Povinelli TOM chimpanzee studies

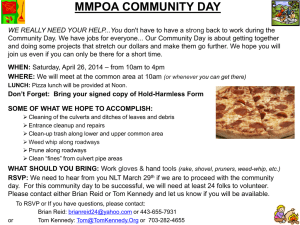

advertisement

Chapter 15: Santos, L. R., Flombaum, J. I., & Phillips, W. The evolution of human mind-reading: How nonhuman primates can inform social cognitive neuroscience (pp. 433-456) • The secret to our evolutionary success is our social intelligence and the key to our social intelligence is TOM; the ability to infer the motivations, intentions, and belief states of others. “Why is so-and-so doing x?” Neuroscience of TOM • • • • • • • • Diverse areas of brain have been implicated in variety of studies including: Visual cortex Amygdala Anterior cingulate cortex Medial frontal cortex Superior temporal sulcus Major limitation of neuroscience studies is inability to break down TOM in to elementary components and identify which parts of brain are associated with specific components of TOM For example: visual cortex probably involved in identifying self-directed action and amygdale probably involved in identifying emotional signals, but isolating this is difficult Do nonhuman primates have TOM? • Dan Povinelli: No • Brain Hare: Yes, sometimes Povinelli TOM chimpanzee studies Hare et al.’s set up Rhesus Macaques and TOM • Cayo Santiago field station in Puerto Rico. • Human experimenter approach monkey; placed a platform on the ground and put a grape on the platform. E then either faced grape or (a) turned around; (b) averted eyes; (c) blocked vision with small barrier or blocked mouth with small barrier. Rhesus TOM • Would monkeys take into account what a competitor knows based on past experience, rather than what a competitor currently sees? • E placed to grapes on platform where one could be triggered to roll to a different location. E would be “unaware” (from monkey’s perspective) of new location of rolled grape. Monkey watches. Monkeys attempt to steal grape that E did not know had moved. Behavioral- abstraction hypothesis. • • • • Alternative interpretation offered by Povinelli: Behavioral- abstraction hypothesis. Certain bodily postures are more likely to be associated with non-aggressive behaviors. Monkey or chimpanzee notes bodily position of competitor and notes likelihood of being challenged by competitor. “Competitor does not know where grape is” or “competitor is not in a position to challenge me for grape” Problem is that these two hypothesis may be indistinguishable in terms of predicting behavior. Behavioral- abstraction hypothesis • Authors argue that TOM interpretation probably wins on grounds of parsimony • BA hypo argues that monkeys and apes use correlated behavioral cues to predict future behavior, • But why are only cues directly associated with mental states used? Direction of mouth or nose are ignore but equally correlated to behavior. • If we are only using behavioral cues that constrain mental states then aren’t we really down to a TOM system? Neuroscience evidence: Superior Temporal Sulcus • In monkeys: important for registering another’s head and body position and possibly what another “sees.” • In humans: important for interpreting goals and desires • This system may be malfunctioning in autistics who have difficulty using gaze direction as an indicator of another’s goal or desire. STS and Amygdala • Amygdala may play the role of binding emotional content to another’s goal based on gaze direction. Link may occur for nonhuman primates in competitive situations but not cooperative. Could this be important evolutionary distinction between human and nonhuman primates?