InfoLit_Step7slides - The Institute for Research and Innovation in

advertisement

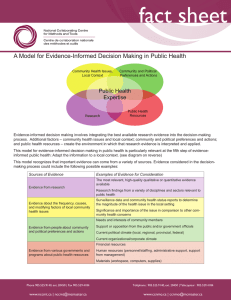

Information Literacy Step 7: Apply Apply • How will you apply the information you’ve discovered to your practice? • The skills described by the 7 steps in the information literacy cycle can help you to find research and evidence. It is important to remember, as highlighted in this unit, that the purpose of finding research and evidence is to apply it to inform practice. Learning outcomes This unit aims to support you to develop skills associated with the Apply step of the information literacy cycle. It will enable you to: • identify barriers and enablers to using research in practice; • assess the relevance of research before applying it to practice; • identify the strengths and weaknesses of three different practice models for getting research into practice. What do we mean by evidence-informed practice? Evidence-informed practice means that decisions about how to meet the needs of service users are informed by and understanding of: • • • the best available evidence about what is effective practice wisdom (the fruits of operational experience) the views of service users (e.g. about expectations, preferences or the impact of their problems and our interventions) *Extracted from Hodson, R. & Cooke, E. (2007). Leading Evidence-Informed Practice: a handbook. Research in Practice. ©research in practice 2007. Being ‘evidence informed’ • Evidence about what is effective comes from research – from large-scale academic studies as well as from data gathered systematically by social care agencies (e.g. from local user consultations or service evaluations). • Being ‘evidence-informed’ in your work implies a number of things: – asking challenging questions about current practice – knowing how and where to find relevant research – understanding key messages about what works *Extracted from Hodson, R. & Cooke, E. (2007). Leading Evidence-Informed Practice: a handbook. Research in Practice. ©research in practice 2007. Barriers to using research in practice • Culture: social services workers operate in a predominantly verbal culture & show a strong preference for face to face communication (Harrison et al., 2004; Gannon-Leary, 2006). • Time: heavy workloads & staff shortages = time pressure & find it difficult to find time to search for, evaluate and apply published research findings (Booth et al., 2003; Sheldon et al., 2005). • Low priority: related to time pressures and workloads, practitioners struggle to prioritise research over the more immediate demands of practice (Walter et al., 2003). • Poor communication of research within organisations (Walter et al., 2003). • Research is not timely or relevant to user’s needs. (Walter et al., 2003). • Skills: Lack of IT skills and information literacy skills. • Access: Technical issues e.g. access to the Internet (e.g. Blackburn, 2001; Harrison et al., 2004; Gannon-Leary, 2006; Booth et al., 2003; Moseley, 2004). Sharing of PCs between workers, low bandwidth and restrictive firewalls make access to online resources problematic. Where technical access is possible, access to research evidence itself may not be. SSKS has addressed some of these… • Access: SSKS provides free access to a huge library of quality information and research for the social services • Skills training: SSKS provides a training pack, a unit on each step of the information literacy cycle, to help staff develop skills to support them to find and use evidence in their practice. Enablers to using research in practice Practices that support & promote research in practice… • Ensuring a relevant research base: research needs to be relevant to local needs. • Ensuring access to research: improved access to library services, the Internet and research databases are important. • Making research comprehensible: Summaries and other user-friendly formats that communicate key messages of research can promote research. • Drawing out practice implications of research: defining the implications of research for day-to-day practice and demonstrating how these can be applied in local and national contexts is important. • Developing best practice models: pilot and demonstration projects that are based on research findings directly integrate research into practice. • Requiring research-informed practice: making research a requirement - by, for example, building it into service design and practice supervision - will increase its use. • Developing a culture that supports research use: the inclusion of research use into the curriculum of staff training and development and in national policy statements as well as research champions at local level. * Summarised from: Walter, I., Nutley, S., Percy-Smith, J., Frost, S. (2004). Improving the use of research in social care practice, Knowledge Review, 7. Social Care Institute for Excellence, London. Activity 1 • What do you think the barriers are to using research in your work context? • Can you think of enablers that could address these barriers? How relevant is the research to your own practice? • Who are the service users? (e.g. think about age, ethnicity, gender, family relationships) • What are the issues or conditions involved? (e.g. learning disability, mental health problems) • What interventions are involved? • What were the outcomes? • How does your practice context compare to the context of the research? (e.g. think about policy and legislative differences, environmental differences, range of professionals involved) • Can you act on the evidence? Do you have the skills and confidence to change your practice in light of the research? * Adapted from: Frost, S. et al. (2006). The evidence guide: using research and evaluation in social care and allied professions. Barnardo’s / What Works for Children? / Centre for Evidence-Based Social Services. GETTING RESEARCH INTO PRACTICE: Three models for developing research-informed practice (Walter et al., 2004) Research-based practitioner model 1. The research-based practitioner model is based on the idea that: • It is the role and responsibility of individual practitioners to keep up-to-date with and apply research. • The use of research is a linear process - access, appraise, apply. • Practitioners have professional autonomy – in other words, practitioners are able to change their practice based on research as they see fit. • Professional education and training are important to enable research use. Embedded research model 2. The embedded research model is based on the idea that: • Research use is achieved by embedding research in systems and processes - standards, policies, procedures and tools. • Research use is seen as linear and instrumental – research is translated directly into practice change. • The responsibility for research use lies with policy makers and managers. • Performance management and regulatory regimes encourage the use of research based guidance and tools. Organisational excellence model 3. The organisational excellence model is based on the idea that: • The key to successful research use rests with social care delivery organisations: their leadership, management and organisation. • Research findings are adapted to local settings and ongoing learning is encouraged within organisations. • Research use is supported and promoted by developing a “research-minded” local culture. • Partnerships with local universities and intermediary organisations are used to facilitate the creation and use of research knowledge. Activity 2 • In pairs or as a group, discuss the 3 models for developing research-informed practice and describe the advantages and disadvantage of each one. • Which do you think might be most effective and why? References • Blackburn, N. (2001). Building bridges: Toward integrated library and information services for mental health and social care. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 18 (4), 203-121. • Booth, S., Booth, A., & Falzon, L. (2003). The need for information and research skills training to support evidence-based social care: A literature review and survey. Learning in Health and Social Care, 2(4), 191-201. • Frost, S., Moseley, A., Tierney, S., Hutton, A., Ellis, A., Duffy, M. and Newman, T., with Scott, S. and Pettitt, B. (2006). The evidence guide: using research and evaluation in social care and allied professions. Barnardo’s / What Works for Children? / Centre for Evidence-Based Social Services. • Gannon-Leary, P. (2006). Glut of information, dearth of knowledge? A consideration of the information needs of practitioners identified during the FAME project. Library Review, 55(2), 120-131. • Harrison, J., Hepworth, M., & De Chazal, P. (2004). NHS and social care interface: A study of social workers' library and information needs. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 36(1), 27-36. • Hodson, R., & Cooke, E. (2007). Leading Evidence-Informed Practice: a handbook. Research in Practice. • Moseley, A. (2004). The Internet: Can you get away without it? Supporting the caring professions in accessing research for practice. Journal of Integrated Care, 12(3), 30-37. • Sheldon, B., Chilvers, R., Ellis, A., Moseley, A. and Tierney, S. (2005) 'A pre-post empirical study of obstacles to, and opportunities for, evidence-based practice in social care', in Bilson, A. (ed), Evidence-based practice in social work, London: Whiting & Birch Ltd. • Walter, I., Nutley, S., Davies, H. (2003). Research impact: a cross sector literature review. Research Unit for Research Utilisation, University of St. Andrews. • Walter, I., Nutley, S., Percy-Smith, J., Frost, S. (2004). Improving the use of research in social care practice, Knowledge Review, 7. Social Care Institute for Excellence, London. Further reading • Making Research Count: http://www.beds.ac.uk/research/iasr/mrc • Research in Practice: http://www.rip.org.uk/ • Research in Practice for Adults: http://www.ripfa.org.uk/ • What works for Children?: http://www.whatworksforchildren.org.uk/ Copyright & Credits (c) 2009 Institute for Research and Innovation in Social Services except where indicated otherwise. This work is based on and derived from Better informed for better health and better care. NHS Education Scotland, 2009 (http://www.infoliteracy.scot.nhs.uk/information-literacy-framework.aspx). CC-BY-NC. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.5 UK : Scotland License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/scotland/. This means that, unless indicated otherwise, you may freely copy and adapt this work provided you acknowledge IRISS as the source. Specifically: * The Information Literacy Cycle diagram may be copied but may not be modified without permission from NHS Education Scotland [contact: Eilean.Craig@nes.scot.nhs.uk] * The article reproduced with the permission of the Press Association may not be included in any derivative work.