VisualCriminologyASC

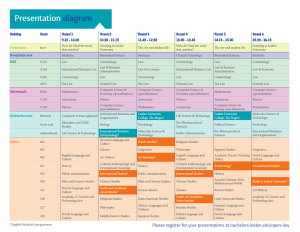

advertisement

The Rise of Visual Criminology: Categories, Approaches, and Testable Propositions J. Wheeldon Norwich University D. Harris San Jose State University Today Why visualize? Who’s visualizing? Categories and Approaches Problems Testable Propositions Why Visualize? Assumption: use of and interest in visual means and methods growing in many disciplines (Umoquit, Tso, Burchett, & Dobrow, 2012); Recognition that people are spending an increasing amount of time staring at screens, and engaging visually with their phones, computers, and social media; ahem. Who’s Visualizing? Criminologists including Burruss (2011), Heidt (2008), Lippens (2004), and Maltz (2009)? New Directions in Visual Criminology panel at ASC; This work is based on previous work (Harris, 2013; Wheeldon, 2011) and desire to better define and operationalize what we mean... One take: Visual criminology: Techniques for the collection, presentation, and interrogation of data on crime and social control (Wheeldon & Harris, 2013). Existing categories: 1) exploring research methods through expanded uses of concept maps, mind maps, and other diagrammatic approaches in criminology (Wheeldon & Ahlberg, 2012); 2) describing data, telling stories, and presenting information using visual analytic approaches (Harris, 2013; Maltz, 2009); and 3) demystifying theory, challenging research assumptions, and interrogating depictions of crime and social control (Lippens, 2012). investigations. Glenn Firebaugh (2008) summarizes seven principles for good science research. These include the possibility of surprise, the need to explore Learning Research Methods within your research, the need to compare findings of one group with findings (Wheeldon & Ahlberg, 2012) another, and to focus on how, why, and to what extent things change. Figure 1.1 Seven Rules for Social Science Research How do the differences between concept maps and mind maps underscore epistemological, assumptive, and practical differences between quantitative and qualitative research? Build in reality checks Possibility of surprise Compare like with like Seven Rules Differences matter Replicate where possible Method as a means Count change/ Change counts Existing categories: 1) exploring research methods through expanded uses of concept maps, mind maps, and other diagrammatic approaches in criminology (Wheeldon & Ahlberg, 2012); 2) describing data, telling stories, and presenting information using visual analytic approaches (Harris, 2013; Maltz, 2009); and 3) demystifying theory, challenging research assumptions, and interrogating depictions of crime and social control (Lippens, 2012). Describing Data: In SF Crime doesn’t Climb (Wintrob &Reinhardt, 2013) Crime and Neighborhoods in DC Describing Data: Most Violent Police Beats in Oakland CA 2011/2012 (Natesh Daniel, 2012) Existing categories: 1) exploring research methods through expanded uses of concept maps, mind maps, and other diagrammatic approaches in criminology (Wheeldon & Ahlberg, 2012); 2) describing data, telling stories, and presenting information using visual analytic approaches (Harris, 2013; Maltz, 2009); and 3) demystifying theory, challenging research assumptions, and interrogating depictions of crime and social control (Lippens, 2012). Depictions of Crime and Criminals Images of Crime/Criminals: Last Suppers (Green, 2012) So What? New Visual Approaches... (1) can provide new ways to teach theory, methods, and critical debates in criminology; (2) offer novel approaches to data collection and analysis; and (3) create potential for the increased use of visual tools for practitioners within the criminal justice system. Teaching Criminology Theory (Heidt & Wheeldon, Contract) 7 steps of criminological thinking Visual Data Collection Life History Plot (Harris, 2013) Data Visualization technique Official criminal history Life history details (including marriage, divorce, employment, military, births/deaths, trauma/ accidents, hospital stays, and psychiatric observations) were collected Life History Plot - Step 1 Life History Plot - Step 2 Life History Plot - Step 3 An Example from Incarcerated Individual A Picture is Worth a Thousand P- values Problems / Limitations Images can confuse and fail to clarify; Visual learning not for everyone; No clear definition / conceptualization / testable propositions Confusing not clarifying NYTimes, April 29, 2007 Mapping not for everyone Potential for maps contains inherent limitation; Maps and Visual approaches are weird / different / uncommon way for many to communicate - people may reject without proper training / explanation (Wheeldon, 2012) While maps can assist to break out of the “canned responses” that can occur in interviews in Wheeldon’s work some senior CJ officials were skeptical / resistant to their use; Thinking about testable propositions CATEGORY CHALLENGE PROPOSITION Collection Not everyone is able to communicate or engage visually Visual data collection is as good as other forms of participant-led data collection techniques “Looking at the data” first can amount to a fishing expedition (cheating) Preliminary analysis using visualization enables the identification of outliers that warrant exclusion or further study Analysis Presentation Reducing criminology to a The presentation of criminological series of “pictures” simplifies findings using visual approaches complex issues / allows more people to access and relationships / findings understand research Some Questions 1. WHAT are the best uses of visual techniques for teaching and learning criminological concepts? 2. WHERE are visual approaches most useful to supplement existing data collection methods and research designs; 3. WHEN do images oversimplify issues instead of expanding criminological thinking? 4. WHY do images of crime and social control overwhelm more reasoned approaches to criminal justice? 5. HOW can visual approaches expand partnerships and broaden collaborations? Other Questions? Johannes Wheeldon (jwheeldo@norwich.edu) Danielle Harris (danielle.harris@sjsu.edu)