Treatment of Eating Disorders

advertisement

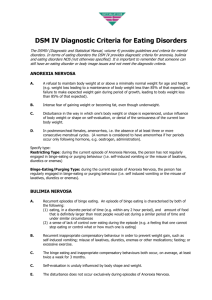

Dr Jackie Hoare Liaison Psychiatry GSH is an illness characterised by extreme concern about body weight with serious disturbances in eating behavior leading to a self-imposed starvation state Severe weight loss. Body image becomes the predominant measure of selfworth denial of the seriousness of the illness. (a) refusal to maintain weight within the normal range for height and age (b) fear of weight gain; (c) body image disturbance (d) absence of menstrual cycles or amenorrhea in women (and loss of sexual interest in men). Criterion A focuses on behaviors, like restricting calorie intake But no longer includes the word ‘refusal’ in terms of weight maintenance since that implies intention on the part of the patient The DSM-IV Criterion requiring amenorrhea, is deleted. This criterion cannot be applied to males, children, OC, and post-menopausal females. exhibit all other symptoms and signs of anorexia nervosa but still report some menstrual activity All 3 of the following: Energy restriction leading to significantly low body weight Fear of weight gain or behavior interfering with weight gain Disturbance in self perceived weight or shape Restricting type Binge eating /purging type; recurrent episodes of bingeing or purging in the last 3 months Mild BMI>17 kg/m2 Moderate 16-16.9 Severe 15-15.9 Extreme <15 Few controlled trials to guide treatment Weight restoration, family therapy and structured psychotherapy Improve nutritional health – refeeding Drugs can be used to treat co-morbid conditions Limited role in weight restoration Phosphate, K+, thiamine, Mg, Ca2+ supplementation in oral form results in a decrease in the serum levels of phosphate, potassium, and magnesium, all of which are already depleted. hormonal and metabolic changes are aimed at preventing protein and muscle breakdown. use fatty acids as the main energy source. increase in blood levels of ketone bodies brain to switch from glucose to ketone bodies as its main energy source. The liver decreases its rate of gluconeogenesis, thus preserving muscle protein. several intracellular minerals become severely depleted serum concentrations of these minerals (including phosphate) may remain normal. reduction in renal excretion. During refeeding, glycaemia leads to increased insulin and decreased secretion of glucagon. Insulin stimulates glycogen, fat, and protein synthesis. Insulin stimulates the absorption of potassium into the cells through the sodium-potassium ATPase symporter, which also transports glucose into the cells. Magnesium and phosphate are also taken up into the cells. Water follows by osmosis. These processes result in a decrease in the serum levels of phosphate, potassium, and magnesium The clinical features of the refeeding syndrome occur as a result of the functional deficits of these electrolytes and the rapid change in basal metabolic rate. rate of feeding should be slowed down and essential electrolytes should be replenished. Fluid repletion should be carefully controlled to avoid fluid overload Bone loss complication serious consequences Hormonal treatment with oestrogen or dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) no positive effect on bone density Oestrogen not recommended in children and adolescents – risk premature fusion of bones 2009 Cochrane review: no evidence from 4 placebo controlled trials On weight gain, eating disorder or associated psychopathology Suggested neurochemical abnormalities in starvation may explain non-response Co-prescribing supplementation incl. tryptophan with fluoxetine does not increase efficacy Olanzapine, benzodiazepines or promethazine to reduce anxiety with refeeding 1 RCT showed 88% of patients given olanzapine achieved weight restoration (55% placebo) Quetiapine may improve psychological symptoms but few data Small trial suggested that fluoxetine useful in improving outcome and preventing relapse after weight restoration Other studies found no benefit Antidepressants often used to treat co-morbid depression and OCD However these conditions may resolve with weight gain alone Significant disturbance in eating manifested by persistent failure to meet nutritional/energy requirement associated with 1 of: Significant weight loss Significant nutritional deficiency Dependence on enteral feeding or supplements Interference with psychosocial functioning NOT due to lack of food or body image disturbance Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) has replaced Feeding Disorder of Infancy and Early Childhood and EDNOS which was described in the DSM-IV. While few data on ARFID have been published, it appears that it usually presents in infancy or childhood, but it can also present or persist into adulthood. The course of illness for individuals relatively unknown. Avoidance due to sensory characteristics of food, emotional difficulties, food beliefs etc. ARFID may be associated with impaired social functioning and affect family functioning, especially if there is great stress surrounding mealtimes. The presence of other psychological disorders may be risk factors for ARFID, such as anxiety disorders, obsessivecompulsive disorders, attention deficit disorders, and autism spectrum disorders If an individual presents with one of these illnesses and an eating problem, a diagnosis of ARFID should be given only when the feeding disturbance itself is causing significant clinical impairment individuals with a history of gastrointestinal conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux may develop feeding disturbances, but a diagnosis of ARFID should be assigned only when the feeding disturbances require significant treatment beyond that needed for the gastrointestinal problems. Little is currently known about effective treatment interventions for individuals presenting with ARFID given the prominent avoidance behaviors, it seems likely that behavioral interventions, such as forms of exposure therapy depression or anxiety that affects feeding, cognitive behavioral therapy and other treatments for the underlying condition Bulimia nervosa is characterized by recurrent and frequent episodes of eating unusually large amounts of food feeling a lack of control over the eating. purging (e.g., vomiting, excessive use of laxatives or diuretics), fasting and/or excessive exercise DSM-5 criteria reduce the frequency of binge eating and compensatory behaviors to once a week from twice weekly as specified in DSM-IV. Psychological treatments first choice Adults mat be offered antidepressants SSRI’s esp fluoxetine 60mg effective dose Can reduce frequency of binge eating and purging Long term effects unknown Early response at 3 weeks strong indicator of response overall Used off licensed in adolescents Some evidence for topiramate, duloxetine, lamotrigine and sertraline reduce binges Binge eating disorder will now have its own category as an eating disorder. In the DSM-IV, under the category Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified “recurring episodes of eating significantly more food in a short period of time than most people would eat under similar circumstances, with episodes accompanied by feelings of lack of control.” eat quickly and uncontrollably, despite hunger signals or feelings of fullness. feelings of guilt, shame, or disgust behavior will have typically taken place at least once a week over a period of three months. NICE recommends Evidenced based self help programme of CBT as first line Trial of SSRI as an alternative or additional first step Although AN is not a common condition its morbidity and mortality are amongst the highest psychiatric disorders due to malnutrition, purging behavior and suicide. 18-fold increase in mortality in patients with AN Over 7 years, the majority of women with anorexia nervosa experienced diagnostic crossover: more than half crossed between the restricting and binge eating/purging anorexia nervosa subtypes over time; one-third crossed over to bulimia nervosa but were likely to relapse into anorexia nervosa. Women with bulimia nervosa were unlikely to cross over to anorexia nervosa Key is MDT Dietician, psychology, medicine, psychiatry, OT and social worker Clearly defined case manager , roles of team members in case defined