The Classical Concerto

advertisement

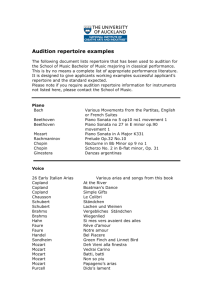

The Classical Concerto The Classical concerto (c. 1750–1830) since1750 the concerto has found its chief place in society not in church or at court but in the concert hall. Some of the excitement it could arouse in classical musical life is recaptured in the Mozart family letters. Mozart’s introduction of a new piano concerto (K. 456?) in a Vienna theatre concert was reported by his father on February 16, 1785: . . . your brother played a glorious concerto, . . . I was sitting [close] . . . and had the great pleasure of hearing so clearly all the interplay of the instruments ... (100 of 14655 words) A classical concerto is a three-movement work for an instrumental soloist and orchestra. It combines the soloist's virtuosity and interpretive abilities with the orchestra's wide range of tone colour and dynamics. Emerging from this encounter is a contrast of ideas and sound that is deamatic and satisfying. The classical love of balance can be seen in the concerto, wher soloist and orchestra are equally important. Solo instruments in classical concertos include violin, cello, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, horn and piano. Concertos can last anywhere from 20 to 45 minutes, and it has three movements: (1)fast, (2)slow, and (3)fast. A concerto has no minuet or scherzo. Int the first movement and sometimes in the last movement, there is a special unaccompanied showpiece for the soloist, the cadenza. The soloist will be able to display virtuosity by playing dazzling scale passages and broken chords. Themes of the movement are varied and presentd in new keys. At the end of a cadenza, the soloist plays a long trill followed by a chord that meshes with the re-entrance of the orchestra. Cadenzas are improvised by the soloist. Classical concertos Further information: Mozart Piano Concertos The concertos of Bach’s sons are perhaps the best links between those of the Baroque period and those of Mozart. C.P.E. Bach’s keyboard concertos contain some brilliant soloistic writing. Some of them have movements that run into one another without a break, and there are frequent cross-movement thematic references. Mozart, as a boy, made arrangements for harpsichord and orchestra of three sonata movements by Johann Christian Bach. By the time he was twenty, he was able to write concerto ritornelli that gave the orchestra admirable opportunity for asserting its character in an exposition with some five or six sharply contrasted themes, before the soloist enters to elaborate on the material. He wrote one concerto each for flute, oboe (later rearranged for flute and known as Flute Concerto No. 2), clarinet, and bassoon, four for horn, a Concerto for Flute, Harp and Orchestra, and a Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Viola and Orchestra. They all exploit the characteristics of the solo instrument brilliantly. His five violin concertos, written in quick succession, show a number of influences, notably Italian and Austrian. Several passages have leanings towards folk music, as manifested in Austrian serenades. However, it was in his twenty-three original piano concertos that he excelled himself. It is conventional to state that the first movements of concertos from the Classical period onwards follow the structure of sonata form. Mozart, however, treats sonata form in his concerto movements with so much freedom that any broad classification becomes impossible. For example, some of the themes heard in the exposition may not be heard again in subsequent sections. The piano, at its entry, may introduce entirely new material. There may even be new material in the so-called recapitulation section, which in effect becomes a free fantasia. Towards the end of the first movement, and sometimes in other movements too, there is a traditional place for an improvised cadenza. The slow movements may be based on sonata form or abridged sonata form, but some of them are romances. The finale is sometimes a rondo, or even a theme with variations. Aspects of the topic concerto are discussed in the following places at Britannica. history and development Baroque and Classical periods (in Western music: The sonata and concerto) Beethoven (in Ludwig van Beethoven (German composer): Structural innovations) Brahms (in Johannes Brahms (German composer): Aims and achievements) counterpoint (in counterpoint (music): The Baroque period) http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/213672/mu sical-form/27882/The-sonata#ref396056 “the end “