Gupta A, Yewdall AW, Dale BM, Devi LA, et al. (2012) Cannabinoid Receptor

2-Mediated Attenuation of CXCR4-Tropic HIV Infection in Primary CD4+ T Cells. PLoS ONE 7(3):

e33961. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033961

Pharmacotherapies criteria

WHO, Drug Substitution Project, Geneva, May 1995

The following criteria should be considered essential

for a drug to be appropriate for pharmacotherapies

• It shows cross-tolerance and cross dependence

with the psychoactive substance being used.

• It reduces craving and suppresses withdrawal

symptoms.

• It facilitates psychosocial functioning and improved

health.

• It has no short or long term toxic effects.

• Affordable and available

• Does not grossly impair psychomotor functioning

HIV, stimulants and co-morbidity

• A subgroup of people who use stimulants are those with

co-morbid psychiatric conditions[1],[2],[3], yet harm

reduction services or HIV services that integrate

psychiatric care are not common.

• There is a disproportionate representation of co-morbid

psychiatric conditions in the homeless population in

many places of the world. When setting targets for

homeless populations it is important to consider the

special nature and challenge of this sub group of people

who use stimulants, have a co-morbid psychiatric

condition and are homeless.

•

•

•

[1] Lopez-Quintero and others, “Probability and predictors of transition from first use to

dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic

Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC)”, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 115,

Nos. 1-2 (2011), pp. 120-130

[2] M. J. Smith and others, “Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in substance users: a comparison

across substances”, Comprehensive Psychiatry, vol. 50, No. 3 (2009), pp. 245-250

[3] L. Degenhardt and W. Hall, “Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to

the global burden of disease”, Lancet, vol. 379, No. 9810 (2012), pp. 55-70

5. Condoms

Condom programmes for people who use

stimulants and for their sexual partners

For individuals who have used stimulants and

have reported an increased libido the

availability of condoms is critical in addressing

sexual transmission of HIV. This is especially

critical for individuals who engage in sex work,

who are very sexual active with multiple

partners, men who have sex with men, young

people, women, and the sexual partners of

stimulant users.

Capturing “condom failure”

• Most new HIV in people who use stimulants are

sexual,

• Capturing information on “condom failure” is

important. Recent unpublished data from an

internet based survey of Caribbean men who

have sex with men revealed that 27% of the

respondents reported a condom failure in the

last year[1].

•

[1] CARIMIS 2013

STI Screening

•

Screening, prevention and treatment of

STIs, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and

tuberculosis (TB)

6. Screening

•

•

Screening, prevention and treatment of

STIs, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and

tuberculosis (TB)

Screening for infectious diseases such

as sexually transmitted infections,

hepatitis B and C, and TB at the point of

contact is feasible and acceptable.

7. Behavioural interventions aimed

at reducing the risk of HIV

transmission

• No study has shown reductions of HIV

transmissions or reductions in sexual risk

behaviours that correspond with

reductions in stimulant use. Behavioural

treatments may or may not be effective in

reducing stimulant consumption but should

not be relied upon to reduce HIV

transmission.

Targeted IEC

•

Targeted information, education and

communication programmes delivered at the

community level can act as a structural

prevention intervention to increase awareness

of links between stimulant use and HIV and

promote positive behaviour change such as

HIV testing, condom use and other safer sex

practices and can provide useful information

about HIV and harm reduction appropriate to

people who use stimulants.

Factors to consider when planning,

implementing and evaluating HIV

interventions

Stimulant switching

• People who use stimulants exhibit certain

preferences for specific psycho-stimulants.

The proximity of a diverse drug market

that offers a wide range of stimulant

choices will facilitate an environment

conducive to “stimulant switching”[1].

•

[1] World Drug Report 2012

“Polydrug” use

• Due to its ease of availability, alcohol

consumption is obtainable to those who wish to

use it concurrently with their stimulants.

• Each type of polydrug use may present unique

challenges to developing specific interventions

that address the myriad of factors that result

from substance mixing.

• Factors that affect preference include “halflives”. Cocaine and crack have short half-lives

(30-45 minutes for powder cocaine; 2-10

minutes for crack); compared with ATS (9-12

hours for amphetamine and methamphetamine;

4-5 hours for ecstasy).

People who inject stimulants

• Given the “half life” issues as discussed, some

people who inject stimulant such as cocaine or

ATS may inject more often than a person who is

injecting opioids and require more sterile

syringes than the service user who injects

opioids exclusively. In order to serve the needs

of this sub group of people who inject drugs it is

important for sterile syringe programmes to

adapt the information and education they

provide to emphasize the need for safe injecting

and safe sexual practices.

Sexual risk behaviours

concomitant to stimulant use

• Stimulant use has been shown to increase

frequency of sexual intercourse and thereby

increasing the vulnerability to HIV

• Stimulant-associated unprotected sex in the

context of concurrent sexual partnerships

increase the probability of HIV transmission

• Stimulant use reduces inhibitions sufficiently to

facilitate sex work, to promote sexual exploration

and/or to overcome feelings of stigma and

internalized homonegativity

Women

• Women who use stimulants face additional and unique

challenges. One of the main challenges is the crosscultural stigma associated with their vacating gender

roles such as caring for their family and being pregnant

or mothers of infants and children

• Women face power dynamics in relationships and higher

rates of poverty; those factors interfere with their ability

to access reproductive health supplies, including

condoms and other contraceptives. Such situations are

particularly common among women who use drugs.

Women who use stimulants have elevated risks for HIV

transmission, STI, and high rates of partner violence.

Thank you