PowerPoint Presentation - University of Sheffield

advertisement

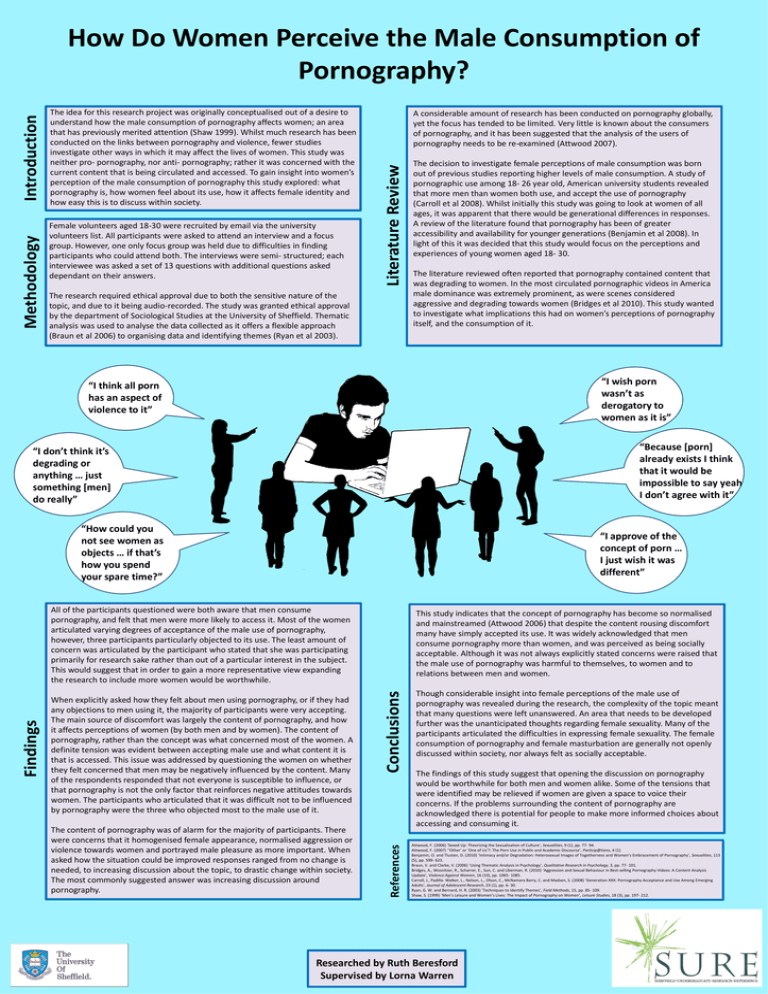

The idea for this research project was originally conceptualised out of a desire to understand how the male consumption of pornography affects women; an area that has previously merited attention (Shaw 1999). Whilst much research has been conducted on the links between pornography and violence, fewer studies investigate other ways in which it may affect the lives of women. This study was neither pro- pornography, nor anti- pornography; rather it was concerned with the current content that is being circulated and accessed. To gain insight into women’s perception of the male consumption of pornography this study explored: what pornography is, how women feel about its use, how it affects female identity and how easy this is to discuss within society. Female volunteers aged 18-30 were recruited by email via the university volunteers list. All participants were asked to attend an interview and a focus group. However, one only focus group was held due to difficulties in finding participants who could attend both. The interviews were semi- structured; each interviewee was asked a set of 13 questions with additional questions asked dependant on their answers. A considerable amount of research has been conducted on pornography globally, yet the focus has tended to be limited. Very little is known about the consumers of pornography, and it has been suggested that the analysis of the users of pornography needs to be re-examined (Attwood 2007). Literature Review Methodology Introduction How Do Women Perceive the Male Consumption of Pornography? The research required ethical approval due to both the sensitive nature of the topic, and due to it being audio-recorded. The study was granted ethical approval by the department of Sociological Studies at the University of Sheffield. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data collected as it offers a flexible approach (Braun et al 2006) to organising data and identifying themes (Ryan et al 2003). The decision to investigate female perceptions of male consumption was born out of previous studies reporting higher levels of male consumption. A study of pornographic use among 18- 26 year old, American university students revealed that more men than women both use, and accept the use of pornography (Carroll et al 2008). Whilst initially this study was going to look at women of all ages, it was apparent that there would be generational differences in responses. A review of the literature found that pornography has been of greater accessibility and availability for younger generations (Benjamin et al 2008). In light of this it was decided that this study would focus on the perceptions and experiences of young women aged 18- 30. The literature reviewed often reported that pornography contained content that was degrading to women. In the most circulated pornographic videos in America male dominance was extremely prominent, as were scenes considered aggressive and degrading towards women (Bridges et al 2010). This study wanted to investigate what implications this had on women’s perceptions of pornography itself, and the consumption of it. “I wish porn wasn’t as derogatory to women as it is” “I think all porn has an aspect of violence to it” “Because [porn] already exists I think that it would be impossible to say yeah I don’t agree with it” “I don’t think it’s degrading or anything … just something [men] do really” “How could you not see women as objects … if that’s how you spend your spare time?” “I approve of the concept of porn … I just wish it was different” The content of pornography was of alarm for the majority of participants. There were concerns that it homogenised female appearance, normalised aggression or violence towards women and portrayed male pleasure as more important. When asked how the situation could be improved responses ranged from no change is needed, to increasing discussion about the topic, to drastic change within society. The most commonly suggested answer was increasing discussion around pornography. Conclusions When explicitly asked how they felt about men using pornography, or if they had any objections to men using it, the majority of participants were very accepting. The main source of discomfort was largely the content of pornography, and how it affects perceptions of women (by both men and by women). The content of pornography, rather than the concept was what concerned most of the women. A definite tension was evident between accepting male use and what content it is that is accessed. This issue was addressed by questioning the women on whether they felt concerned that men may be negatively influenced by the content. Many of the respondents responded that not everyone is susceptible to influence, or that pornography is not the only factor that reinforces negative attitudes towards women. The participants who articulated that it was difficult not to be influenced by pornography were the three who objected most to the male use of it. This study indicates that the concept of pornography has become so normalised and mainstreamed (Attwood 2006) that despite the content rousing discomfort many have simply accepted its use. It was widely acknowledged that men consume pornography more than women, and was perceived as being socially acceptable. Although it was not always explicitly stated concerns were raised that the male use of pornography was harmful to themselves, to women and to relations between men and women. References Findings All of the participants questioned were both aware that men consume pornography, and felt that men were more likely to access it. Most of the women articulated varying degrees of acceptance of the male use of pornography, however, three participants particularly objected to its use. The least amount of concern was articulated by the participant who stated that she was participating primarily for research sake rather than out of a particular interest in the subject. This would suggest that in order to gain a more representative view expanding the research to include more women would be worthwhile. Though considerable insight into female perceptions of the male use of pornography was revealed during the research, the complexity of the topic meant that many questions were left unanswered. An area that needs to be developed further was the unanticipated thoughts regarding female sexuality. Many of the participants articulated the difficulties in expressing female sexuality. The female consumption of pornography and female masturbation are generally not openly discussed within society, nor always felt as socially acceptable. The findings of this study suggest that opening the discussion on pornography would be worthwhile for both men and women alike. Some of the tensions that were identified may be relieved if women are given a space to voice their concerns. If the problems surrounding the content of pornography are acknowledged there is potential for people to make more informed choices about accessing and consuming it. Attwood, F. (2006) ‘Sexed Up: Theorizing the Sexualisation of Culture’, Sexualities, 9 (1), pp. 77- 94. Attwood, F. (2007) ‘‘Other’ or ‘One of Us’?: The Porn Use in Public and Academic Discourse’, Particip@tions, 4 (1). Benjamin, O. and Tlusten, D. (2010) ‘Intimacy and/or Degradation: Heterosexual Images of Togetherness and Women’s Embracement of Pornography’, Sexualities, 113 (5), pp. 599- 623. Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) ‘Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, pp. 77- 101. Bridges, A., Wosnitzer, R., Scharrer, E., Sun, C. and Liberman, R. (2010) ‘Aggression and Sexual Behaviour in Best-selling Pornography Videos: A Content Analysis Update’, Violence Against Women, 16 (10), pp. 1065- 1085. Carroll, J., Padilla- Walker, L., Nelson, L., Olson, C., McNamara Barry, C. and Madsen, S. (2008) ‘Generation XXX: Pornography Acceptance and Use Among Emerging Adults’, Journal of Adolescent Research, 23 (1), pp. 6- 30. Ryan, G. W. and Bernard, H. R. (2003) ‘Techniques to Identify Themes’, Field Methods, 15, pp. 85- 109. Shaw, S. (1999) ‘Men’s Leisure and Women’s Lives: The Impact of Pornography on Women’, Leisure Studies, 18 (3), pp. 197- 212. Researched by Ruth Beresford Supervised by Lorna Warren