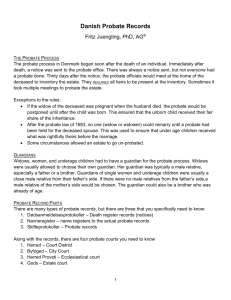

Wills, Trusts, & Estates

advertisement

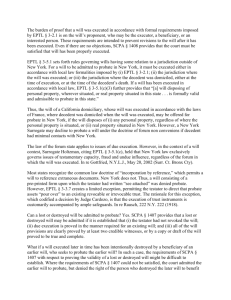

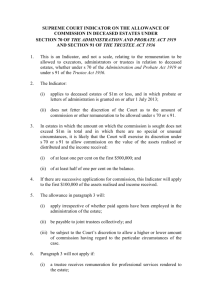

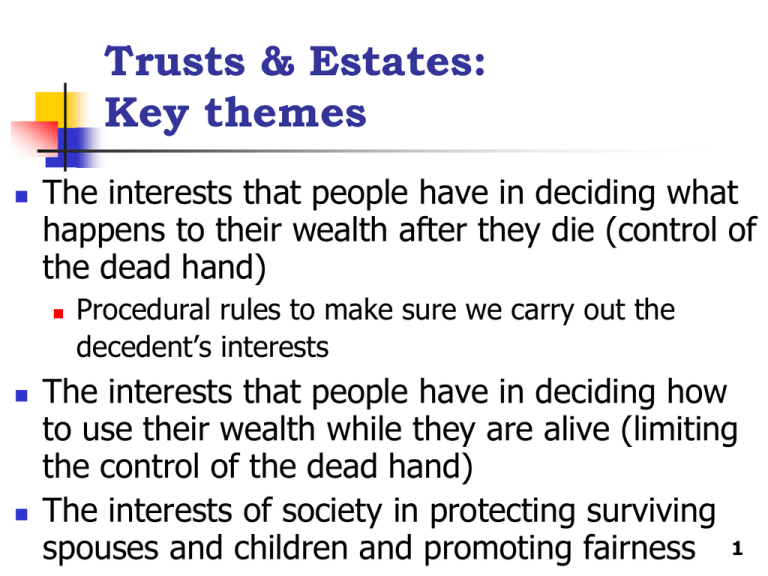

Trusts & Estates: Key themes The interests that people have in deciding what happens to their wealth after they die (control of the dead hand) Procedural rules to make sure we carry out the decedent’s interests The interests that people have in deciding how to use their wealth while they are alive (limiting the control of the dead hand) The interests of society in protecting surviving spouses and children and promoting fairness 1 Legal basis for Trusts & Estates law Is it a natural right to determine the disposition of one’s property? Or is it a privilege that has been granted by the state and that can be revoked by the state? Jefferson: People do not really own property. Rather it belongs to society, and individuals only have the right to use—and the responsibility to maintain— property during their lifetimes (p.1) Blackstone also saw it as a grant of the state (pp.1-2) 2 Legal basis for Trusts & Estates law The Supreme Court viewed the testamentary right as a privilege at first (Irving Trust, 1942) “Rights of succession to property of a deceased, whether by will or by intestacy, are of statutory creation, and the dead hand rules succession only by sufferance.” “Nothing in the Federal Constitution forbids the legislature of a state to limit, condition, or even abolish the power of testamentary disposition over property within its jurisdiction” (emphasis added) Page 3 3 Legal basis for Trusts & Estates law In 1987, the Supreme Court changed course and held that the Constitution is implicated when the government totally abolishes the right to leave one’s property to one’s chosen beneficiaries. The government may impose reasonable limits on what people may write in their wills, and estate taxes are valid However, if the government tries to take away in its entirety the right to dispose of one’s property at death, then we have a taking of private property without just compensation (5th Amendment taking) (Hodel v. Irving, page 3) 4 Did the Supreme Court finally get it right? Individuals have an important interest in providing for their children and other relatives. Allowing for inheritance promotes the responsibility of people to provide for their children and other relatives, relieving society of that obligation Allowing for wills promotes stronger family ties, and stronger families are good for society. If children know that they might inherit their parents’ wealth, they’re more likely to treat them well in their old age, as well as earlier in time. 5 Did the Supreme Court finally get it right? Allowing people to write wills Promotes hard work and productivity. Why continue to build wealth if the government claims it at your death? Promotes saving over consumption. May result in better decisions on the disposition of the wealth—individuals may make better decisions than government. 6 Did the Supreme Court finally get it right? How can the U.S. promise to be a land of opportunity, where everyone has an equal chance to succeed, when some people can inherit millions of dollars and other people inherit nothing? Inheritance allows people to enjoy “significant comforts and power they have not earned” (p. 17) Inheritance allows for the creation of an aristocratic class in this country, something that undermines the idea of a democracy (p. 18) 7 8 Did the Supreme Court finally get it right? Can we equalize opportunities by restricting dispositions at death (pp. 24-27)? People provide their children with advantages during their lifetime that may be much more important than what they leave in their wills. Parents vary in terms of Their investments in their children’s education The richness of the home environment, including health care, food and shelter, extra-curricular activities, summer camps, etc. As people are living longer, inheritances may not reach children until they already have reached their peak earning years or their retirement (Warren Buffett’s three children are over the age of 50) Estate taxes are important, but it is much more important to equalize incomes than inheritances 9 Probate and nonprobate property (p. 38) Probate Property Property that passes through probate under the decedent’s will or by intestacy. Nonprobate Property Property that passes outside of probate through a nonprobate mode of transfer (most property) Joint tenancy (real and personal) Bank accounts, mutual fund accounts, homes Life insurance Contracts with payable-on-death (POD) provisions Retirement accounts Property put in an inter vivos trust while the decedent was alive 10 Functions of probate (p. 39) The three core functions of probate: Provide evidence of transfer of title to the new owners; Protect creditors by providing a procedure for payment of debts; and Distribute the decedent’s property to those intended after the decedent’s creditors are paid. 11 Formal v. informal probate (pp. 43-44) Formal Probate The court supervises the actions of the personal representative in administering the estate through a potentially costly and time consuming process. Informal Probate The personal representative may administer the estate without court supervision unless an interested party asks for court review Interested parties include heirs, devisees, children, spouses, creditors, beneficiaries 12 Problems, pages 47-48 13